As G-20 finance chiefs from around the world meet on Friday to discuss fears of competitive currency devaluations, policymakers told CNBC that talk of a currency war was misplaced and discussions should instead focus on a how to heal the still fragile global economy.

Talk has focused on the "race to debase" in recent months after a leadership change in Japan, with new Prime Minister Shinzo Abe openly calling for aggressive monetary stimulus from the country's central bank.

France, fearing a strengthening euro and downward pressure to export competitiveness brought up the topic at a meeting of finance ministers on Monday.

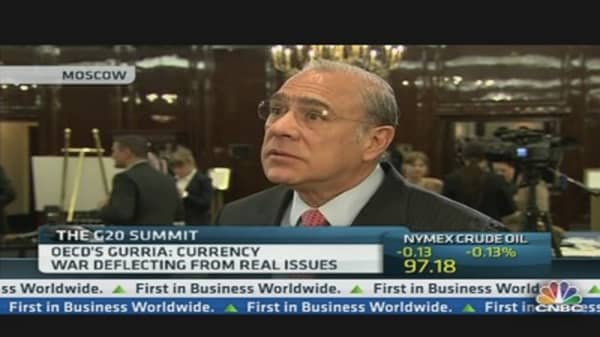

Many expected more of the same at Friday's meeting of finance ministers and central bankers in Moscow, but Angel Gurria, secretary general at the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development dismissed the idea.

"I don't think we should be losing any time in talking about the currency wars," he told CNBC Friday in Moscow.

"There is no currency wars, we are furthest away today from a currency war than we were two or three years ago."

(Read More: Currency Wars Come to Moscow as G-20 Meets)

The currency war phrase, coined in 2010 by Brazilian Finance Minister Guido Mantega, is no longer relevant, according to Gurria. He said such jargon should be resigned to the past.

"We're fighting an old war. Today we should be concentrating on productivity, be concentrating on competitiveness and we're being distracted by this currency discussion," he said.

Leaders from the G-7 group of industrialized nations released a statement on Tuesday reaffirming their longstanding commitment to market-determined exchange rates. But, shortly afterwards confusion reigned as reports emerged that an unidentified G-7 official was quoted as saying the statement had been "misinterpreted" and was instead a warning shot for Japan.

(Read More: Currency Wars or Just Currency Confusion?)

"It's very important to avoid loose talk about currencies," Lael Brainard, the U.S. treasury undersecretary for international affairs, told CNBC in Moscow.

"The G-7's statement earlier this week was very important, it made clear that the G-7 remains committed to market-determined exchange rates but it also talked about how important it is and how committed we are in ensuring that monetary and fiscal policy remain oriented toward domestic objectives."

The G-20 nations have an obligation to run their exchange rate regimes in a way that's compatible with growth globally, she said, adding that they must come together and strengthen global demand.

But the confusion apparent in the G-7's statement could linger. The new managing director of the International Institute of Finance (IIF), Timothy Adams told CNBC there is a "message void" coming from the policy makers.

"They've got to focus on growth, everyone recognizes after looking at fourth-quarter data [in the euro zone] that, years into this crisis, recovery is fragile at best. Ministers and central bankers are going to have to look around the table and ask what are we doing wrong and right to tackle this slow growth environment," he told CNBC Friday in Moscow.

"That's why we need a cooperative spirit coming out of Moscow this weekend."

Jacob Frenkel, international chairman at JPMorgan Chase and former governor at the Bank of Israel, warned of an escalation of aggressive exchange rate policies.

"Each country wants to find a mechanism to stimulate their demand for each product since domestically their policies have already exhausted their capabilities," he told CNBC, suggesting that monetary and fiscal policy had been exhausted by most nations.

Instead, countries will look to increase overseas demand for their exports goods by devaluing their currencies, he said.

"But if each one of us tries to depreciate our currency, the currency basically does not regain competitiveness," he said.

"We are all going into a direction of, first, adversarial relationships and, finally, maybe an inflationary pressure in the pipeline. This is the danger of the currency war, that needs to be really avoided at all cost."

The yen has tumbled in value since the Bank of Japan doubled its inflation target to 2 percent in January, and made an open-ended commitment to continue buying assets next year. And since the leadership change in November and this new dovish attitude to monetary policy, the yen has depreciated around 25 percent against the euro.

Fingers may have been pointed at the Japanese since this fall but the IIF's Adams said it was important to remember that Japan has been dealing with 18 years of deflationary pressures.

"They should deal with that and we should be supportive [but] the key is to not target the exchange rate and maybe just stop talking about exchange rates generally," he said.

(Read More: Currency Wars Return, 1930s Style: Who Will Lose Out?)

Others also backed Japan, with Darmin Nasution, governor of the Bank of Indonesia telling CNBC that countries should have a policy mix and any quantitative easing is not directly linked to the depreciation of nations' currencies.

Daniel Mminele, deputy governor of the South African Reserve Bank was also quick to dissolve any blame at one particular nation.

"Some of these consequences you can't always work out and foresee in advance," he told CNBC Friday.

Each nation has to be in constant conversation with partners with other policy makers, he said, and make sure that policy doesn't end up affecting others adversely and lead to a feeling that there could be a need to retaliate.

—By CNBC.com's Matt Clinch, additional contribution by Holly Ellyatt