Amazon's earnings generated a bad market reaction, but it could have been worse.

Stock in the online retailer fell 9 percent in after-hours trading last Thursday after the company reported net income of $1 a share, missing estimates of $1.56. But it likely could have been worse if the company had delayed reporting its earnings.

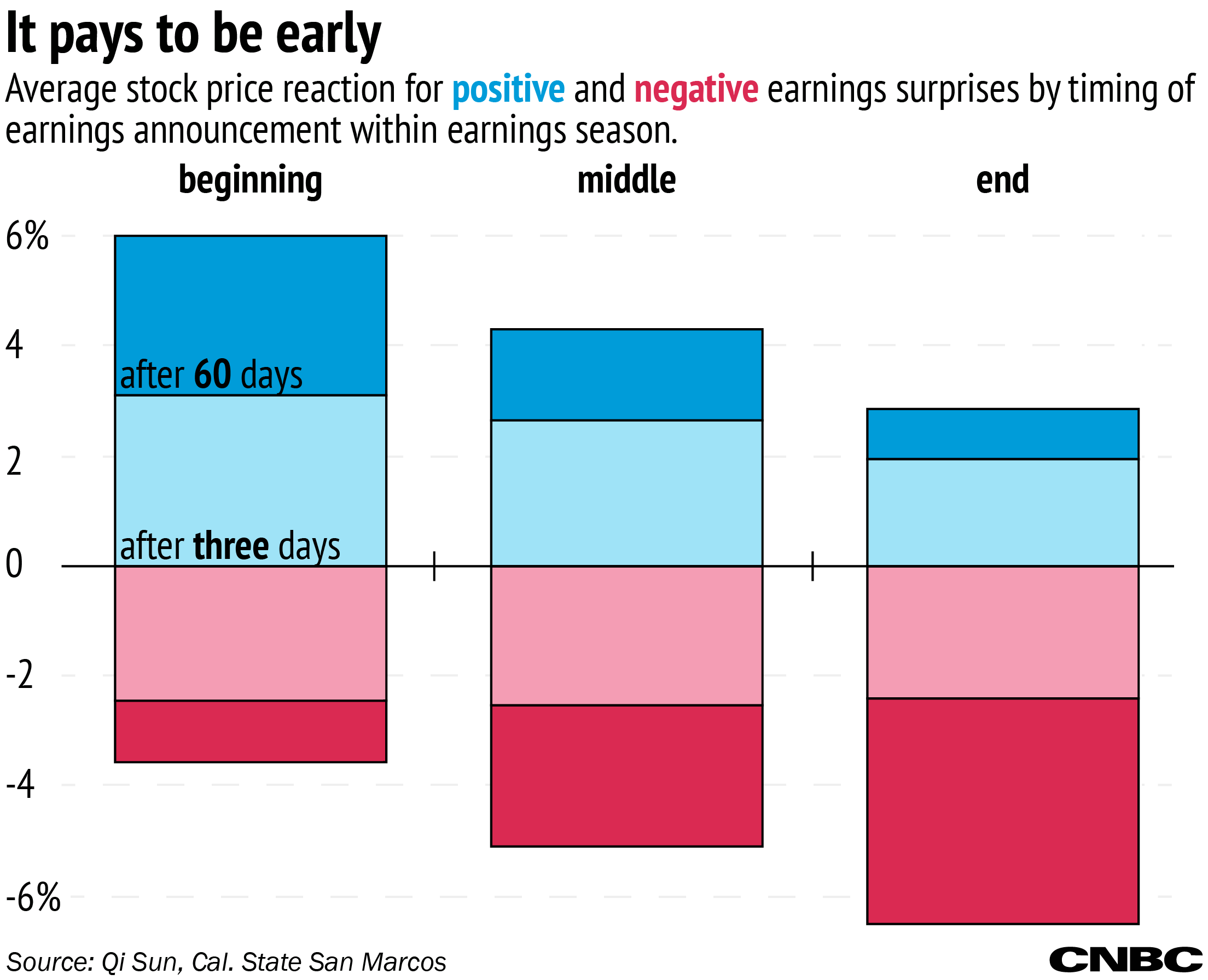

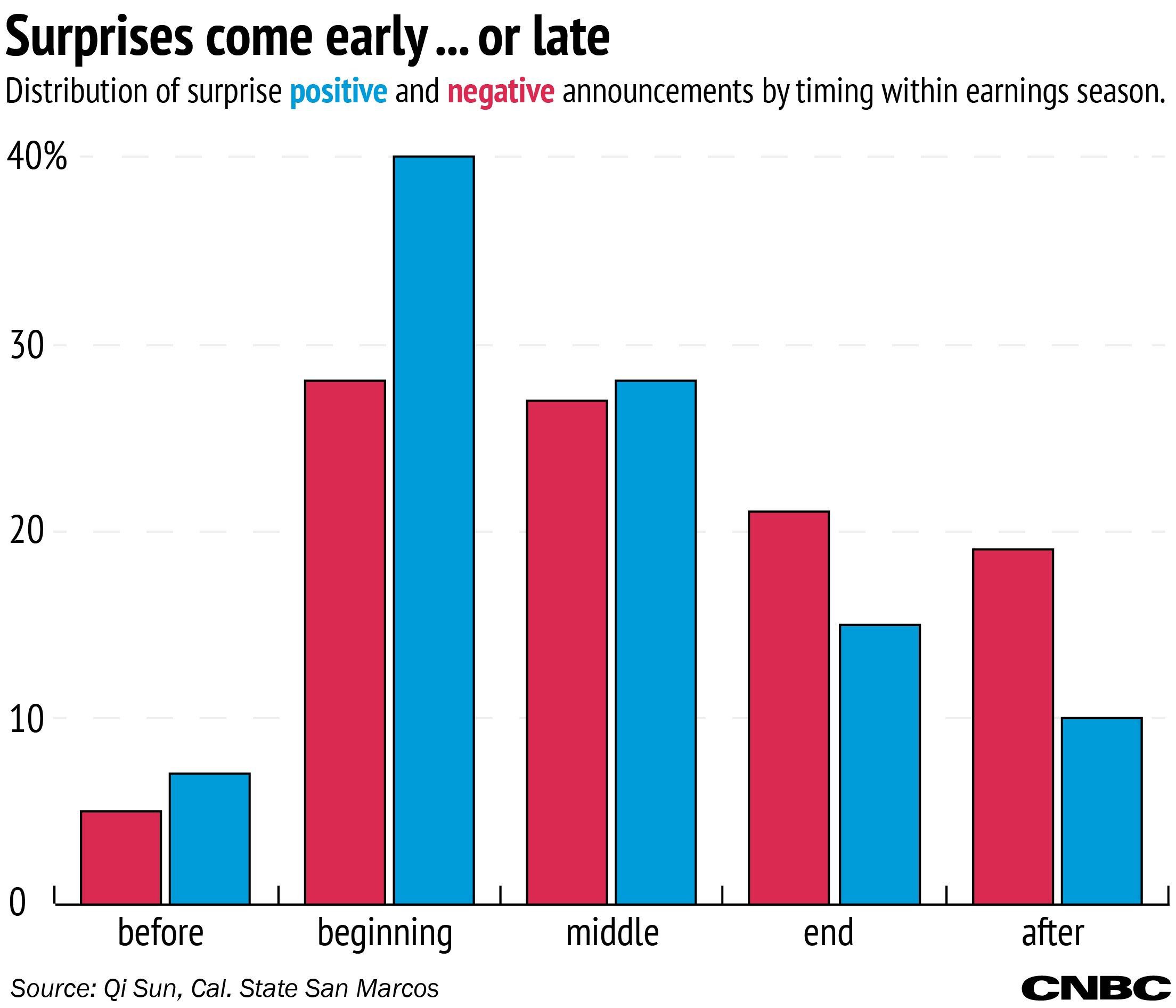

Research from California State University, San Marcos shows that companies see their stock price fall farther and faster if they delay delivering negative earnings surprise announcements toward the end of earnings season. Likewise, companies beating estimates with surprise earnings see greater return when they report at the beginning of earnings season.

So if you have bad news to tell your investors, it's best to get ahead of the game and come out to tell them. Delaying the inevitable just makes you look shady and won't do them any favors in the long run.