Most of Route 66 is long gone from U.S. maps.

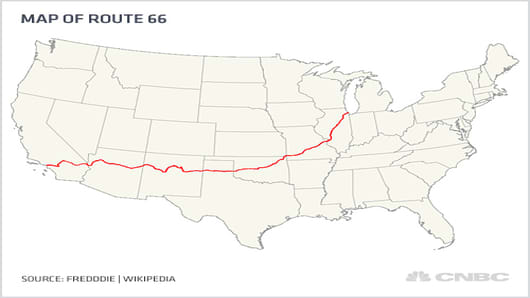

The series of roads that connected Chicago, Ill., to Santa Monica, Calif., is found mostly on Google searches, in specialty publications or by historic markers.

But the worldwide mystique Route 66 holds—along with a nostalgia for open road travel—has encouraged some entrepreneurs to revive the roadway's once thriving business communities.

"This has far exceeded our expectations," says Kevin Mueller, who along with his wife Nancy, own the Blue Swallow Motel in Tucumcari, N.M. "There's great history behind this place and we couldn't be happier running it."

The two 50 year olds left their native Michigan after losing their jobs—he in automotive service industry and she in real estate—and bought the decades-old Blue Swallow in 2011 for a low six-figure price with their retirement savings.