After a weak March, April isn't starting off any better.

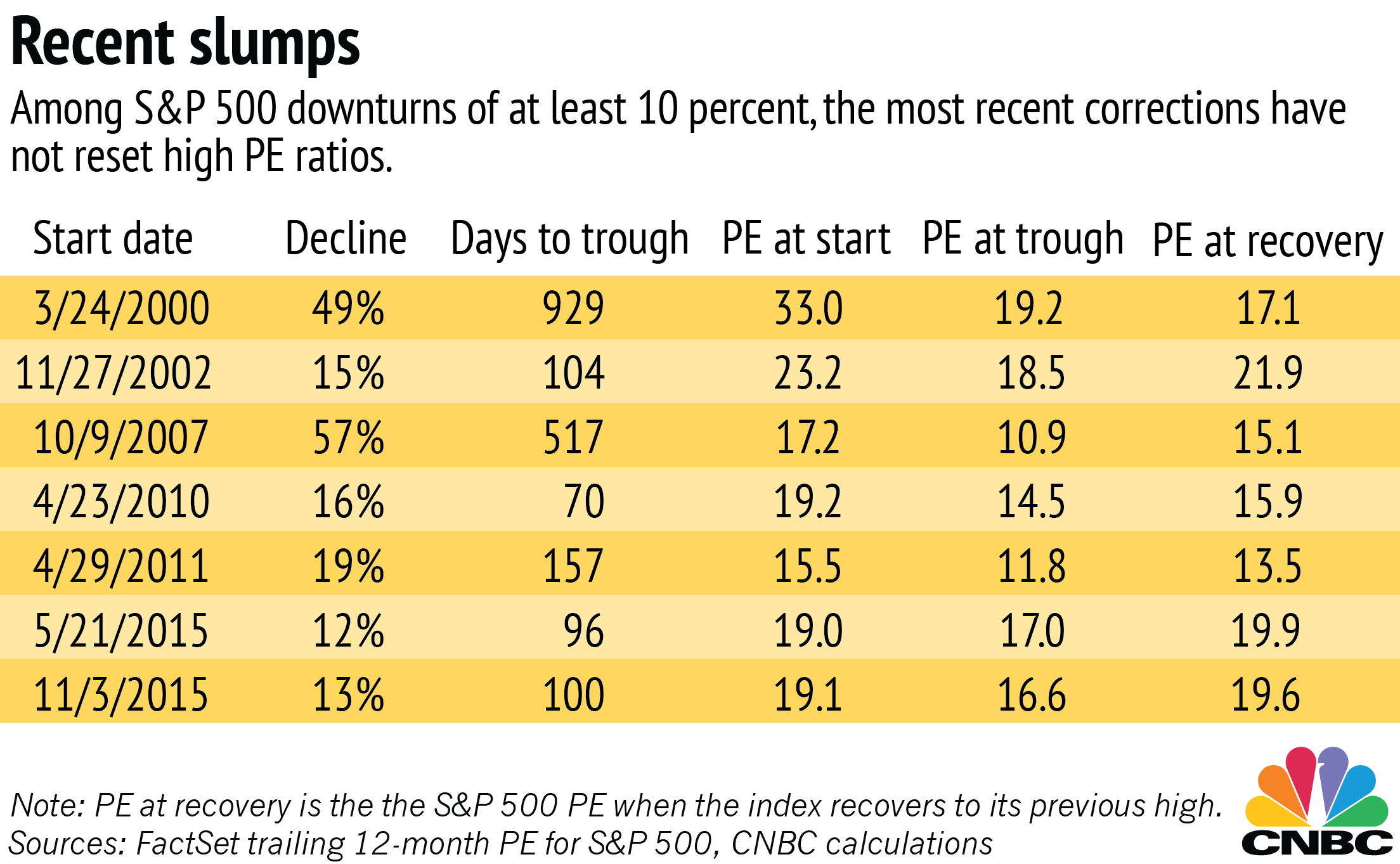

Recent performance is raising the possibility of a market correction that would bring valuations more in line with corporate earnings, and it would take at least a 20 percent decline in the S&P 500 for price-to-earnings ratios to return to their recent averages.

High valuations are just one of many factors that could be signs of a correction in the near future. Analysts have also pointed to falling commodity prices and political disappointments that could usher in a downturn. Other investors are hoping for a correction to keep the market healthy and in line with fundamentals.

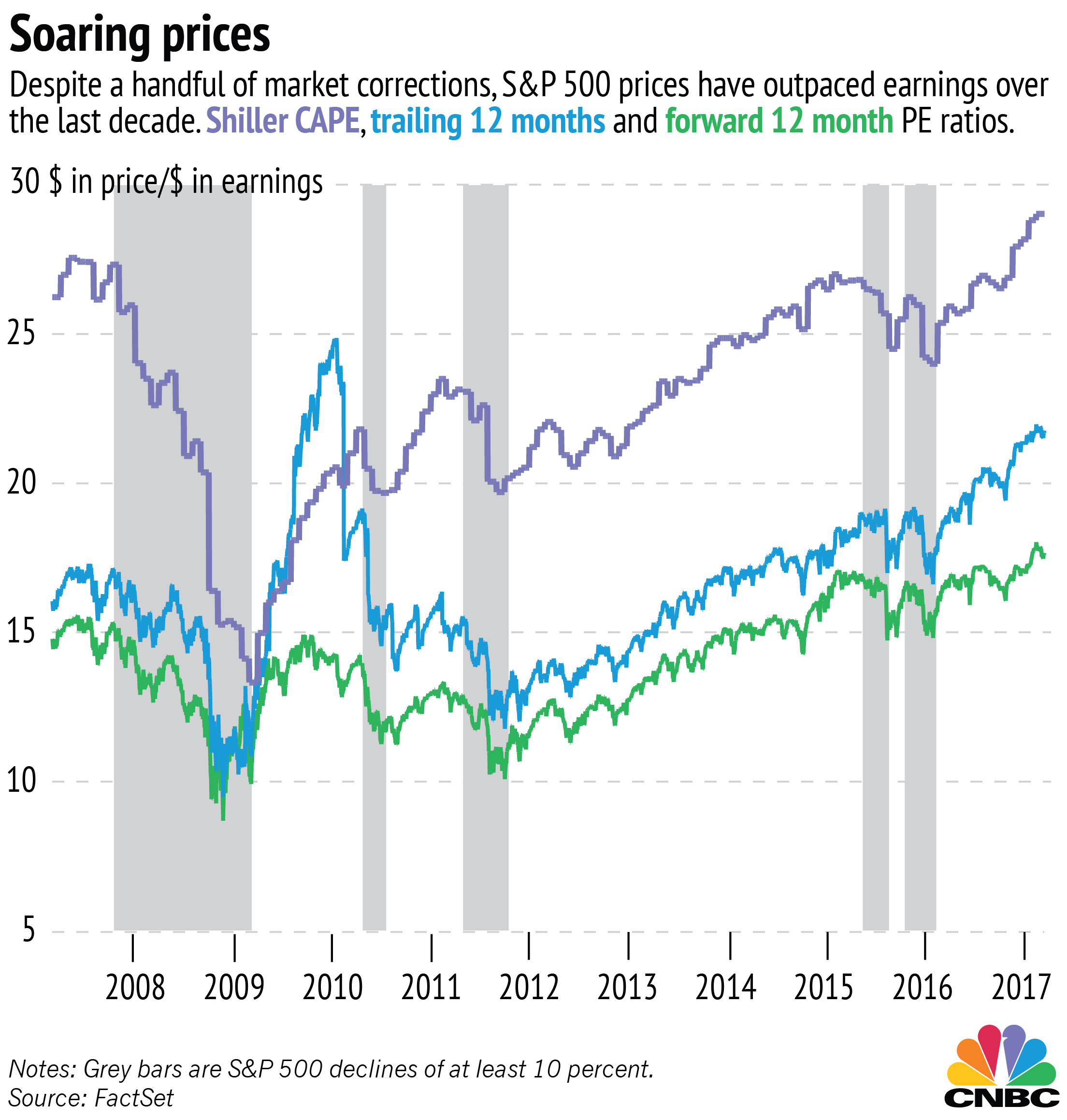

Stock prices are about 22 times more than the last year's earnings, compared with a 10-year average of about 16. The cyclically adjusted price to earnings ratio (CAPE) is near 30, compared with a recent average of about 23. The market has had a number of minor corrections since the Great Recession, but they have done little to slow price gains relative to earnings.