Some departments have back filled open jobs with civilians at a lower pay grade to work as dispatchers, computer specialists, budget administrators and clerks. In police circles, it's called "civilianization."

Others have turned to unpaid citizens, from neighborhood watches to volunteers who help solve cold cases. The Justice Department's Volunteers in Police Service (VIPS) Program matches citizens with police department needs – a kind of eHarmony for volunteers, according to Firman.

But relying on civilians only goes so far.

"A trained police officer—armed and constantly recertified—that's a big investment," said Firman. "But the public still has the expectation and desire that they're going to have a sworn, badge-wearing law enforcement officer come to their home."

Those citizens also want to see the name of their city or town on that officer's badge. That's a big reason there are some 18,000 separate police departments in the U.S., far more than in other developed countries. Despite budget pressures and widespread layoffs, the idea of turning to outsiders for police protection has been a tough sell in most communities.

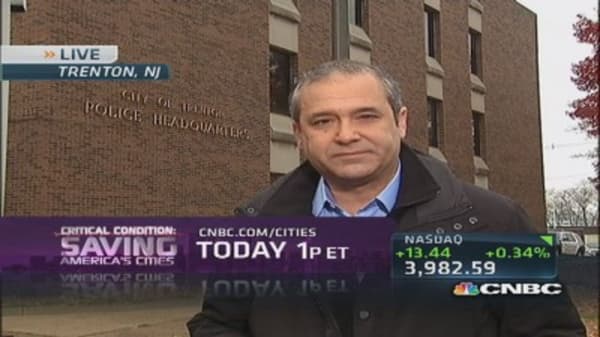

In Trenton, there a good chance the cop who responds to a given call will be wearing a New Jersey State Police badge, after state police were deployed to combat a surge in crime this summer. The extra patrols help, but they can't built the same level of trust with the people they're trying to protect, according to Darren Green, president of the Trenton Council of Civic Associations.

"Inside a lot of minority communities your hear 'stop snitching'", he said. "There's a culture where you see wrong and you don't report wrong but you're offended when wrong happens. I've been with officers who rolled up on a scene where shooting just occurred and there's forty people outside and nobody saw anything. So should that officer really care about you when you don't care about yourself? There has to be ownership on both sides."

In Trenton, and other cities coping with deep cutbacks in police payrolls, there are limits to "doing more with less." Calling on state police for reinforcements is just a "band-aid," said Turner.

"We need to get more boots on the streets," she said. "We've got to restore our police force to the level it was before the layoffs."

But for now, the money is just not there. Like some three dozen other states, New Jersey has imposed a cap on local property taxes, barring cities and towns from raising them more than two percent a year.

Trenton's mayor, Tony Mack, has asked the state for emergency funding. But his appeal has undermined by allegations of corruption after a federal grand jury indicted him in December 2012 on bribery charges. Several key members of his administration also have been charged with other, unrelated crimes.

So when Mack asked New Jersey governor Chris Christie for state funds in August to help hire 75 police officers, Christie said no way.

"I have no response to anything the indicted mayor of Trenton has to say," Christie told reporters at a news conference.

That standoff between the state of New Jersey and its capitol city is an extreme case. But the role of state government in restoring public safety to deeply depressed cities like Trenton is being debated in statehouses around the country.

One thing all sides agree on: wider efforts to rebuild broken cities can't succeed until public safety is restored. As long as businesses and citizens live in fear, many of the nation's hardest hit cities face a bleak future.

"Are we going to really try to reclaim these areas and make them viable?" said Jeffrey Keefe, a labor economist at Rutgers University. "Or are we going to just declare certain areas as unsafe, no-go places where an indigent population lives and gets victimized by criminal elements? That's certainly a way to drive business out and guarantee that were not going to revitalize them. Because nobody is going to want to operate in there."