The annual meeting of China's handpicked Parliament, the National People’s Congress, is normally drama-free, the fate of its legislation and most other issues having been determined well in advance by the government’s higher-ups. This year could be an exception.

The reason has little to do with laws, but with the leadership transition taking place late this year at the top of the Communist Party and government. A handful of provincial officials who will be roaming the Great Hall of the People for the National People’s Congress, which opened Monday, are unannounced contenders for soon-to-be-vacant seats on the Politburo Standing Committee, the nine-member body that essentially runs the country.

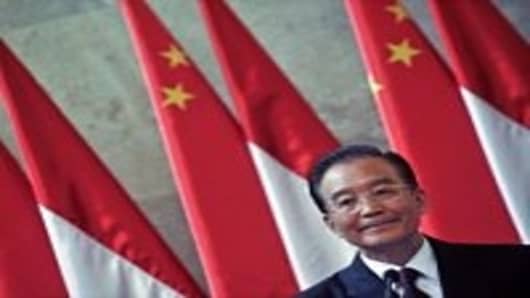

Vice President Xi Jinping and Vice Prime Minister Li Keqiang, the near-certain replacements for President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, are expected to keep their seats on the committee. But the other seven committee members are likely to retire, and top contenders who will be at the Parliament session include party chiefs from Guangdong Province, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing and Inner Mongolia.

Neither they nor any of the nearly 3,000 delegates is likely to say anything publicly about jockeying over the transition.

“People are not allowed to speak,” Zheng Yongnian, an expert on Chinese politics who directs the East Asian Institute at the National University of Singapore, said in an interview. Before the Communist Party congress this autumn, where leadership changes will be formally ratified, “stability must be the highest priority. They want to guarantee the coming transition.”

But behind the facade, he added, “you can feel a sense of nervousness over the changes at the top.”

Consider Bo Xilai, the atypically flamboyant party secretary of Chongqing, a provincelike metropolis in central China, who has been called a leading contender for the Politburo Standing Committee. Since his top deputy, Wang Lijun, spent a day last month at the United States Consulate in Chengdu — by many accounts, to seek asylum — Mr. Bo has seen his hopes for higher office waver. And China’s political gossip mills have bubbled with speculation that his troubles signal a power struggle within the Communist Party’s top ranks.

A government spokesman confirmed Friday that Mr. Wang was under investigation. He added that Mr. Wang, although a delegate to the National People’s Congress, had “taken leave” and would not be attending the session.

Mr. Bo was the grandstanding centerpiece of the National People’s Congress last year. This year for the first time, according to a report in the Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao, the Chongqing delegation to the National People’s Congress is being housed in a special hotel within the Great Hall of the People, under constant guard. An official at the hotel said Friday that it was “not convenient” to comment on the report.

The National People’s Congress runs nearly in tandem with a meeting of a party-appointed advisory body, the Chinese Peoples' Political Consultative Conference, which opened Saturday. While meetings of the groups’ committees and provincial delegations can be freewheeling, their formal agendas are largely free of controversy, including measures like one requiring product makers to eliminate waste in their packaging.

One highlight of the National People’s Congress will be the release of Mr. Wen’s annual report on China’s progress in meeting goals laid out in the nation’s five-year plan. The more notable measures expected to come up include a first-ever law covering domestic violence and a revision of the criminal code that civil-liberties advocates contend would drastically weaken the rights of people who are detained or under investigation.

The meeting also will be shadowed by two linked concerns: citizens’ growing demands for a larger voice in issues related to their lives, and the prospect of a slowing economy that could incite more social unrest. The World Bank and China's State Council released a joint report last Monday calling for an overhaul of the nation’s financial and economic systems and broad investments in the environment, education and other fields, warning that failure to act could diminish economic growth.

The two meetings also bring with them an annual security lockdown on Beijing, with vast cordons of police and other security officers deployed to prevent demonstrations or attacks. Officials already have barred chemical carriers and vehicles lacking Beijing license plates from entering the city, and they have set up police checkpoints on highways.

That is but the visible aspect of security work. Radio Free Asia cited an unverified document posted on the advocacy Web site canyu.org, in which officials in Anhui Province were ordered to start 24-hour surveillance of the Internet, step up surveillance of local citizens and watch for “hostile foreign forces” that might seek to stir up trouble.

The decree also ordered increased scrutiny of petitioners — citizens who take their unsatisfied grievances to Beijing each year in the usually futile hope that national leaders will solve problems that local officials have ignored.

Thousands of petitioners descend on the capital during the two annual meetings, with many of them detained by the police and sent back home on trains.

Li Bibo and Edy Yin contributed research.