As attempts to reopen the U.S. economy amidst the coronavirus pandemic struggle, a spotlight is on the Trump administration's enforcement of workplace safety laws, and a battle with unions, which claim the Department of Labor is doing too little to protect workers from a coronavirus that is increasing across many parts of the country.

More than three years after taking office, the administration has never filled the job running the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which is charged with enforcing workplace safety laws. The $560 million-a-year agency, whose estimated 2,000 inspectors performed 32,020 on-site inspections in 2018, spent months not doing any in-person inspections related to coronavirus, other than in hospitals, said Rebecca Reindel, director of occupational safety and health for the AFL-CIO.

OSHA has issued only one citation for violations of workplace safety laws related to Covid-19, according to its own testimony to Congress, to a Georgia nursing home that failed to report that a staffer had been hospitalized. The lone citation is despite well-documented shortages of required personal protective equipment at hospitals and Covid-19 outbreaks at meatpacking plants.

The dispute has spilled into the courts, as the full U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Columbia is being asked by the AFL-CIO to consider an appeal of a June decision by a court panel siding with OSHA and denying the labor federation's request for a rule that gives employers specific guidelines for dealing with Covid-19.

"We know 125,000 people have died, and we know the workplace is a major source of exposure," said Reindel. "Besides, it's the only place most people are going.''

A petition for a rehearing by the full court is pending, according to AFL-CIO general counsel Craig Becker. "We are hopeful that a majority of the judges on the court will give this critically important issue the attention it deserves. We expect a decision on whether the full court will consider the case soon," Becker said in an email to CNBC.

Worker illness and death

The dispute escalates as workplace exposures in meat packing plants move back into the spotlight, and as states like Texas and Florida pause efforts to reopen their economies. A surge in cases in Arkansas coincided with an outbreak at facilities run by Tyson Foods, where nearly 500 employees have tested positive for coronavirus, prompting China to halt chicken imports from the Springdale, Arkansas plant.

"The pandemic has already caused more illness and death among workers in a shorter period of time than any other workplace health crisis since the (Occupational Safety and Health) Act's adoption in 1970," lawyers for the AFL-CIO wrote in a June 18 petition to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Washington. "The risk to workers' lives is heightened now that the economy is reopening and millions of workers are returning to workplaces where many of them are certain to be exposed to the undisputed 'grave danger' posed by the coronavirus due to inadequate safety and health practices."

Tyson has been testing workers at facilities around the country, including in Arkansas, for which is released test results on June 19. Tyson also has put in place protective steps in collaboration with local health and government officials which it says meet or exceed CDC and OSHA guidance for preventing Covid-19 at its facilities, including symptom screenings for all team members before every shift, providing mandatory protective face masks, and social distancing measures, including physical barriers between workstations and in break rooms. It also has made the case that workers testing positive does not imply the workplace was the source of the problem — Covid-19 exposure is a community issue.

The broader debate is over whether existing safety laws are enough to protect workers in meat packing plants and hospitals. The government already has jurisdiction over employers' obligations to provide personal protective equipment, and a so-called "general duty rule" that requires businesses to provide a safe workplace. The union wants a specific standard, known as an Emergency Temporary Standard, for measures to stop coronavirus.

The government's response has been delinquent, delayed, disorganized, chaotic and totally inadequate.Richard Trumkapresident of the AFL-CIO

Brad Livingston, a partner at the law firm Seyfarth Shaw who chaired the firm's labor relations practice for over a decade, noted that unionized employers have a requirement under the National Labor Relations Act to bargain with unions over conditions including safety, and unions including the United Food & Commercial Workers International Union, Service Employees International Union, and the Teamsters, are among those at forefront of making demands on employers to assure workers are safe.

The United Food & Commercial Workers recently proposed new initiatives to protect frontline workers, such as those in health care, meatpacking and food processing plants, and grocery stores. It has called for a public mask mandate in all 50 states, and creating a new national public registry to track all Covid-19 infections in frontline workers, and requiring companies with more than 1,000 employees to submit monthly reports on worker infections and deaths.

"Some of our nation's biggest companies like Amazon, Walmart, and Kroger are still keeping us in the dark and refusing to tell the American people how many of their workers have died or been exposed to Covid-19," UFCW International President Marc Perrone said during a national press briefing on June 25.

All employers, whether union or non-union employers, are looking at guidance from the CDC and WHO, and state governors' recommendations: "An alphabet soup of guidance," Livingston said.

He said most employers are trying to do what they can reasonably do, including staggering shift times, more spacing in work areas like production lines, and greater sanitation. But Livingston said this will continue to be a balancing act because the truth is, "if you wanted to be perfectly safe, you would simply shut down, and that is not an option for most businesses or the economy," he said. Employers do need to be as safe as possible in reopening, because for many firms, especially smaller ones like restaurants and retailers, being forced to shut down again due to a workplace outbreak would likely lead to bankruptcy.

Scalia v. Trumka

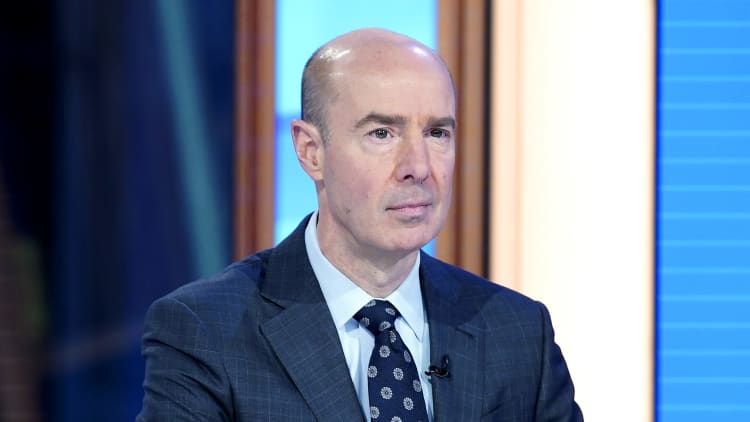

In a terse exchange of letters, U.S. Labor Secretary Eugene Scalia and Richard Trumka, president of the AFL-CIO, the nation's largest federation of labor unions representing about 12 million workers, have sparred over why inspections have been so rare and over whether the agency needs to implement temporary rules. Those would begin with requirements that employers provide masks and other protective equipment where needed, as well as ventilation standards, according to a Trumka letter to Scalia.

The tiff between Scalia and the unions began with a letter to Scalia from the union on April 28, arguing that the government "has failed to meet its obligation and duty to protect workers" and charging that "the government's response has been delinquent, delayed, disorganized, chaotic and totally inadequate."

Scalia countered that OSHA had issued voluntary guidelines to employers, which can be adjusted more quickly than fixed rules as more is learned about coronavirus. He added that employers were already working on the steps the union wanted mandated, such as upgrading personal protective equipment and upgrading workplace training to prevent disease.

"I appreciate that you may want different actions from OSHA, but to suggest ... OSHA is indifferent to worker protection and enforcement is to misinform employers about their duties and workers about their rights," Scalia said. "In fact, the cop is on the beat."

No top cop on OSHA beat

Management of OSHA has been a sore point for unions throughout President Donald Trump's tenure. His nominee to run the agency, an assistant secretary-level post, withdrew in May 2019 after the Senate failed to act on his confirmation for more than a year, leaving OSHA to be run by former congressional staffer and principal deputy assistant secretary Loren Sweatt.

"The Senate seemed more focused on pushing through judicial nominations," said John F. Martin, a Washington management-side labor lawyer who practices before OSHA. "Normally that spot gets filled by the summer of the president's inaugural year.''

A formal appointment would not necessarily be a win for worker protections. With the top role being a political appointment, it could go to an OSHA leader with an anti-union philosophy, making career bureaucrats in the agency less likely to perform their jobs without interference.

The AFL-CIO has pointed to a series of recent decisions in criticizing OSHA's leadership. The department suspended an interim requirement that employers of essential workers identify and record work-related Covid-19 infections. And an April 3 memo from OSHA tells employers that they can use face masks rather than respirators to protect workers without fear of citation.

The agency is investigating most worker complaints informally, sending letters or phone calls to employers rather than visiting workplaces, the AFL-CIO claims. However, an April 13 OSHA memo does allow for some in-person inspections at hospitals, which the union said happened only after widespread infections among health care workers. More than 21,000 health care workers have contracted the coronavirus, and at least 71 have died, according to Reindel.

Scalia, who was not available for an interview, has cited employers moving to add personal protective equipment and boost training of workers even in the absence of new corona-specific standards. He also argued that existing law gives OSHA authority to act where needed under employers' "general duty" to provide a safe work environment, as well as the standard that requires them to supply personal protective equipment.

The Labor Secretary argues that requiring employers to report all Covid-19 diagnoses among their workers to OSHA would "burden employers and overwhelm OSHA.''

"OSHA will not use guidelines as a substitute for enforcement,'' Scalia wrote to the union boss.

According to Mark Lies, a partner in Seyfarth Shaw's OSHA practice group, OSHA's lack of formal guidance does not come without reason. It is recommending employers follow CDC guidance and has made recommendations to employers for when to report infections to OSHA, though he added, "It's been spotty in terms of what they do, but have been putting out guidance," falling back on CDC or local health departments.

The agency received 3,667 coronavirus-related complaints since Feb. 1 and had closed 2,418 of them through May 12, according to Labor Department data shared with CNBC.

Lies said there have been many instances where unions have filed complaints with federal OSHA area offices and with state counterparts contending that the employer does not have a COVID-19 response program that complies with CDC guidance. They have also filed complaints with State Attorney Generals alleging that the employer is not complying with executive orders issued by governors which are based on CDC guidance.

Most complaint inspections are being done virtual, requesting extensive documentation from the employer. The complaints have ranged from failure to provide Covid-19 training, temperature screening, masks or face coverings, and hand sanitizer, to implement social distancing, failure to sanitize working surfaces including, the time clocks when employees punch in, tools, tables, cafeteria, break room furniture and toilet facilities. Some of the complaints have also resulted in OSHA conducting virtual interviews of hourly employees and managers.

"Their activity is up at OSHA, and in some cases, up to 50%of time is responding to employees calling up and saying they feel unsafe, or employees saying 'I was fired because I made a complaint that I didn't get a respirator.' Unions and employees both," Lies said.

Employee and union concerns are impacting resources at a time when OSHA's workload is too high for its current staff headcount, and it is also a particular kind of workplace crisis that the agency is not designed best to oversee.

"They are pulling people away from other legitimate hazard inspections that should be going on, accident investigations or program investigations [of broader sector violations]. ... OSHA is a political animal, so when they start feeling the heat about an issue, they start diverting resources," Lies said. "OSHA, frankly, is not equipped to be doing these inspections. It should be the departments of public health, but they are strapped too."

In fiscal 2018, the agency reported 5,250 work-related deaths nationwide, with the largest number coming from construction accidents.

The fight over a temporary OSHA rule

In June, OSHA rejected the AFl-CIO's demand for an Emergency Temporary Standard.

"OSHA has initiated thousands of investigations of complaints related to Covid-19, opened hundreds of inspections, and repeatedly emphasized the rights of workers,'' Sweatt wrote in a letter to Trumka. "Investigations and inspections are still open and could result in citations."

Investigations like these take as long as six months per establishment, whether the agency passes a special rule for Covid-19 or not, Sweatt wrote. Most often, they do not initially include on-site inspections, relying on reviews of employers' documents and policies. "Accordingly, OSHA's issuance of only one citation so far is not surprising," she said.

Initially, the union lost its bid to get court action ordering the agency to act, as a panel of the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Washington ruled the agency has broad discretion in how to do its job. The AFL-CIO has now asked the full circuit court for a rehearing.

"The agency is authorized to issue an ETS if it determines that employees are exposed to grave danger from a new hazard in the workplace, and an ETS is necessary to protect them from that danger," the panel wrote. "In light of the unprecedented nature of the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as the regulatory tools that the OSHA has at its disposal to ensure that employers are maintaining hazard-free work environments, the OSHA reasonably determined that an ETS is not necessary at this time."

Lies noted that the CDC has changed guidance based on an evolving public health crisis, and that is one reason why OSHA would not want to dive into a new regulation. Even an ETS can be difficult to devise, and as an agency with no research capabilities, no laboratories to study a virus or develop virus protocols, relying on CDC guidance and reverting to its general duty rule for enforcement authority, makes sense, the lawyer said. The general duty rule address workplace hazards and the power to cite employers, and has been in effect since 1971.

"The general duty rule was used by OSHA for swine flu, Zika and Ebola. ... They have the authority, even though they don't have a standard for Covid-19," Lies said.

—Additional reporting by CNBC's Eric Rosenbaum

For more on tech, transformation and the future of work, join the most influential voices disrupting the next decade of work at the next CNBC @Work Summit this October.