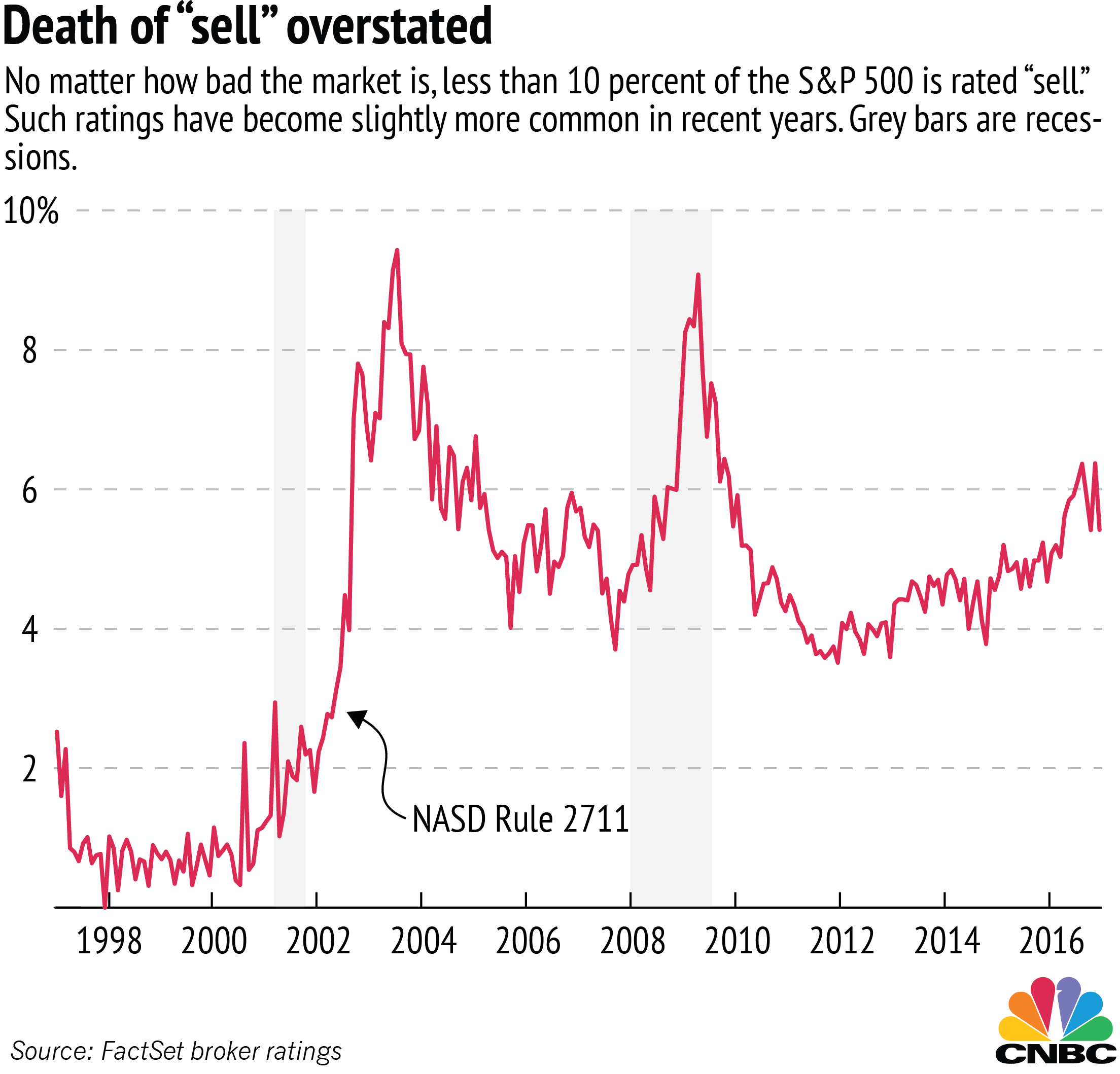

It may seem like Wall Street analysts' stock ratings are growing lopsided in favor of the positive, but the portion of stocks rated "sell" isn't actually a whole lot different from past years, according to a CNBC analysis.

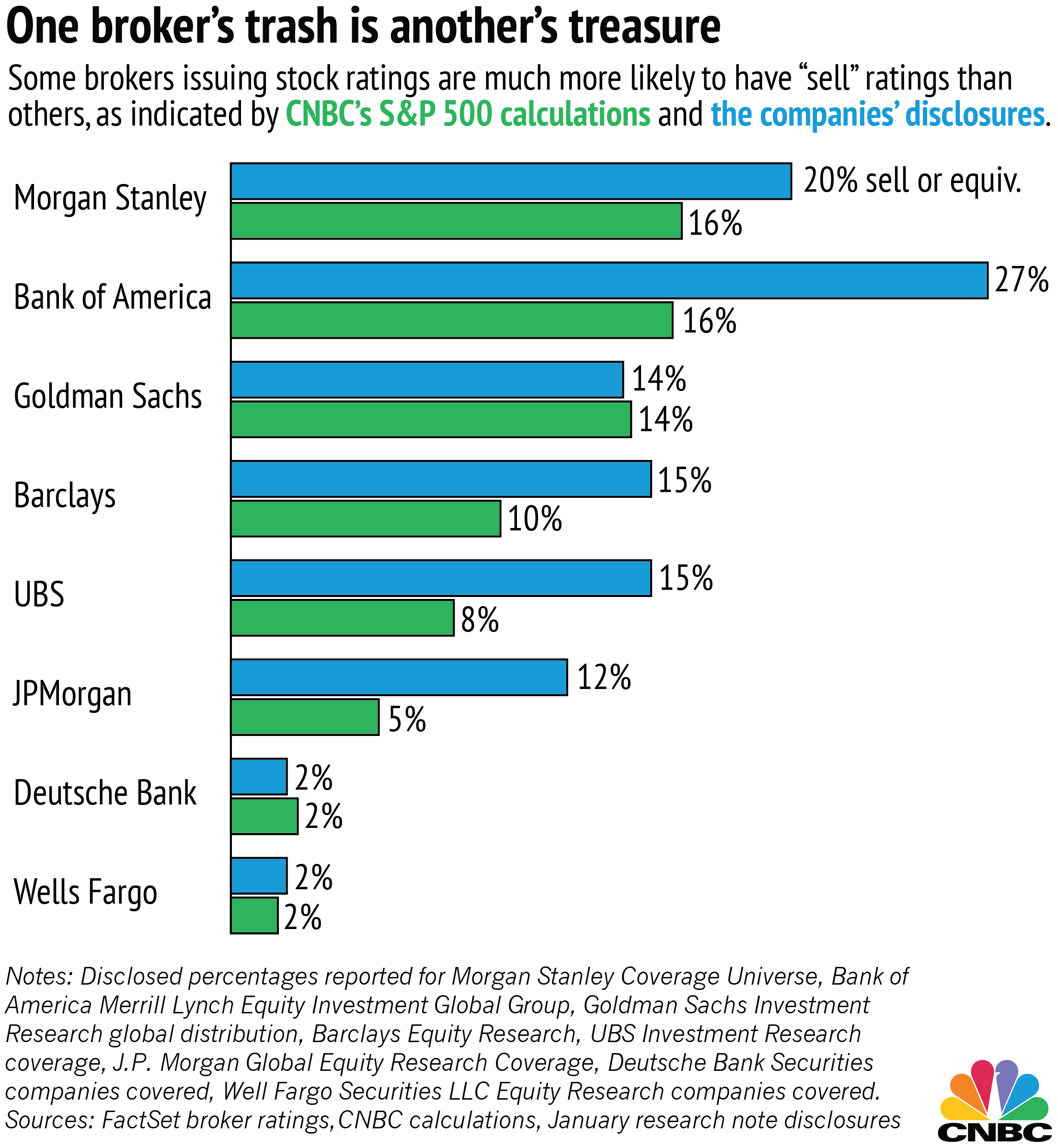

Wall Street researchers are often compensated based in part on their ability to secure investor meetings with corporate management. Some may avoid sell ratings so they can keep those relationships friendly, according to a recent story by the Wall Street Journal. Out of thousands of recommendations tracked by market data provider FactSet for S&P 500 companies, only about 6 percent are sell or "underweight" ratings.

That's a tiny fraction, and yet it's actually the highest percentage we've seen since the Great Recession. Even when the market was crashing, analysts have always rated at least 90 percent of S&P stocks as "buys" or "holds," while recommending investors sell only about five percent of stocks on average.