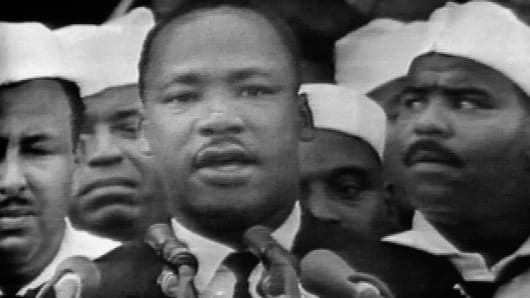

Fifty years to the day that Rev. Martin Luther King told a crowd of 250,000 in Washington that "the Negro … finds himself an exile in his own land," Wall Street is mostly a foreign country for black workers.

The difficult road that blacks still face in the heart of America's financial capital was underscored by news Wednesday that brokerage giant Merrill Lynch has agreed to pay $160 million to settle racial discrimination claims by black brokers.

Despite what would be the biggest race-discrimination lawsuit payout ever by a U.S. employer, King's dream remains just that for African-Americans trying to get hired, promoted and paid well in the financial industry.

A lawyer for the 700 brokers who sued the firm eight years ago said Merrill's alleged pattern of underhiring black brokers and practices of allocating customers that allegedly made it more difficult for those brokers to build business are not unique.

"They filed this lawsuit for all the right reasons," said Suzanne Bish of Chicago-based Stowell & Friedman. "To not only change Merrill Lynch, but also to change Wall Street. It was not an issue that was limited to the Merrill Lynch, the underemployment of African-Americans and revolving doors of African-Americans."

Her firm had previously filed and ultimately resolved a class-action lawsuit on behalf of female employees claiming sex discrimination by Merrill Lynch.

When Merrill broker George McReynolds retained Stowell & Friedman to sue for race discrimination, Bish said, "we were kind of stunned to realize the predicaments for African-American financial advisors was even worse."

Bill Halldin, a spokesman for Merrill Lynch, declined to comment when asked to confirm the settlement's being reached or the $160 million figure.

"We are working toward a very positive resolution of a lawsuit filed in 2005 and enhancing opportunities for African-American financial advisors," he said.