September is here, which means crisp fall air, pumpkin spice everything — and countless hours of football.

But what if I told you that the more college games you watch this year, the less you'll actually know about who the best teams are?

As it happens, when it comes to predicting success in bowl games, preseason polls are actually a better predictor than end-of-season polls. That means right now, before any games have even been played, the collective wisdom of our sportswriters and coaches is actually better than it will be come November.

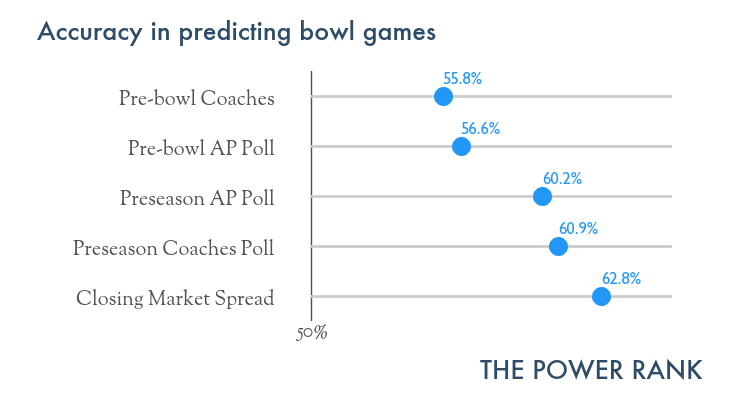

Look at this data from Ed Feng, who runs the sports analytics site The Power Rank. His figures show that forecasts of team success before the season kicks off are more accurate than when it winds down.

It suggests that voters tend to get it right before the first kickoff, relying on instinct and a loose sense of talent, rather than actual game results. It's almost as if actually watching real games fools people into seeing trends that don't really exist. Poll voters are developing an overinflated sense of a team's talent, and expecting a level of performance that might not be sustainable.

(Just for those who don't know: Pre-bowl polls are at the end of the regular season, right before the bowl games start. Closing market spread refers to the betting lines set at gambling houses right before the games kick off.)

It's actually true for college basketball too: The preseason polls do an excellent job of predicting tournament success, and it's just as accurate as using the tournament seeds to pick winners. In many years, the preseason poll has been better at predicting the Final Four than the poll in the final week of the season.

The problem is similar to what happens in the stock market. Traders tend to overreact to things, pushing up stocks too high on good news, or pushing them too far down on bad news. That's why we have trading lingo like "correction" — a move that corrects the value of an asset that was likely inflated in the first place. In other words, it fixes a mistake that shouldn't have been there.

A similar effect reflects what's happening with football and basketball polls. At the beginning of the year, the sports world already has a decent idea of which teams are actually good. That is, until they actually start playing games.

At that point, all the ordinary observers (especially the voters in sports polls) start to see performances we didn't expect, so they start ranking teams in order to "properly" account for who is really the best. Much of these up and down moves, however, are just the week-to-week noise of playing games.

In fact, it largely resembles the daily and weekly volatility of stock prices, which sometimes is a distraction from the fundamentals of the company — which may be better than the fluctuations predict.

By the end of the year, all those football games wash out. Fans would have been better off just ignoring those late-year polls, or really any of the polls along the way. In fact, they may have achieved better results on the whole by simply not watching any games at all. The outcomes of the games can often be more random noise or luck, rather than real proof of who is better.

The first polls of the year are already out — so maybe that's all we need to know.