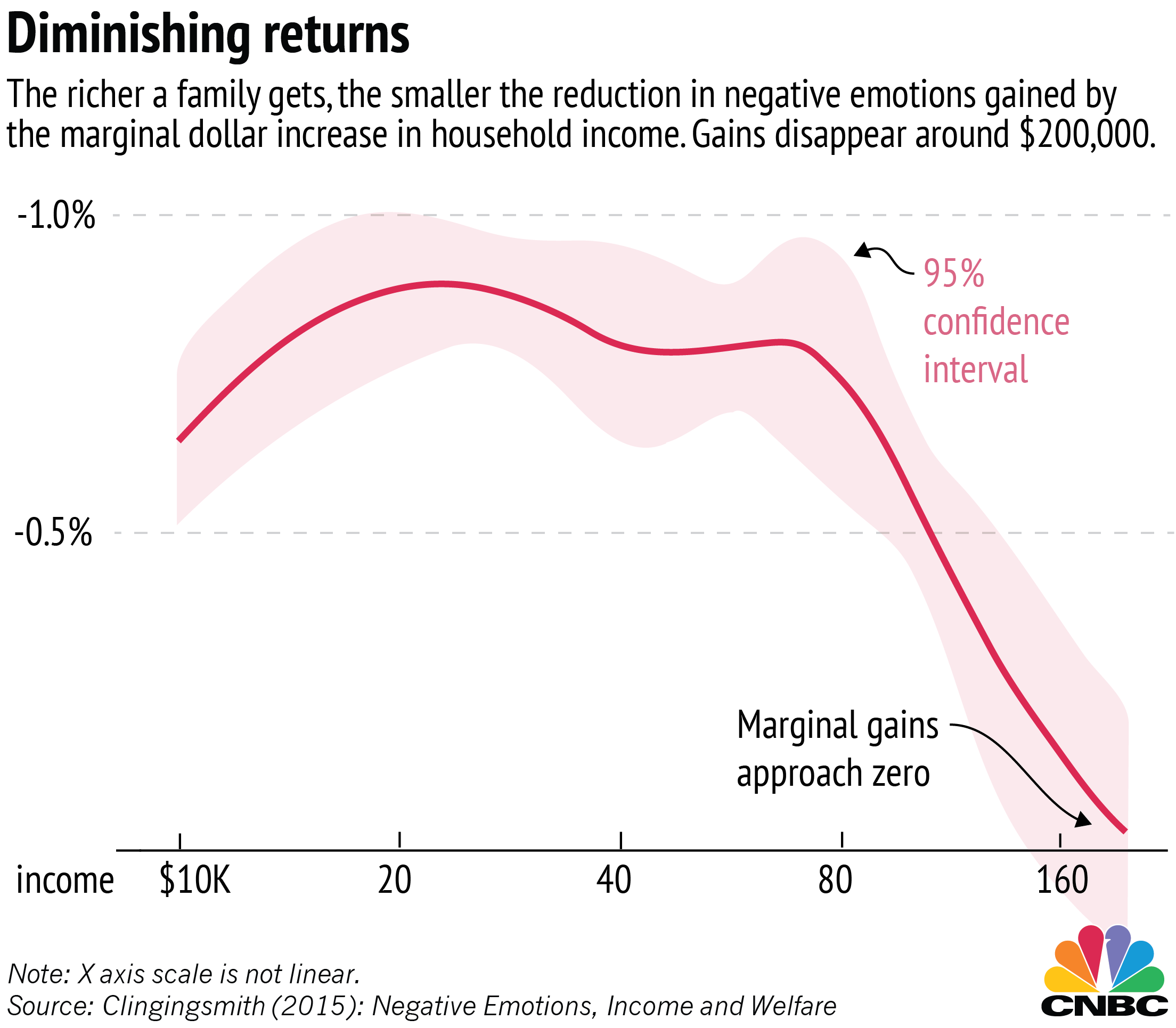

Those results are remarkably similar to the correlations reported in a 2010 study that found that people don't get happier after $75,000 a year.

That study analyzed data from the Gallup Organization in the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index (GHWBI). It's a lower number because researchers in that case used a single person's income rather than the family income used by Clingingsmith.

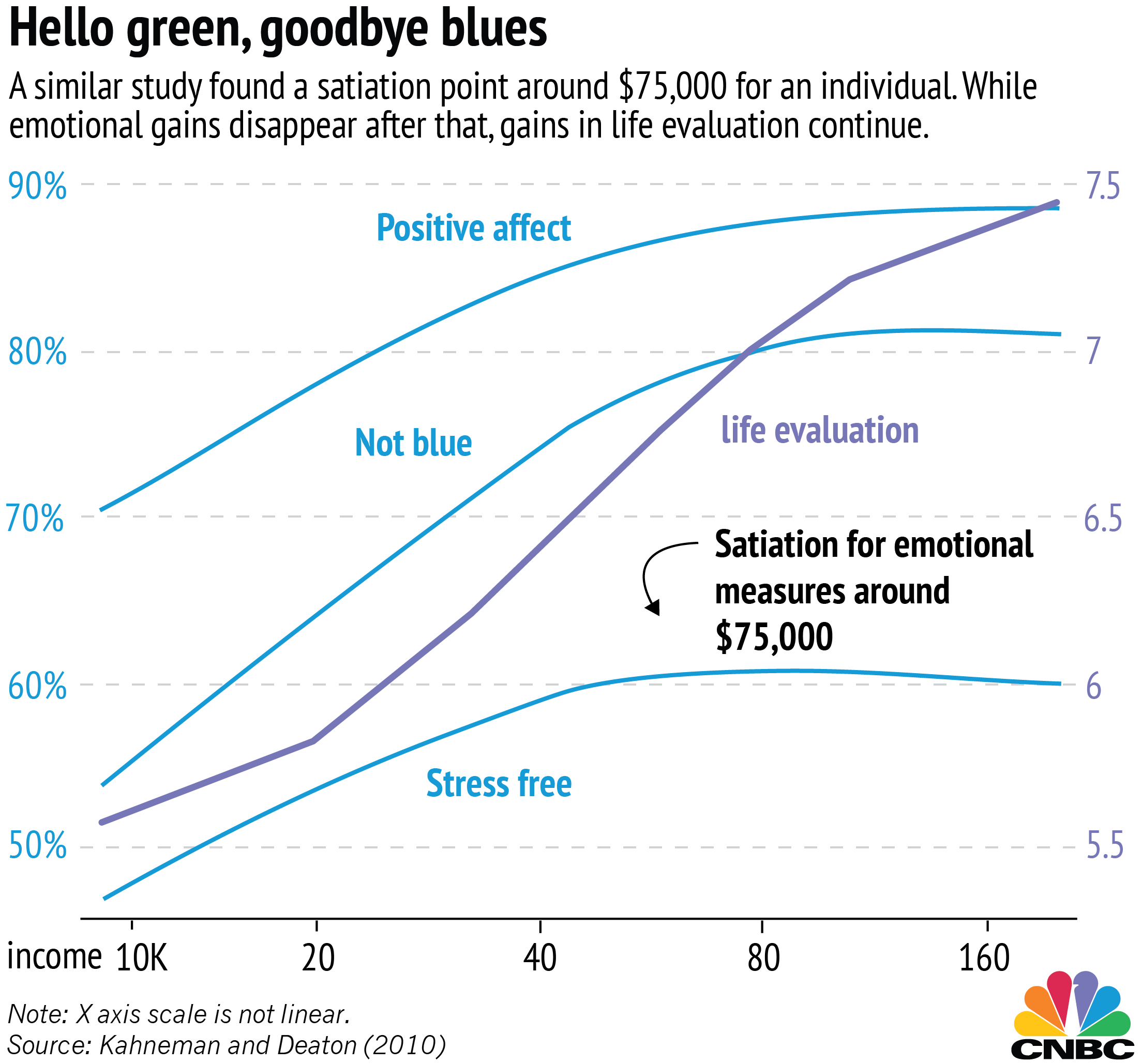

While the 2010 study found that three different measures of positive emotion (or lack of negative emotion) saw rapid improvement that slowed to nothing around $75,000, it also looked at a fourth metric that continued to rise far after that point.

That metric was "life evaluation" — a scale that asks the respondent to rate his or her life from 0, "the worst possible life for you," to 10, "the best possible life for you." It can be thought of as a measurement of how a person judges the success of their own life, rather than the feelings they experience while living it.

That measure seems to be more sensitive to socioeconomic status, the authors noted. People naturally compare their lives and incomes to others', and even if they experience no negative emotions they may yearn for and be more satisfied with higher pay far beyond the level they would need to avoid pain or afford leisure.

"That comparison between yourself and other people is really important for one's sense of well-being," said Clingingsmith. "If I'm a trader and making $300,000 at a firm where everyone else is making $450,000, that may feel different."