Twenty years and some 12,000 points later, the stock market is at a record high, volatility is relatively low and Wall Street is marking the crash of October 1987 with a dose of nostalgia and … perhaps some dread?

After all, just two months ago, with credit market problems in full bloom and the 2007 rally wilting, plenty of people were asking – “Was a market crash of the proportions of the October 1987 one possible?”

Pretty much regardless of whom you ask – economic historians, statistical theorists, Wall Street veterans, behavioral economists, politicians – the answer is: Yes, Black Monday can happen again.

That answer, however, is not as black and white as it may seem.

“I don’t see why not,” says William Silber of NYU’s Stern School of Business, taking a largely empirical view. “This is a low probability event. You need a lot of time for a low probability event to occur.”

Statistics bear that out. The most the market has fallen on any given day since the crash of ’87 is about 7 percent, and that includes the day the market opened following the Sept. 11 terror attacks.

Some market historians and academics now think that in retrospect the crash day itself was something of a non-event, a historical footnote or sorts, because it led to neither a recession nor a bear market. Indeed, people and firms lost lots of money but many of the same ones made much money thereafter.

“People laugh when I say this but it’s not a big deal,” quips Eugene Fama of the University of Chicago’s Graduate School of Business. “In the Great Depression, it was followed by further declines. This one didn’t last long.”

Then And Now

Much about the market has changed today from an explosion in trading volume and the number of investment products to the abundance and speed of information to the communication between exchanges and governments.

Take daily trading volume, for example. In 1987, volume rarely broke 200 million during the heady days of the record-breaking rally before the crash and it wasn’t that common after the crash. Daily trading volume topped the 600 million-level on only two days, Oct. 19-20 and surpassed 400,000 shares on one other day, Oct. 21. By contrast, trading volume passed the daily 5 billion-mark in June 2007

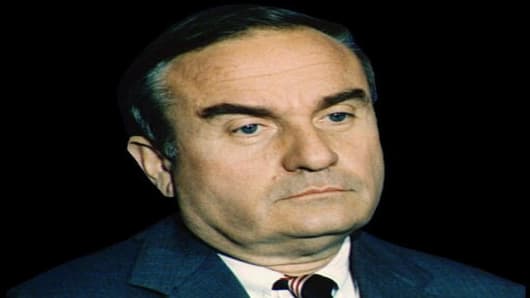

Robert Stovall, a managing director for Wood Asset Management who started at E.F. Hutton in 1953 and whose father worked on Wall Street during the 1929 crash, ticks off a list of differences in the markets and investing.

“We’re not as American-centric as we were then,“ says Stovall of the 1987 period. “There are more players, more markets, more liquidity, a lot more instruments, more diversification, more cushioning.”