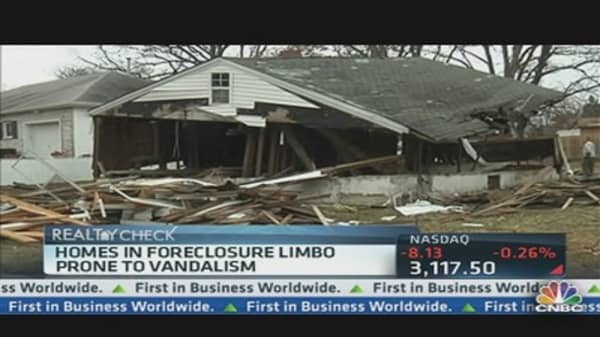

Even as the housing market accelerates on the road to recovery, there are still glaring reminders of the crash that was. Thousands of empty, foreclosed properties dot streets. A growing number of these homes, however, are not actually foreclosures. The borrowers still own them, whether they know it or not.

"This happens in what are really distressed markets," said Ed Jacob, executive director of Neighborhood Housing Services of Chicago. "What we're finding in those neighborhoods is in judicial states [where a foreclosure case has to go before a judge], banks are making a decision that it's going to take two years to complete this foreclosure, and increasingly cities are enforcing things on codes and vacant buildings. Banks are looking at what the residual values will be and then the costs they will incur and essentially saying it's not worth it for us to go through the entire foreclosure process."

Under a settlement signed early last year between state attorneys general, the U.S. Department of Justice and the nation's five largest mortgage servicers over so-called "robo-signing" foreclosure abuses, if a bank chooses not to pursue a foreclosure on a delinquent loan, it must, "notify the borrower of the Servicer's decision to release the lien and not to pursue foreclosure, and inform the borrower about his or her right to occupy the property." (Read More: Banks Pay Big for Robo-Signing…Again.)

In other words, the bank eats the mortgage, and the borrower owns the home free and clear. These rules started last October.

There are thousands of properties where banks will eventually or have released the liens, according to one bank source. The banks must send the borrower a notice of the release.

"There are people who are going to be thrilled by this, but then there are going to be the others who walked away, and the property would go back to the county," said the source. (Read More: One Overlooked Fact About the Housing Recovery .)

The trouble is, there are many borrowers who received delinquency notices or notices of default and thought they had to vacate. These were not notices of eviction or final foreclosure. Still, the borrower left before receiving the notice that the bank had walked away and extinguished the mortgage. The borrowers therefore may not know they own the home, nor do they know that they are still responsible for property taxes and upkeep. Rather than finding out that they've just been relieved of a huge debt, they discover later that they are just in more legal trouble.

"Does the bank rep think people are sophisticated enough to know the difference? They get a notice from a bank ... this is complicated stuff. They don't know if the sheriff will be out in 30 days. In some cases they probably stopped opening the letters from the bank. Some homeowners have fatigue," Jacob noted.

Other homeowners, however, have just walked away voluntarily. They don't expect to see any value in the home any time in the foreseeable future, and they're not interested in negotiating with banks for a mortgage modification. Banks are unable to find them to notify them that the lien has been released, and now cities and municipalities are left holding the bag. Eventually the homes end up in a tax foreclosure, but will likely sit empty for years.

"It's a challenge for the cities now because if they want to redevelop that property, who do they go after?" Jacob said. (Read More: Housing Recovers, but the Repo Man Is Back .)

Again, this problem is most prevalent in the nation's hardest hit neighborhoods, where home values are very low and where some properties are uninhabitable.

If a bank sees any real value in a house, they will take it to foreclosure and likely sell it to an investor. What is still unclear is timelines. How long will it take for a bank to make a decision on a potential foreclosure? While some homeowners may refuse to leave until they get an eviction notice, more will walk away if they think foreclosure is inevitable.

A homeowner who leaves the house unwillingly before an eviction notice is "unusual" according to a bank source, but it can and does happen. Whether out of confusion or expectation, the person picks up and moves, never knowing that the possibility exists that the bank will walk away and leave them owning the home free and clear. (Read More: Already Time to Throw Up Caution Signs on Housing? )

The consequences could end up costing the homeowner thousands in taxes, maintenance and utilities and leaving them open to wage garnishment and legal liability. In other words, until the sheriff kicks you out, it's probably best to stay put.

—By CNBC's Diana Olick; Follow her on Twitter @Diana_Olick or on Facebook at facebook.com/DianaOlickCNBC

Questions? Comments? RealtyCheck@cnbc.com