Elizabeth Holmes, the young CEO of blood-testing start-up Theranos, has had a standing invitation for the past few years to present at the annual summit for laboratory medicine, the conference of the American Association for Clinical Chemistry.

It was only after serious questions about her technology — and a ban on her operating clinical labs — arose this year that she finally accepted.

"We want to know what it is that she's so secretive about, how she's doing what she says she's doing," said Patricia Jones, president of the AACC and professor of pathology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. "We've been asking that since she first started advertising that she's doing this."

In theory, Theranos' promise was simple but revolutionary: make testing possible on just a drop of blood where competitors require tubes of it to do so. But in practice, it's become increasingly unclear if Theranos has been able to accomplish it.

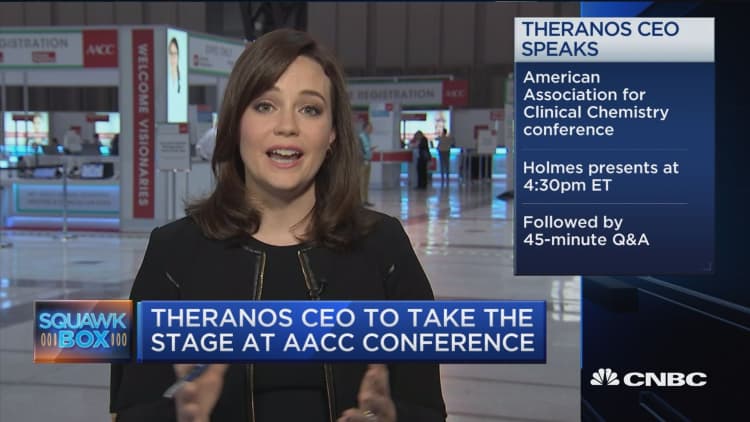

Monday, Holmes will make her case to the biggest summit of experts in her field. She's scheduled to make a 45-minute presentation on Theranos' technology at the 68th annual AACC conference in Philadelphia on Monday afternoon. Then she'll take questions for 45 minutes.

It's a crucial moment for the company. In less than a year, it has gone from being a Silicon Valley darling valued at $9 billion to what some suggest is a cautionary tale about the dangers of excess hype and providing insufficient proof to back it up.

Nothing speaks larger than data. They need to release data to the public.Dr. Joel DudleyDirector of biomedical informatics, Mount Sinai School of Medicine

The presentation at AACC marks the first time the intensely secretive Theranos will have presented information about its technology at a scientific conference.

"Nothing speaks larger than data," said Dr. Joel Dudley, assistant professor of genetics and genomic sciences and director of biomedical informatics at Mount Sinai School of Medicine. "They need to release data to the public."

Dudley published a study in March comparing Theranos' test results with those of established competitors Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp, finding that the Theranos results for cholesterol tests diverged significantly.

Published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, the outside study marked the first scientifically rigorous review of the technology.

"This one baffles me to this day," Dudley said in an interview Friday. "I still can't figure out why a bunch of geneticists and bioinformatics people from New York had to be the first ones to publish this study."

Dudley's group conducted the research in July 2015, three months before an October Wall Street Journal investigation raised doubts about Theranos' technology, a machine called Edison. From there, the story rapidly unraveled.

As Theranos disputed the Journal's reporting, federal regulators called the company's laboratory practices into question. In January, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services identified serious deficiencies at Theranos' lab in Newark, California. Theranos said it was taking "corrective action" and had already addressed many of CMS' concerns. It also operates a lab in Arizona, where it says it does the majority of its tests.

In March, CMS said Theranos had failed to sufficiently fix the problems in California, and threatened sanctions including a two-year ban from operating clinical labs for Holmes. Two months later, Theranos voided two years of test results in an effort to avoid the sanctions, according to the Journal.

In June, Walgreens ended its partnership with Theranos, shuttering 40 testing sites. The drugstore giant cited CMS' concerns over deficiencies as well as the test results voided by Theranos.

The major blow came in July: CMS said it was imposing sanctions, including the two-year ban for Holmes.

"Theranos is working closely with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to resolve the sanctions that the agency advised it plans to impose on the company's Newark, California, laboratory," the company said in a statement at the time, noting it has 60 days to appeal and was considering all its options.

Theranos has added two new executives to oversee regulatory, quality and compliance efforts, and recruited new scientific and medical advisory board members, including former CDC director Dr. William Foege.

In an op-ed published in The Hill last month, Foege said that he and others had a chance to review Theranos' technology and that he believes in its promise.

"Based on my experience, I believe that Theranos can collect, transport and test small samples, including finger-stick, with clinical integrity," Foege wrote. "This ability has break-through potential by expanding access to testing close to home or in remote locations."

Foege noted the potential in particular for Theranos technology to be used to test for mosquito-borne diseases like the Zika virus, "for pregnant women who are at risk for transmitting disease to their unborn or newborn baby."

"Theranos' tests are pending before FDA and, if authorized, would provide rapid access to critical information," Foege wrote.

But the technology is so mysterious, "to me it's almost like magic," AACC's Jones said. "That's why I want to see the science behind it."

That brings us to Monday, where Holmes' presentation is expected to cover a Theranos test for Zika, among others, according to a synopsis of the presentation on AACC's website.

Given the controversy around the company and the technology, there has been pushback among some AACC members to letting Holmes present at all.

"I still have some members that are not happy about the fact that we're providing her an opportunity," Jones said in a Friday interview. "I've tried to explain very carefully: We are not endorsing Elizabeth Holmes, Theranos and their technology."

"Nobody knows anything about them," Jones continued. "How could we possibly endorse them?"

Despite the spectacle, and the skepticism, there is hope in the field that Theranos might actually have something.

"This is a technology we hope exists," Mount Sinai's Dudley said, noting the reason he did his study in the first place is because he wanted to take advantage of it in his research. "We want to believe this technology can be possible."