(Click here for the latest commodity prices.)

The CRB Index, heavily weighted with age, has also declined measurably from its recent peak.

Likewise, despite geopolitical hot spots around the world, energy prices have also dropped from recent highs. While oil remains stubbornly above $100 a barrel, both at home and abroad. Were it not for recent events in Ukraine and the Middle East, oil prices may have continued their recent dip below that century mark.

Natural gas prices have slumped to below $4 per thousand BTUs, the lowest level in months, if not years. Milder summer weather around the country, and burgeoning supplies of natural gas, have caused these prices to crash from their all-time highs. Consumers use natural gas to power their homes, from electrical power to heating and air-conditioning.

Power bills are likely to fall this summer — a boon to disposable income. Gasoline prices, on the flip side, remain stubbornly high, but could easily decline if markets sense that geopolitical risks do not escalate beyond current levels.

Even more telling is the level of interest rate and the slope of the yield curve. As I write, the yield on the 10-year Treasury note is below 2.5%, as the yield curve is flattening.

(Click here for the latest bond prices.)

The message of the bond market is not suggesting in any way, shape, or form, that the Federal Reserve is "behind the curve" on battling phantom inflation. Indeed, even despite the "flight to quality" trade in Treasurys, which is pushing yields lower than they might otherwise be, is hardly the sole reason for declining interest rates. A flattening yield curve and tightening credit spreads are hardly screaming out that inflation is just around the corner.

With respect to raging wage inflation, that argument is also a non-starter. Wages are rising at a 2 percent to 2.5 percent annual rate, hardly the stuff of wage-price spirals. Indeed, a rise in wages is not always inflationary, if accompanied by higher productivity, although the latter half of that equation has gone wanting.

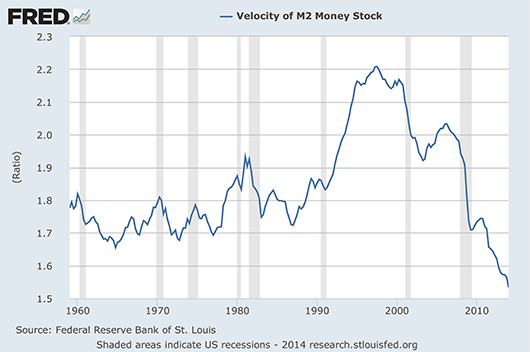

In pure monetary terms, the ingredients for runaway inflation are also absent without leave. This chart from the St. Louis Fed shows how the velocity of money (the speed with which the money supply turns over) is near zero. Velocity needs to accelerate markedly if one wishes to make the case that policy-inspired inflation is on the horizon.