From the pulpit of his Miami church, pastor Kevin Sutherland appears more like a college lecturer than a firebrand preacher.

In video of a recent service posted on Mosaic Miami Church's YouTube channel, Sutherland strolls across the stage in shirtsleeves, using a PowerPoint presentation to talk about marriage and relationships.

"Effective communication enables relationships to endure," Sutherland tells the audience.

It is unclear from the videos or the church's web site how large the congregation is, but authorities allege Sutherland, 45, had a lucrative business on the side: dealing in counterfeit art.

(Read More: How to Spot a Fake: Paintings)

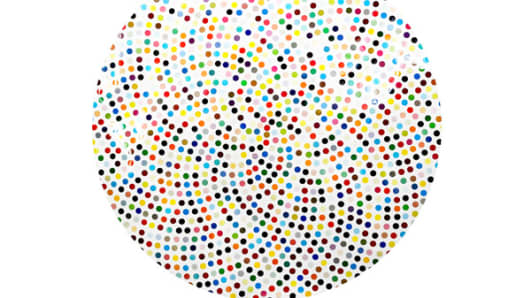

Last week in New York State Supreme Court in Manhattan, Sutherland pleaded not guilty to a single count of second degree attempted larceny. Prosecutors say he tried to pass off five paintings purportedly by British modern artist Damien Hirst, even though he knew they were fake. Sutherland was unaware that a supposed art dealer he met with at New York's Gramercy Park Hotel in January was, in fact, an undercover New York City detective.

Sutherland had allegedly contacted Sotheby's auction house in New York in December offering to sell a Hirst "spin" painting—reminiscent of spin art at carnivals—purported to be worth between $120,000 and $140,000. He also offered documentation—known as "provenance"—of the painting's history.