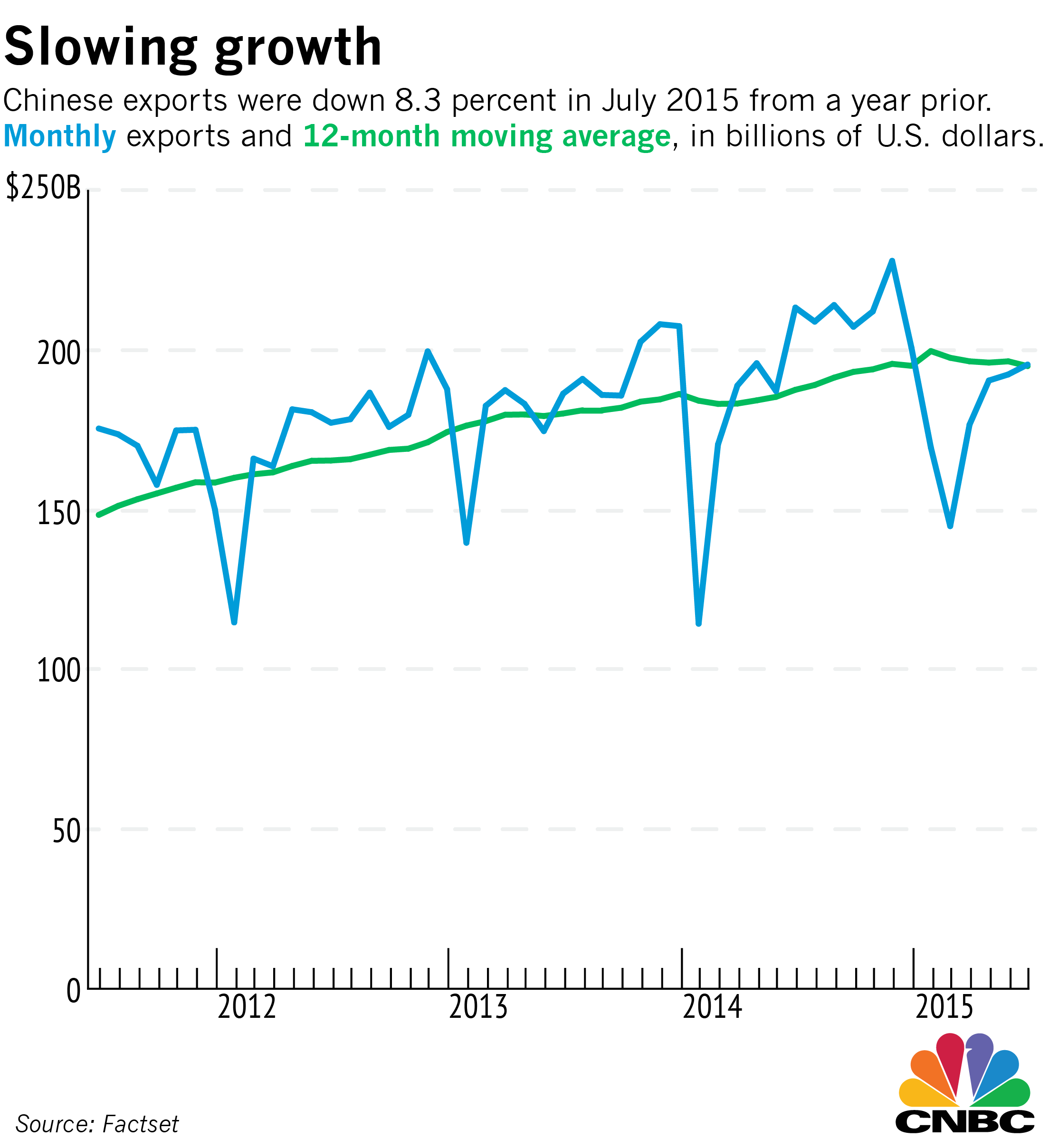

Stock markets around the world were shaken Wednesday on news that China had weakened its currency—for the second time in as many days—in a step to boost a slowing economy.

The People's Bank of China set the yuan's official rate at 6.3306 to the U.S. dollar, down 1.6 percent from the previous day and following a 1.9 percent devaluation on Monday. According to Reuters, government officials have been seeking a devaluation of as much as 10 percent to help the country's struggling exporters.

Read MoreThree charts that explain China's stock market

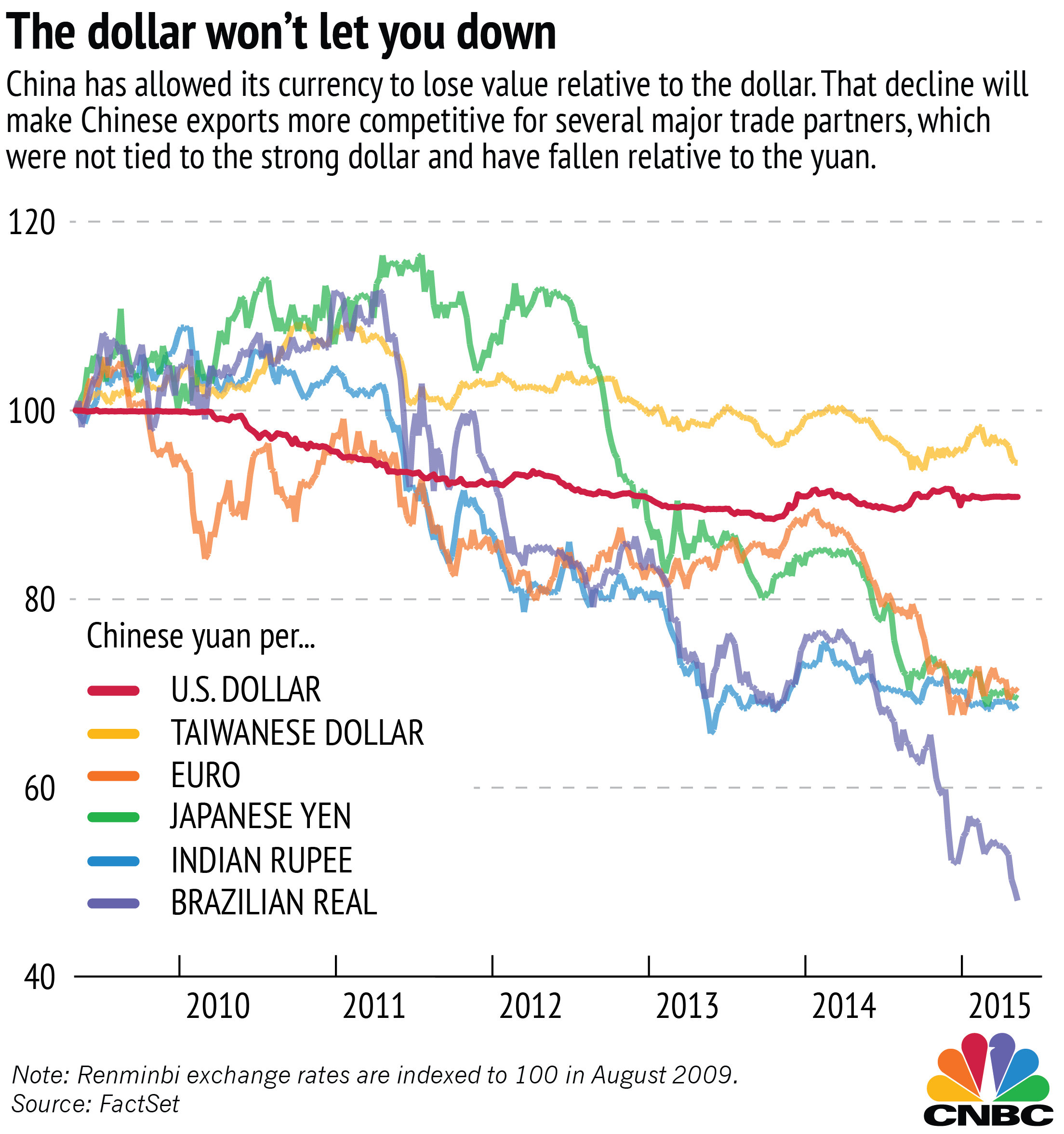

Now is a convenient time for the government to allow the currency to fall. By linking the yuan to the dollar, the government forced exporters to ride along with the strong dollar, which is up almost 20 percent from a year ago, relative to the basket of world currencies in the U.S Dollar Index.

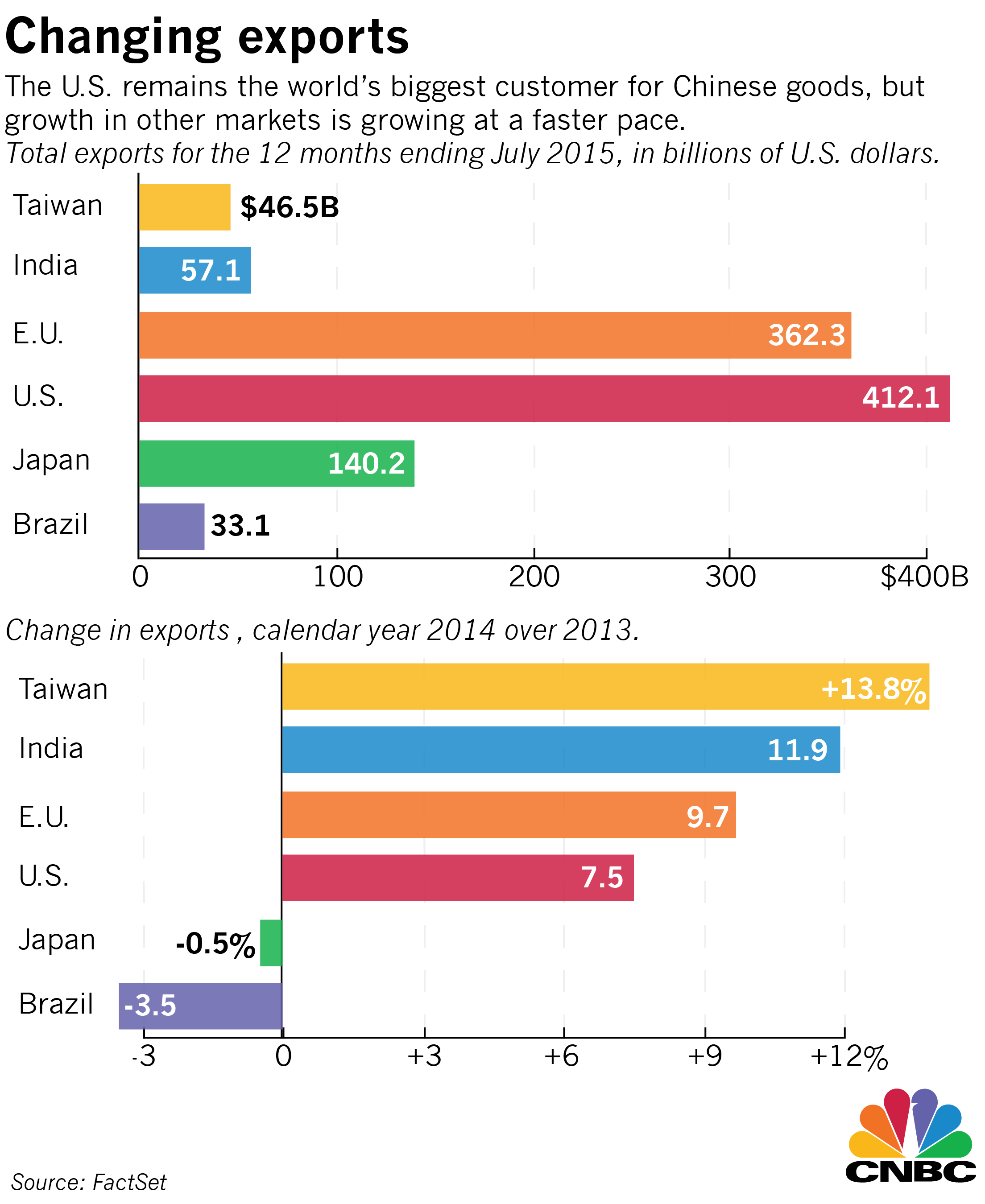

That means that as the U.S. dollar has risen, China has found itself becoming a less competitive exporter to some of its most important trade partners.