Where were you the day of the crash?

I was on the Hill and obviously I had been monitoring this very closely with intense focus over the previous two weeks. I was getting increasiningly concerned. I had sent a letter to the SEC chairman and asked for a study of 91-point decline on Oct. 6....On Oct. 15. I sent another letter about the big decline the day before. (Click here to read the original letters.)

(What had happened in the runup to it. On July 23, I held a hearing on program trading. The chairmen of the Securities & Exchange Commission, the Commodies Futures Trading Commission, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. The Chicago Board of Trade, The New Yorjk Stock Exchange all testifed. They each said it was not a problem and there was no reason to worry.)

What actions did you take?

I flew up to New York and went to the NYSE. Someone told me to check what was going on in the QT (questionable trade) room. The NYSE was reluctant to let me see it, but I was in the midst of an investigation. Dick Grasso took me down to look at the QT room and in this room were all these traders who were fighting over the questionable trades. All this paper was on the floor, obviously a chaotic condition. It took me three years to finish the investigation. On Oct 16, 1990, President Bush signed legislation for proper oversight and coordination of program trading.

So what caused the crash?

Program trading was the principal cause. There was an obviously a problem in the coordination with the CFTC and SEC. The SEC didn’t have proper emergency authority, there wasn't proper clearing and settlement.

Can it happen again?

I think we gave the SEC the authority it needed in order to put in place the proper safeguard, to allow cooperative working agreements, to reduce significantly the likeliehood of a repetition of that kind of event. What happened back then to a certain extent was a technical problem, a serious technical deficiency.

What's different today about communication?

I think it is a lot more sophisticated today than it was then.

What about investing?

You look at the dotcom bust, the subprime stuff, human nature stays the same. It doesn’t change.

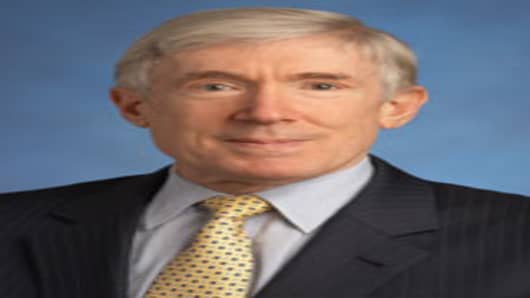

John C. Bogle

Bogle founded The Vanguard Group in 1974 and served as Chairman and CEO until 1996. In 1975, he created the Vanguard 500 Index Fund, the first index mutual fund. Bogle is the author of five books. He was born six months before the stock market crash of 1929. He is currently President of Vanguard's Bogle Financial Markets Research Center.