The hit to the U.K. economy from leaving the European Union (EU) that has been forecast by bodies ranging from the International Monetary Fund to the Bank of England is "rotten propaganda," a former U.K. finance minister and member of the Brexit camp told CNBC on Tuesday.

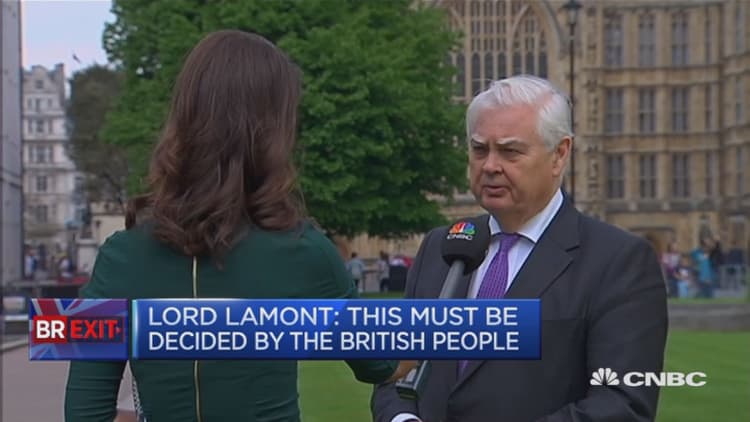

Norman Lamont is a veteran of the U.K.'s ruling center-right Conservative Party and among those leading the campaign to persuade Britons to vote to leave the EU in June 23's referendum. This week, he poured scorn on the flurry of well-respected economic bodies and economists that have warned in recent weeks about the dangers of a so-called Brexit.

Those raising concerns include U.K. Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, Bank of England Governor Mark Carney, the U.K.'s National Institute of Economic and Social Research, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the International Monetary Fund.

Lamont told CNBC that the various bodies were suffering from "groupthink."

"We've got a whole series — OECD, IMF, Bank of England, the (U.K.) Treasury — they are more or less the same people who talk to each other all the time. There is a lot of groupthink here. It doesn't mean they are right," he said on Tuesday.

The U.K. Treasury estimated in April that Britain would be worse off by £4,300 ($6,192) per household per year after 15 years outside the EU, a forecast Lamont called "rotten propaganda."

"Who can really tell whether the economy is going to grow faster or slower in 15 years' time?" he said.

Lamont served under Margaret Thatcher, one of the U.K.'s most influential prime ministers. Both were long-term skeptics of the EU and, as Chancellor, Lamont helped negotiate the U.K.'s opt-out from joining the euro. He threw his support behind the campaign to leave the EU in March this year.

Why the referendum?

The so-called Brexit referendum stems from the promise of current U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron to hold a public vote on leaving the EU if awarded a second-term as leader — which he was in 2015. The vote will take place on June 23 and is expected to be close run.

Membership of the EU, which the U.K. joined in 1973, guarantees freedom of movement of goods, services, people and capital among the 28 countries in the region that belong. Countries contribute to the EU budget in proportion to the size of their economies and must comply with certain union-wide regulations. Its proponents say the union has played a key role in maintaining peace and economic prosperity following the devastation of World War II.

As Europe's second-biggest economy, the U.K. is one of the biggest contributors to the EU budget, contributing around £8.5 billion in 2015. This is controversial among the British public, which has long been more skeptical of membership than the other major economies in the union, France, Germany, Italy and Spain.

Other points of contention include the perceived loss of sovereignty from overseas policymakers. In addition, high levels of migration into the U.K. from typically far poorer EU members have raised concerns about loss of jobs to British-born citizens and greater burden on public services.

The prime minister is actually in favor of remaining in the union — as are the majority of Conservative politicians that have publicly expressed a view. However, a sizable minority have come out in favor of a Brexit, including Boris Johnson, the former London Mayor and potential future party leader, and Zac Goldsmith, who failed in his mayoral bid this month.

Earlier this year, Cameron attempted to hammer out a "special status" for the U.K.in the EU that would make continued membership more appealing to the British public. Concessions included setting a minimum time threshold for EU migrants to the U.K. to start claiming social benefits. However, his efforts seemed to do little to assuage the public's concerns.

A handful of politicians in the U.K.'s main opposition Labour Party have come out in favor of a Brexit but the vast majority wishes to remain.

On Friday, Christine Lagarde, the head of the IMF, said Brexit would be costly in both the short- and long-run for the U.K. and that possible outcomes ranged from "pretty bad to very, very bad."

The IMF is set to detail its exact forecasts of the cost to the U.K. on June 16 — just a week ahead of the referendum. Some "leave" campaigners have criticized the IMF and the Bank of England of overstepping their mandates by commenting on what is arguably a domestic political issue.

On Monday, Fitch Ratings warned Brexit would weigh on other EU countries. Economic risks include a reduction in EU exports to the U.K., a decline in the U.K.'s contribution to the EU budget and a fall in the value of financial assets held in the U.K. should sterling depreciate long-term.

Aside from economic risks, there are also political concerns: There could be a shift in EU power towards countries that are more protectionist and less economically liberal than the U.K. plus, if there was a U.K. vote to leave, other countries might look to quit the group.

To learn more about why Norman Lamont thinks the U.K. should leave the EU, click here to read an opinion piece by the former Chancellor.