These days, a pension just isn't what it used to be.

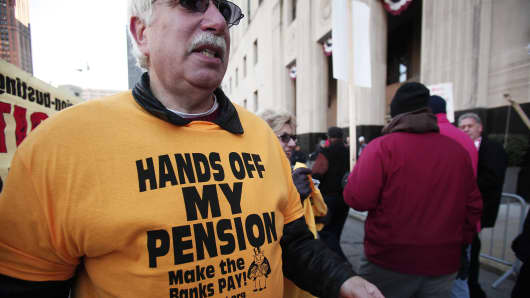

For generations, a defined benefit pension—a fixed monthly check for life—provided an ironclad promise of a secure income for millions of retired American workers. But today, that promise has been badly corroded by decades of underfunding that have undermined what was one of the cornerstones of the American dream.

The safety net that millions of retirees spent decades working toward has been fraying for some time. The Great Recession, and the market collapse that wiped out trillions of dollars of investment wealth, weakened the pension system further, though some of the damage has been repaired since the stock market rebounded and the economic recovery took hold.

Hundreds of billions of dollars in defined benefits are still paid out every year to retirees. State and local public pension benefit payments reached $242.9 billion in 2013, according to the most recent Annual Survey of Public Pensions. And a Towers Watson study of more than 400 major companies that sponsor U.S. defined benefit plans estimated they paid out nearly $97 billion in benefit payments last year, and another $8.6 billion went toward lump sum payments and annuities.

But that's nothing compared to the private employers' projected benefit obligations last year, which climbed 15 percent from the previous year to a whopping $1.75 trillion, while plan assets grew by only 3 percent.

Disparities like that help explain why so many pensions are in peril. Simply put: Obligations have outpaced fund contributions and growth for private and public plans. That means that even workers who have paid into pensions for several years may not get the level of benefits they expect. And many younger employees may never have an opportunity to participate in a pension at all.

The result is that, unlike past generations of Americans, many workers today bear the brunt of the investment risk that underpins their hopes of income security once they are no longer able to work.