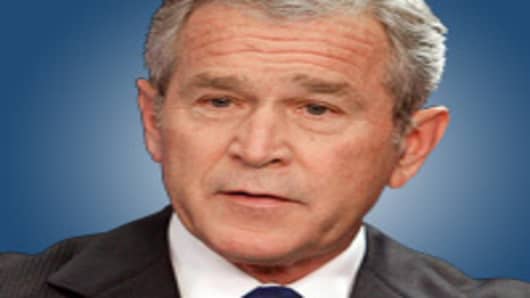

Presidential power ebbs and flows and George W. Bush is holding very weak cards just now. But as he likes to point out, sometimes with more than flattering zeal, he is still the president and everyone also just kibitzes.

And he is using the powers he has to make a difference in his waning months at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. His press conference earlier today, in which he vowed to sprint to his term's Jan 20, 2009 finish line, underscored both of his principal tools.

The first and less important is the bully pulpit. As president, Bush can still demand more news cameras and live television cameras than anybody else, no matter how big Hillary Clinton's lead in the polls becomes. That counts for something. He used it today to slap the similarly unpopular Congress around for dawdling while important business: from spending bills to anti-terrorist surveillance legislation to a response for the mortgage mess remains undone. Better, from his point of view, to do that than to let them slap him around unchallenged over his veto of the S-chip children's health care bill.

The reason I call the bully pulpit as less important is that Bush's credibility and persuasive power have largely drained away. He can rally the partisans, but few beyond that and even the ranks of Bush-loving partisans have diminished.

One case in point: the president today tried to justify his confrontational rhetoric toward Democrats in Congress by saying he had confronted Republicans over spending when they controlled Congress--and they listened. To all those economic conservatives who became embittered by the Bush-GOP spending record of 2001-2006, the president's statement will sound preposterous.