As the fight to end the latest Ebola outbreak rages on, concerns are mounting over whether the deadly disease will become a global contagion.

The World Health Organization estimates that Ebola has already killed more than 4,400 people in West Africa and infected at least twice that many.

Cases outside the region have also surfaced: A nurse in Spain contracted the virus, and the first person diagnosed in the U.S. died in Dallas last week. Two health-care workers in Texas who treated the patient have tested positive for the virus.

At the same time, the economic cost associated with the epidemic is spiraling: A report from the World Bank said it could reach $32.6 billion by the end of 2015 if the disease spreads from Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone to neighboring countries.

While health officials say they're making progress against the spread of Ebola, there are questions if the right medicines and screening procedures were in place—and if new cases will be handled differently.

Read MoreEbola could reach France and UK by end of October: Scientists

"They were three months behind from the start in fighting this," said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician at the University of Pittsburgh.

"But they didn't have this type of outbreak before in these countries, and they underestimated how far behind the health systems in these areas were," he added.

"I think the Centers for Disease Control has done a good job, but we can do more in the future," said Dr. Pascal James Imperato, dean of the school of public health at SUNY Downstate Medical Center.

"Had they weighed the history of Liberia and that the man who was the first case in the U.S. came from there, they might have jumped on this sooner," he said.

Hospitals doing enough?

Beyond specific vaccines and treatments—which have so far proved elusive for Ebola—challenges exist on how medical facilities are properly prepared to handle cases.

The hospital in Dallas that dealt with the first diagnosis of Ebola in the U.S has come under scrutiny.

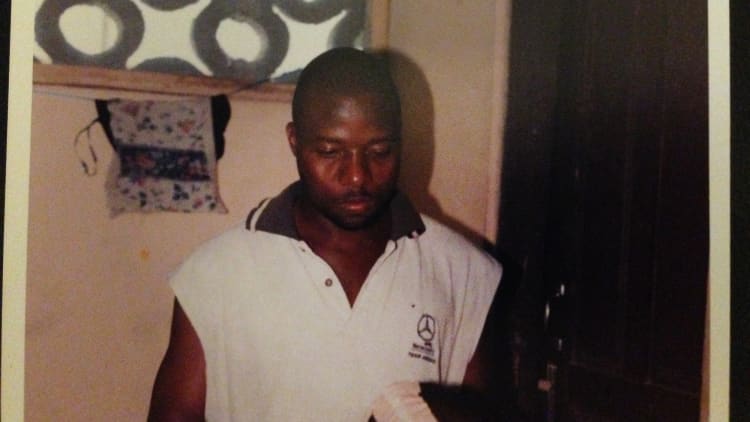

"The medical case of Thomas Eric Duncan should serve as a reminder to hospitals to verify that their electronic medical-record systems and procedures for handling infectious diseases are in place," said David Walsh, a health-care lawyer at the Dallas firm of Chamblee, Ryan, Kershaw & Anderson.

Roslyne Schulman is director of policy at the American Hospital Association and said that the nation's hospitals are prepared for Ebola cases.

"Every hospital can isolate and give initial care to an Ebola patient," she said. "We've been urging hospitals to follow CDC guidelines on setting up private rooms and private bathrooms for patients."

Other experts aren't so sure everything's in place.

"Despite all the insurances we've had about how prepared the U.S. is to handle more Ebola cases, I haven't heard anyone from the media ask how many hospital beds are available for potential patients," said John Palisano, professor of biology at Sewanee: The University of the South.

Read MoreCDC to announce new Ebola screening measures

Angela Vassallo, director of infection prevention and an epidemiologist at Providence Saint John's Health Center in Santa Monica, California, expressed assurance about the health-care system.

"Humans are not perfect, but I am confident we are getting ready for any outbreak," she said.

To test the point at her medical facility, Vassallo said she recently went undercover through her hospital's ER protocol to see if the right procedures were followed by the staff for someone who might have Ebola.

"They did everything right, including putting me in an isolation room," she said.

Big pharma's role

Many experts credit groups like the World Health Organization, government entities like the Centers for Disease Control and nonprofit entities like Doctors Without Borders for making good-faith efforts to handle epidemics.

However, the pharmaceutical industry has come under fire for not doing enough when it comes to finding treatments.

"Over the last 15 years, big pharma has pulled away from developing new drugs because of the expense and time involved," said Guy Macdonald, CEO of Tetraphase, a smaller pharmaceutical firm that is developing treatments for antibiotic infections.

Tetraphase has gotten funding from the U.S. government in its efforts, but Macdonald said there needs to be even more teamwork between the public and private sector.

Read MoreFast-tracking an Ebola vaccine may prove too slow

Dr. David Vaughn, head of GlaxoSmithKline's external research and development, North America, admitted that the development cost and time it takes to get a drug on the market—anywhere from six to eight years—has pushed the bigger pharmaceutical firms away.

But GSK and the National Institutes of Health have recently partnered on an Ebola vaccine that has entered Phase 1 clinical trials.

"We got approval to get the process going within 48 hours from the Federal Drug Administration when it normally takes 30 days," said Vaughn.

Vaughn couldn't say when the vaccine might be available for general use but said that GlaxoSmithKline is "going as quickly as we can without compromising the safety" of the vaccine.

Read MoreBudget cuts are NOT why there's no Ebola vaccine

But don't expect the medical community to find a cure-all, said University of Pittsburgh's Adalja.

"We have new viruses that appear and disappear and mutate, so we can never be fully prepared with drugs and vaccines," he said.

Family and business

With science unable to eradicate many diseases, the home front needs to be part of the fight, said Dr. Cecilia Rokusek, assistant dean for education, planning and research at Nova Southeastern University's College of Osteopathic Medicine.

"We have to constantly keep in the minds of people the need for good hygiene, like washing hands, getting immunizations and other healthy habits," Rokusek said.

"But If you asked a family if they were prepared in an emergency, would they be ready? I think the answer is no," she argued.

Armistead Whitney is CEO of Preparis, which provides emergency planning solutions to its clients. He said the business community must also step up for any future health crisis.

"Many executives are talking about pandemics now and what they need to do," he said. "But many businesses still think it doesn't apply to them."

Whitney said companies should have updated contingency plans in place for employees during any medical emergency.

That includes systems to work at home and payroll structures to ensure employees can get paid if there's a longtime absence. It also means setting up protocols for employees traveling overseas during outbreaks and knowing which countries might need to be sidestepped.

Travel restrictions

As for calls for travel restrictions to and from West Africa, the director of the CDC, Tom Frieden, has said that a travel ban could hurt Americans in the long run by limiting the ability of relief workers and supplies to get into West Africa's Ebola zone.

But medical doctor and psychiatrist Carole Lieberman said not enough is being done on that point.

"Ebola can spread to the U.S. more easily than people want to believe, because travelers in Africa can bring it back to American soil," Lieberman said. "Whatever protective measures are currently in place are not at all foolproof."

Lessons from Spanish flu

One of the more chronicled global pandemics of the past may be an example of dos and don'ts.

The Spanish flu outbreak, which lasted from 1918 to 1920, left at least 50 million people dead. Nancy Bristow is professor of history at the University of Puget Sound and has written a book on the topic.

Bristow said It was a time when most people thought science had contagious diseases under control, only to be proved wrong. One big mistake health officials made during the outbreak was not balancing protection with panic.

"They were so concerned about the hysteria around it that they didn't put in place efforts to help," Barstow explained. "That included shutting down schools, placing people in quarantines and doing something as simple as keeping windows open to let fresh air in."

Bristow added that unlike today, there was no true government oversight in the U.S. to handle the situation, leaving communities on their own.

"The city of Milwaukee was a case where they handled it right by implementing strict rules on public contact, but a city like Pittsburgh did not, and they had many more cases," she said.

Bristow added that the pandemic energized the scientific community to do more study on contagious diseases—including current work on the virus that caused the Spanish flu outbreak.

Another wake-up call

Ebola has broken out at various times since 1976. But this latest round has far surpassed the number of deaths of any previous outbreak.

Some of the reasons cited for the devastating spread include cultural differences in West Africa, such as not trusting government officials and burial practices that allow for touching the bodies of victims.

"We have to break down some of these barriers that keep people from getting well," said Dr. Gerald Parker,vice president for public health preparedness and response a the Texas A&M Health Science Center.

Deeper-seated issues, say experts, include lack of fresh water and inadequate health care in countries suffering from economic setbacks and a growing population.

"We also have to more than just open up our hearts," Parker added. "We need committed partners in the international community to provide help for people who are suffering."

Dr. Robert Quigley, U.S. medical director and senior vice president of medical assistance for International SOS said the world has a tendency to ignore the lessons of the last epidemic.

"These kinds of diseases should serve as wake-up calls to update our systems and to review plans of preparation," he said. "But we tend to go back to our complacency."

For the University of Puget Sound's Barstow, countries like the U.S. must take a global view whenever the next pandemic of any kind strikes.

"We have to treat each other as citizens of the world," she said. "I worry that we don't do that."