Volkswagen shares slid more than 34 percent this week following news that the German automaker would stop selling its "clean diesel" cars in the U.S. Last week, environmental regulators accused the company of installing software to evade emissions standards.

Monday was the biggest one-day drop for VW since February 2009, and losses amounted to about $15 billion in market value. That's some amazing movement, especially considering that it's about 482,000 cars in the U.S. that are involved in the alleged misdeeds.

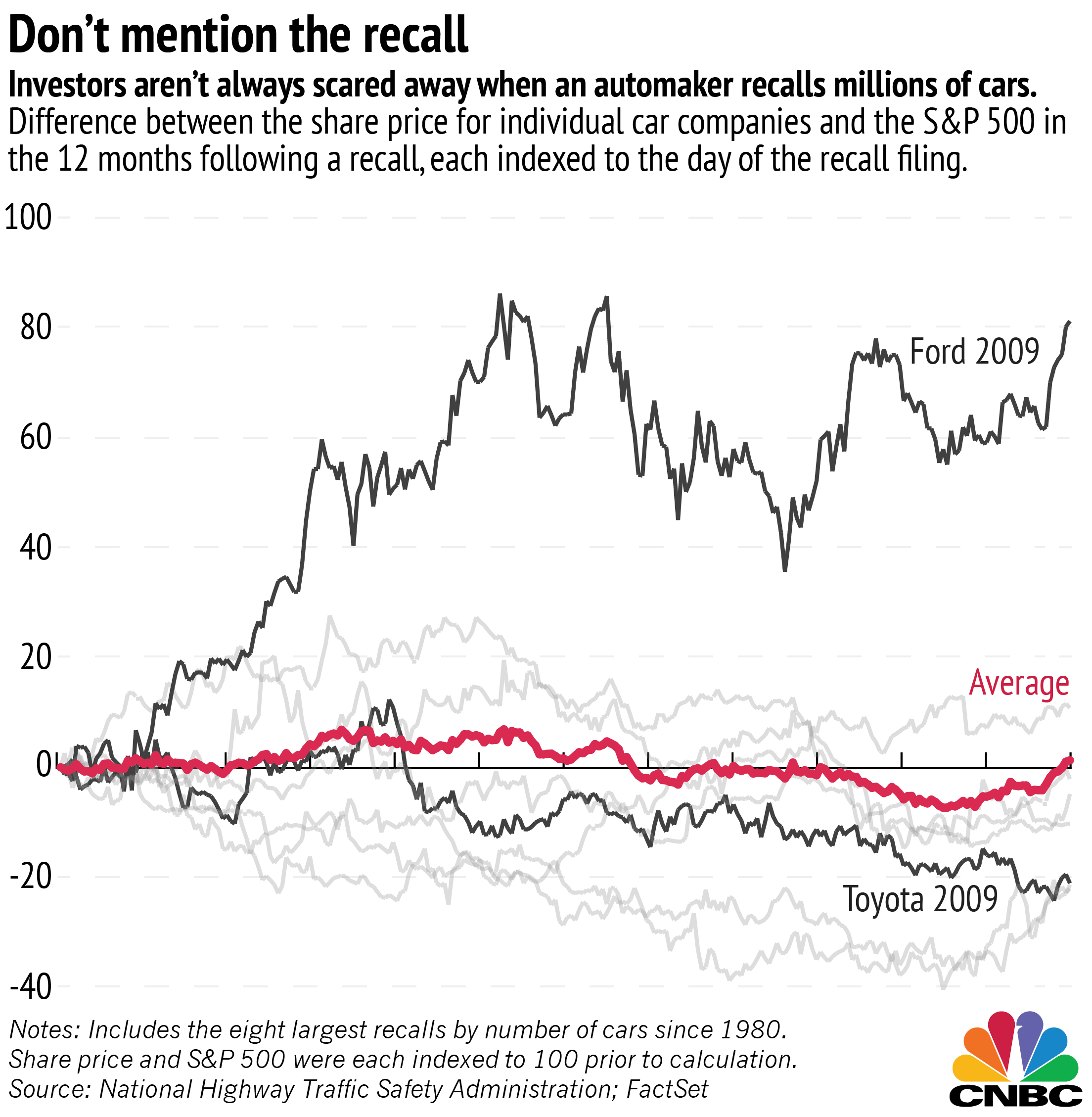

Data show that VW's drop is unusual for automakers involved in big recalls. A Big Crunch analysis suggests that investors in the past decades have not been significantly bothered by market fears associated with auto recalls.