Over the last decade, Mr. Ackman and Mr. Loeb have developed a reputation for their aggressive tactics, capitalizing on their rock-star status in finance to gain support for their strategies. Unlike many of their hedge fund compatriots, the activist investors are unafraid to take big positions in companies and demand change in very public ways.

They overhaul management teams, remake boards and dictate strategy, all in the hope of increasing their holdings. Or they just bet against a stock, if they don't have faith.

Last year, Mr. Loeb was instrumental in the ouster of the Yahoo chief executive Scott Thompson. The activist investor, known for his acerbic pen, wrote scathing letters to the board of the Internet company, detailing how Mr. Thompson had padded his rsum.

"Now more than ever Yahoo investors need a trustworthy C.E.O," Mr. Loeb wrote at the time. Since the firm first took a stake in 2011, shares of Yahoo are up more than 50 percent.

Mr. Ackman turned a $60 million investment in General Growth Properties into a $2.3 billion windfall by navigating one of the nation's largest mall operators through bankruptcy. After taking a seat on the board, he successfully fended off a lowball takeover attempt while orchestrating a better deal.

They are not always successful. Mr. Ackman took on Target, battling with the retailer's board in 2009 over how to improve its stock price. After spending millions of dollars on his campaign, he conceded defeat.

He is also bullish on a turnaround at J. C. Penney, bringing in the former Apple retail chief Ron Johnson. But since his first investment in late 2010, Penney's stock has fallen 31 percent.

During the financial crisis, Mr. Loeb's firm suffered along with many of his peers. His main fund lost about 33 percent in 2008.

Only one investor will be right on Herbalife.

In late December, Mr. Ackman announced an "enormous" short position in the company, in a three-hour presentation called "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?" The investor cast doubt on the company's sales of nearly $4 billion a year.

"I don't think very many retail sales are actually happening at all," said Mr. Ackman, who pledged to donate his personal proceeds from the bet against Herbalife to charity.

With his usual showmanship, Mr. Ackman also highlighted what he considered the more dubious aspects of the company's culture. He showed an Herbalife video, featuring a tour of a distributor's high-end home.

"Episodes of 'MTV Cribs'?" Mr. Ackman asked. "No. These are Herbalife productions."

In the end, the short-seller had a bold prediction: federal regulators would eventually shut down the company.

The investor's statements sent the stock tumbling. Over the next four days, shares of Herbalife fell 30 percent. Months before, critical questions on a company's earnings call by the activist investor David Einhorn prompted a similar sell-off, although the stock had started to recover before Mr. Ackman's presentation.

Soon after Mr. Ackman's campaign began, Mr. Loeb met with the company executives and bankers about Herbalife's business, according to people with direct knowledge of the matter. He also conducted his own research, digging through the numbers.

The investor eventually decided Mr. Ackman was wrong, buying 8.2 percent of Herbalife. When Mr. Loeb disclosed the stake, he breathed life in the stock. It rose 4 percent on Wednesday to close at nearly $40, higher than when Mr. Ackman delivered his presentation.

Mr. Loeb indicated in a letter to investors that the shares had room to run, given the company's strong revenue, profit and free cash flow. Over all, he estimates Herbalife stock is worth as much as $68.

"While the short-seller's presentation was lengthy, it presented no evidence to show that Herbalife has crossed a line that would compel regulators to shut it down," Mr. Loeb wrote, taking a shot at Mr. Ackman. Mr. Ackman promptly responded, welcoming any investor who "brings additional sunlight to the situation."

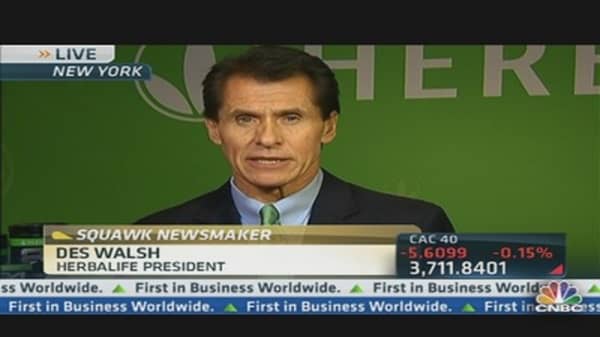

On Thursday, Herbalife will tell its side of the story. The company will present to investors its first public rebuttal since Mr. Ackman's attack last month.

Ben Protess and William Alden contributed reporting.