New York Gov. Eliot Spitzer resigned amid a scandal over a $1,000-an-hour prostitute, ending a career built on pugnacious investigations of Wall Street crimes and an image of moral rectitude.

Lt. Gov. David Paterson will replace him next Monday, Spitzer announced in a brief statement that dwelt on his remorse for "private failings."

Spitzer, a Democrat, had faced intense pressure to resign and impeachment threats from Republicans after The New York Times reported on Monday that he was caught on a federal wiretap arranging a meeting with a prostitute in a Washington hotel room.

He still faces possible criminal charges. The chief federal prosecutor investigating the prostitution ring in question announced that has not reached an agreement with Spitzer about settling any criminal matter.

Spitzer, 48 and married with three daughters, is a former New York state chief prosecutor who rose to prominence by investigating financial crime with a publicity-conscious vigor that earned him the nickname Sheriff of Wall Street.

He also broke up prostitution rings as attorney general.

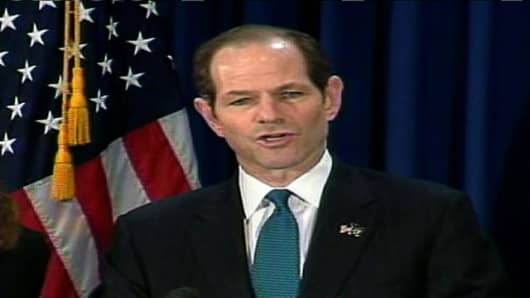

"Over the course of my public life I have insisted, I believe correctly, that people, regardless of their position or power, take responsibility for their conduct. I can and will ask no less of myself. For this reason I am resigning from the office of governor," Spitzer said.

Once viewed as a rising star among Democrats, Spitzer made his announcement in a grim-faced appearance at his New York headquarters, with wife at his side.

His disgrace was cheered by some financial power brokers who resented what they considered his heavy-handed and self-righteous ways.

"Wall Street is enjoying he got his comeuppance," said Michael Metz, chief investment strategist at Oppenheimer.

Spitzer made no specific reference to the allegations surrounding him. He had also given no details when he apologized to his family and the public on Monday for what he called a "private matter."

Between the two appearances he shuttered himself inside his New York City apartment as pressure grew for him to quit and reporters massed outside.

"He was an icon, a model of integrity, an enforcer of public and private morality and then you've got this utter hypocrisy," said Douglas Muzzio, professor of political science at Baruch College in New York.

"You can't help but be disillusioned."

Spitzer became governor with nearly 70 percent of the vote in November 2006 on pledges to clean up state politics. But 70 percent of New York voters wanted him to quit, according to a

WNBC/Marist poll conducted on Tuesday.

His resignation helped resolve the political paralysis that has gripped the state capital, Albany, over past two days.

Paterson will be the first New York's first black governor and the first legally blind governor in U.S. history.

Spitzer's legal situation was not yet clear.

Amid speculation that he was attempting to reach a plea deal to avoid or reduce any criminal liability, a federal prosecutor said no such pact had been reached.

"There is no agreement between this office and Gov. Eliot Spitzer, relating to his resignation or any other matter," Michael Garcia, U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, said in a statement.

Garcia's office is investigating the prostitution service that Spitzer reportedly used.

The Times, citing unnamed law enforcement officials, reported on Monday that Spitzer was the man identified as "Client 9" in a federal affidavit revealing details from the investigation.

Client 9 arranged to meet with "Kristen," a prostitute who charged $1,000 an hour, on Feb. 13 in a Washington hotel and paid her $4,300, the court document said.

The complaint unveiled last week charged four people with running a prostitution ring dubbed The Emperors Club.

Although prostitution is illegal in most U.S. states, legal experts said Spitzer was unlikely to face charges as a client but could be legally vulnerable over payment methods.

The Times reported that federal authorities were first alerted to the case by a bank that reported its suspicions about the way Spitzer was transferring money.