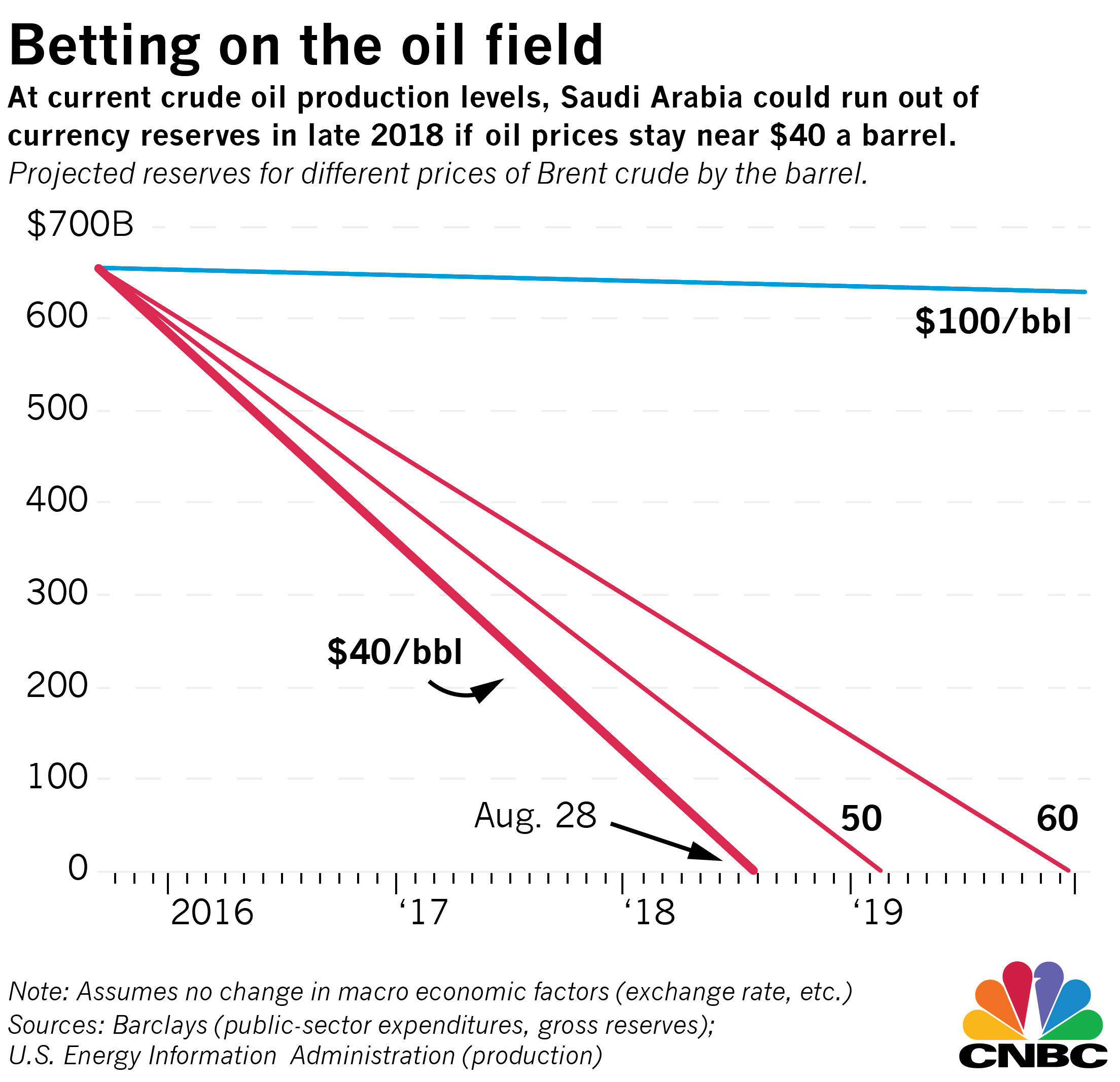

Mark the date on your calendars: Aug. 28, 2018.

That's when Saudi Arabia goes broke.

Or at least that's the date according to one model of the oil-rich nation's reserves, crude production and the price of oil. If crude stays around $40, America's Middle Eastern ally will run out of money on that date. Obviously, that assumes no other changes in fiscal or monetary policy. But regardless, it's an exercise that helps show exactly how important the price of oil is, and why Americans who value Middle East stability would want to see an increase in oil.

Without a recovery in the oil market, nations face huge budgetary shortfalls and increased political volatility over the coming years. Small, rich nations like Qatar and Kuwait likely have enough cash reserves to ride out the storm for a very long time, but poorer OPEC members like Libya, Iraq and Nigeria face potentially explosive situations.

Somewhere in the middle of that mix is Saudi Arabia, at once rich and at the mercy of the oil market. Crude accounts for about 90 percent of total export value and around 80 percent of total government revenue.

Saudi Arabia needs the price of oil to rise—and quickly, according to data put together by the "Big Crunch." "With the market still oversupplied and key producers pushing exports to record levels, that reset looks increasingly imperiled," researchers at RBC Capital Markets wrote in a recent note.