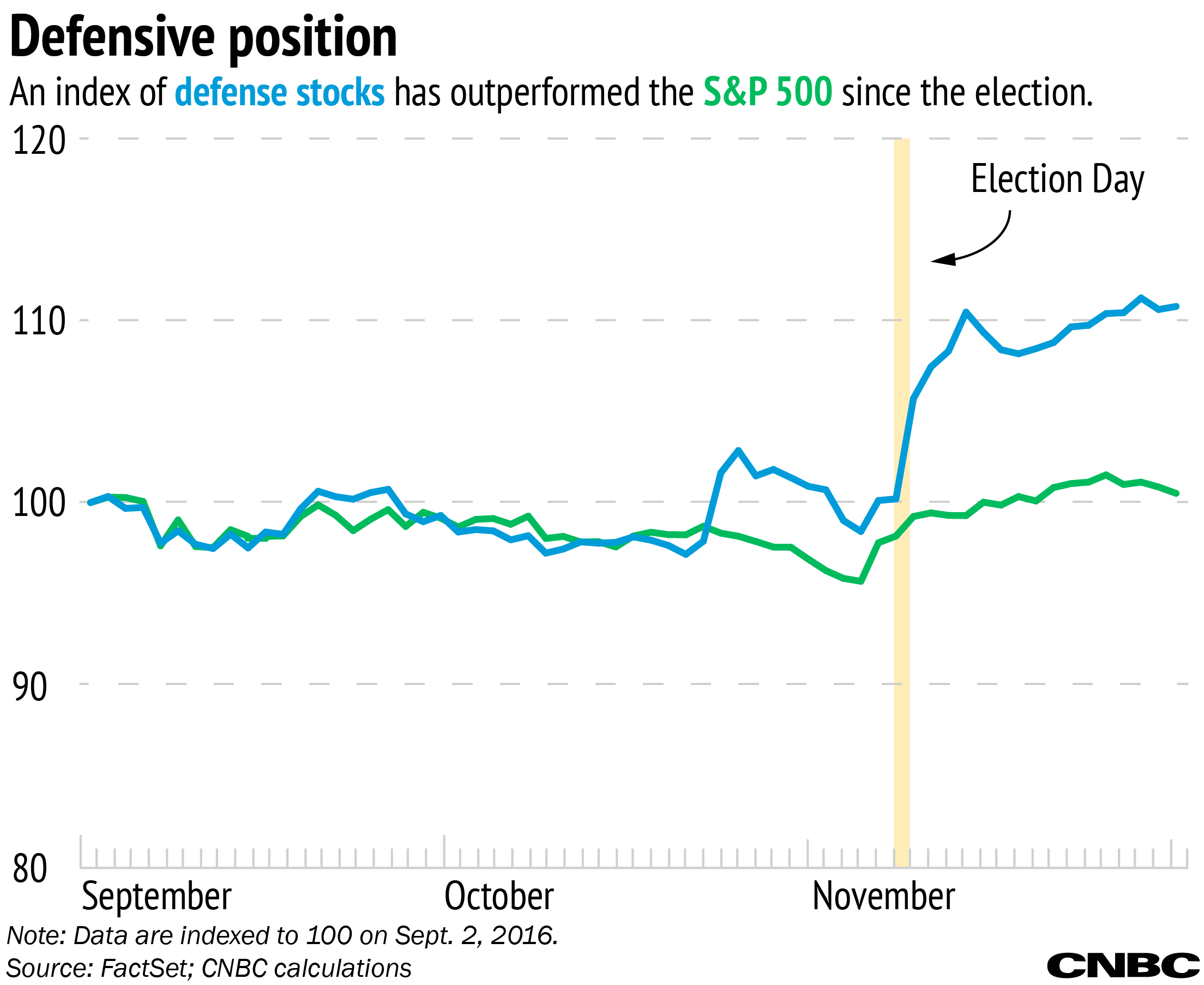

At first, Donald Trump's election had the market buying up defense contractor stocks, but the Carrier deal has led some to wonder whether those companies might actually face rising scrutiny from the new administration.

Trump was involved in negotiating an agreement to keep about 1,000 jobs in Indiana in exchange for $7 million in tax incentives from the state over 10 years. But it was actually fear that Carrier's parent company might lose its contracts with the federal government that sealed the deal, John Mutz, a former Indiana lieutenant governor who sits on the board that offered the tax breaks, told Politico and others.

United Technologies, which owns Carrier, did not immediately respond to CNBC's requests for comment.

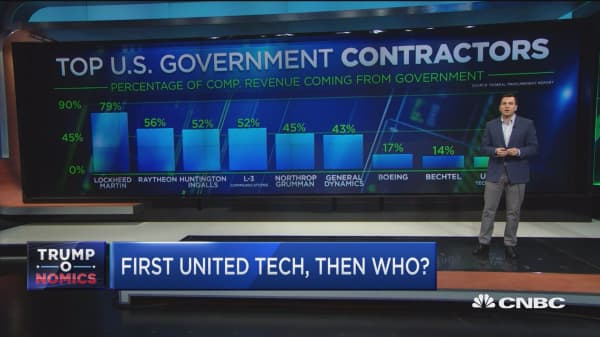

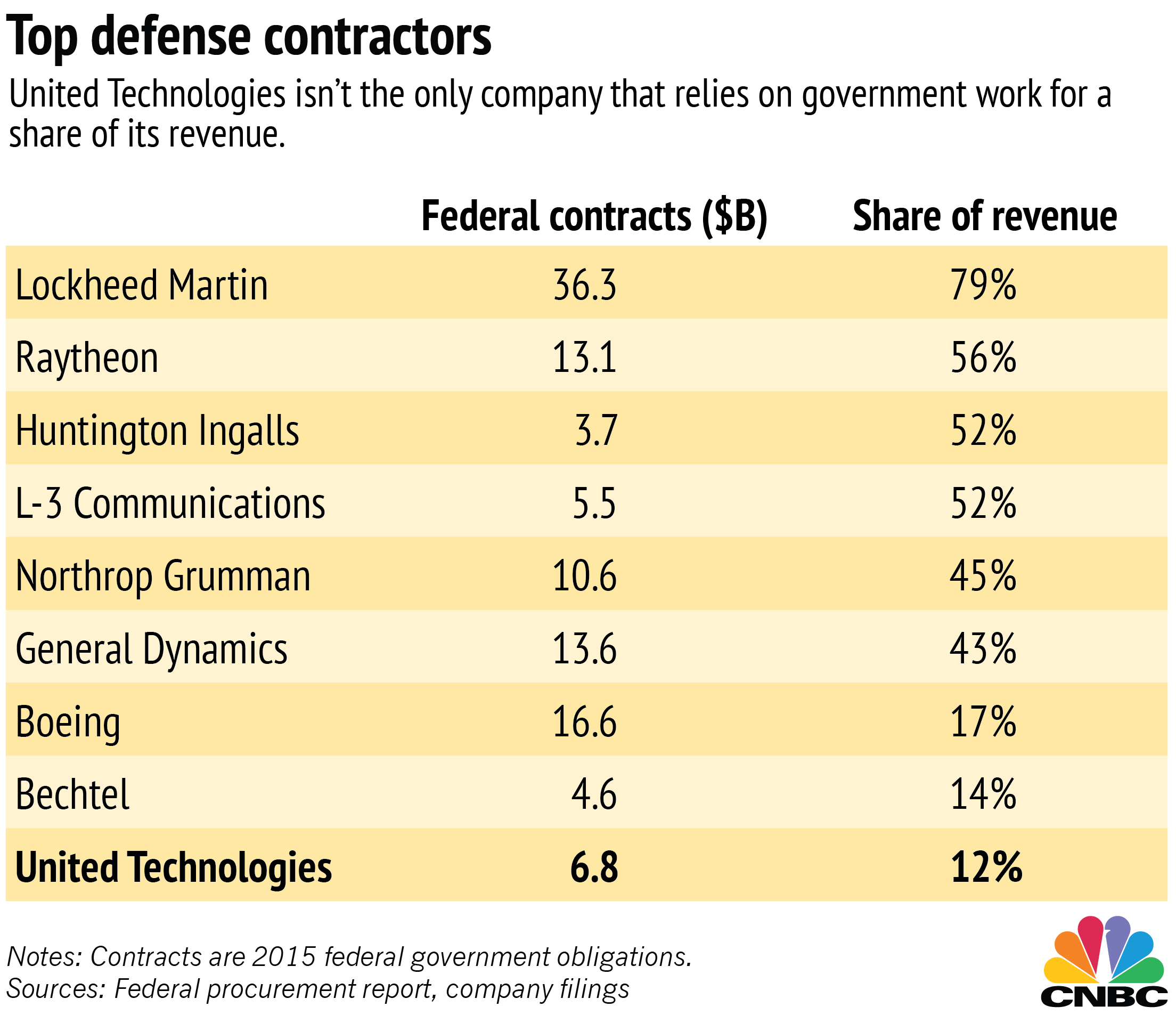

In addition to selling air conditioners to U.S. homeowners, United Technologies also sells billions in jet engines, helicopter components and many other goods and services to the federal government. Those transactions amount to about 12 percent of the company's annual revenue. And that's on the small side — some other big defense contractors rely on government contracts for more than half their sales.