How long is a fiscal quarter? Maybe you thought it was a quarter of a year, or three months?

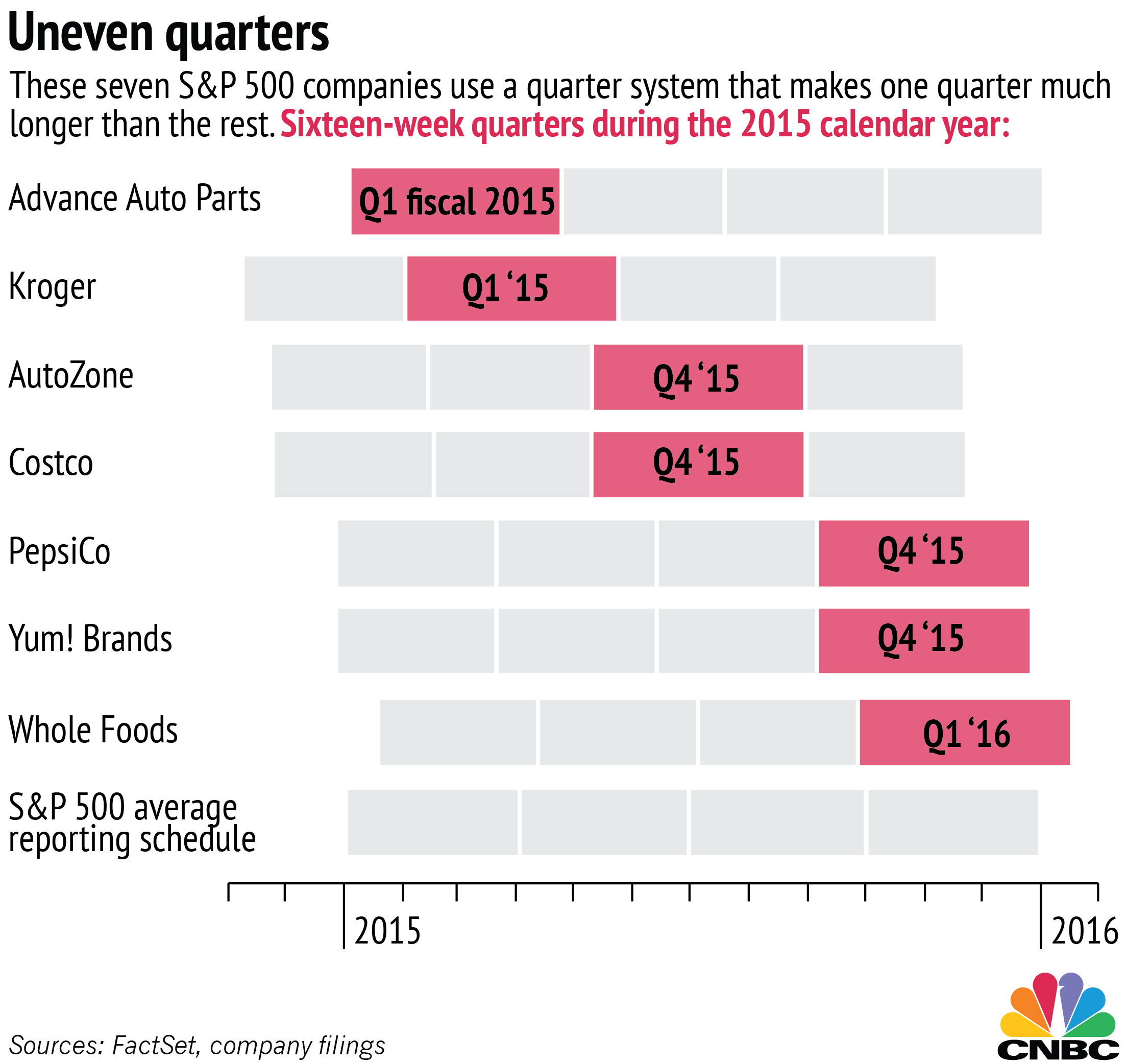

You'd be right most of the time, but for a handful of public companies, that assumption is dead wrong. A few firms, including big names like PepsiCo, Kroger and AutoZone, use a rare reporting system that makes one quarter of each year a full month longer than the rest.

For market watchers comparing companies or attempting seasonal analysis, those dramatically different quarter lengths could throw a wrench in calculations, because one quarter is 33 percent longer. And most people have no idea those long quarters even exist.

"I discovered it totally by accident and said, 'I can't believe this,'" said Martin Gosman, an economics professor at Wesleyan University who has co-written a paper about the long quarters and warns students about them in his classes. "I asked people who have audited and been in public accounting, and they said they'd never heard of it."

There's nothing in SEC rules that says a company can't have uneven quarters, as long as they're consistent year to year. But it is extremely unusual – only seven companies in the S&P 500 use the system, according to a CNBC analysis.