Now that the U.S. has edged past Russia as the world's largest oil and gas producer, the drumbeat to export some of that oil bounty is expected to get louder as U.S. production continues to grow.

The North American energy picture has been evolving rapidly, as U.S. producers use drilling advances to extract oil and gas from shale rock and other difficult-to-access areas. That has created a boom, with the U.S. expected to produce an average 7.5 million barrels a day of oil in 2013 and 8.4 million barrels a day in 2014, according to the Energy Information Administration. The U.S. still imports about 8 million barrels a day.

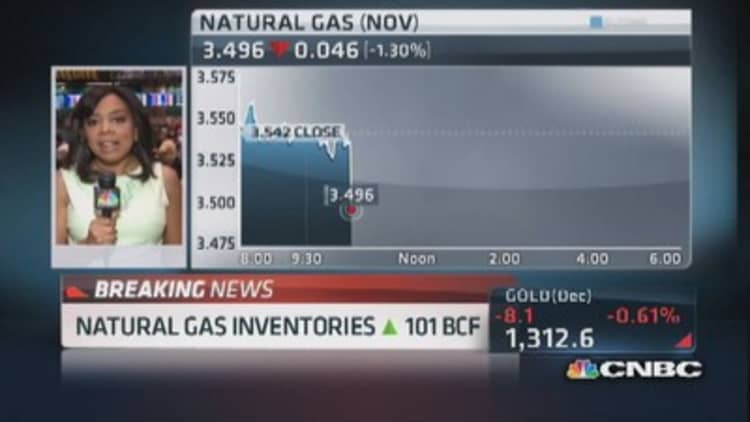

The U.S. also has the world's cheapest and most abundant natural gas supply. Increased exports of natural gas are already on the horizon, with four export terminals approved and expected to begin operating by 2015. But federal law prohibits the export of U.S. crude to most countries—only nations that have free trade pacts with the United States can be sent oil exports—even though the U.S. has become a net exporter of refined petroleum products and is looking to export even more.

"Obviously, we already had the debate about exporting natural gas, and the export of oil is, except in very minor exceptions, basically prohibited by laws that were passed in 1975 and 1979. But the economic logic of exporting some qualities of oil from some locations and importing oil to meet the needs of refineries is compelling, but it will be a hot debate," said Daniel Yergin, vice chairman of IHS. "It runs against 40 years of policy. Everybody forgets the U.S. was the largest exporter of oil once upon a time."

Unthinkable just a few years ago, North America is now well on its way to energy independence, with the percent of U.S. imports from overseas expected to continue to drop. Already, the U.S. had cut back imports from Africa.

"We are about 6 million barrels a day shy of it (energy independence) in the U.S. and we're 3.5 million barrels a day (short of it) in North America," said Edward Morse, global head of commodities research at Citigroup. "The question is not whether North America will be a net exporter to the rest of the world. The question is whether the president will choose to lift the restriction on the export of U.S. crude oil."

(Read more: Want to run your car on ... wood chips?)

Morse said the U.S. and Canada are several years away from producing surplus oil, and Canada is expected to increase the amount it is exporting, in part through the U.S. Gulf Coast. Canadian crude is expected to move south by train and by other pipelines, while the Keystone XL Pipeline is still held up, awaiting approval from the State Department.

"We have the timing of when pipelines should be opening and when Canadian flows hit the Gulf Coast. They should be hitting it pretty soon," said Morse. That impact should bump the cost of Canadian crude, which is now selling at a $30 to $40 below West Texas Intermediate. Morse said a surplus would help the argument that U.S. oil is abundant and not needed for strategic purposes. It would also change the world oil dynamic.

"We have longer-term implications for price. By the time we get toward the 2018 time horizon, the current $90 floor for oil prices will become a ceiling, and the trading range will likely drop to $70/$75 at the bottom," Morse said. "Our judgment is when you take the volatility out of the system, we're on a downward price trajectory. In 2018, there may be a day when North America is a net exporter of oil. We look as though by 2018 the U.S. could be as large as Qatar, the largest or second largest exporter of natural gas."

(Related video: US has long way to go: Hofmeister on oil independence)

Why is it illegal to export to most places?

Ken Hersh, CEO of NGP Energy Capital Management, said the U.S. is already exporting refined products like gasoline and diesel fuel, some natural gas, and is sending another valuable resource, coal to China. "The prohibitions on (oil) exports is really a holdover of thinking that the world's resources are scarce, and if we're importing it makes no sense for the U.S. to export, so we should not allow exports to happen because it would deprive us of some strategic assets," he said.

But Hersh, like Yergin, said it makes sense to sell some of the light sweet crude produced in places like the Bakken in North Dakota and buy the heavy crude of other producers, like Saudi Arabia, that can be processed in U.S. refineries.

"The way I look at it is the U.S. is a wonderful consumer of certain crude oil products. Some are light oil, some are heavy oil, and those come from different parts of the world," he said. "If we are in a world where we are not short, then the best thing for capital formation and productivity is to have the right product find the right consumer anywhere in the world. We have no problem exporting corn and soy beans even though we eat food."

Hersh said the economics of the global energy market will probably drive the U.S. to export, but it will be a ways off.

"The mindset is changing, we'll change and the policies will be a lagging indicator when they change," he said. "The energy markets are more powerful than any politicians."

(Watch: How US can change entire energy equation)

Oppenheimer senior analyst Fadel Gheit said it's not likely the U.S. will export crude, especially since it still imports so much. "It's like having your population hungry, and you're exporting food. We're still net importers," he said. He said it would make sense for the U.S. to trade some of the light sweet crude it produces for heavier oils, since the refineries were retrofitted to refine heavier oil.

Morse said he would not be surprised to see an application at some point to export crude to Korea, a free trade partner. The expansion of the Panama Canal, which allows ships to move between the Atlantic and Pacific, plus a glut of oil, could both hit the Gulf Coast at about the same time in 2015. He believes that is when the debate about whether the U.S. should export some of its own supply will pick up.

"That will have the same defanging impact of taking politics out of this business," he said.

"Russia is the prime example of a country that has tried to gain advantages from the use of oil as an instrument of politics and natural gas even more so," said Morse. "The OPEC countries, as a whole, are oriented towards trying when they can to withhold oil from the market to influence prices."

According to The Wall Street Journal, the U.S. is overtaking Russia as the world's largest producer of oil and gas. The U.S. EIA reports that the U.S. produced the equivalent of about 22 million barrels a day of oil, natural gas and related fuels in July, and Russia forecast its output at 21.8 million barrels a day, according to the Journal.

(Related video: Pumping natural gas)

But Morse said that, according to his calculations, the U.S. has already surpassed Russia.

"We'll continue to make strides on that. Our production base is rising very quickly, and theirs is stalled out," he said. "What the current trends have unleashed is the final victory of market forces over countries who dominate the export industry, who have used oil and natural gas as a political instrument."

Citigroup data show the U.S. surpassed Russian natural gas production in 2009, and in 2012, the U.S. produced 65.7 billion cubic feet a day, versus Russia's 57.1. That's 11 million barrels of oil equivalent, versus 9.82. Add to that U.S. production of oil and natural gas liquids of 11 million barrels a day at the end of 2012, and the U.S. surpasses Russia, which produced 10.6 million barrels a day.

"Yes we are the largest oil producer in the world, but we are the largest oil consumers in the world," said Gheit. "If we produce 9 million barrels a day of crude oil in addition to natural gas, we are consuming more than double that. Russia is a net exporter of crude but we are a net importer of crude, to the tune of 7 million barrels a day. It's a fact, and one important thing is that our production costs are the highest in the world."

—By CNBC's Patti Domm. Follow here on Twitter @pattidomm.