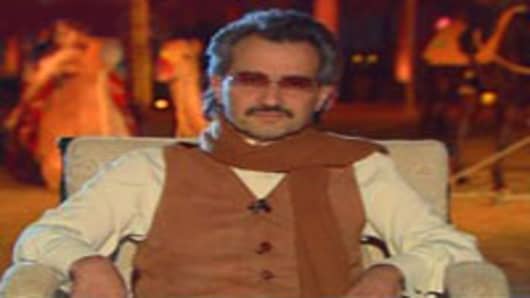

LONDON — The bad news arrived by telephone early this week at the Saudi headquarters of Prince Walid bin Talal.

Citigroup, the investment that had transformed Prince Walid from an obscure Arabian royal into the Warren E. Buffett of the Middle East, was spiraling down around him.

And now, on the line from New York, was Citigroup’s chief executive, calling personally to tell the prince that the United States government would substantially increase its stake in the troubled financial company — a step that would cost the prince dearly. As it did Friday.

The stunning collapse of Citigroup’s share price, to a mere $1.50 on Friday from a record $55 in 2006, has hurt investors worldwide. But few reputations have suffered as severe a blow as that of Prince Walid, who owns about 4 percent of the company.

In its third attempt to stabilize Citigroup, the government announced Friday that it would increase its ownership stake to as much as 36 percent by converting part of its large preferred investment stake to common stock.

Other preferred stockholders could own a 38 percent stake of the bank if they all convert their shares. That would dilute existing common shareholders, who together would now own just 26 percent of the bank.

Those investors include Prince Walid, who injected close to $600 million into Citigroup’s predecessor, Citibank, when it was foundering in 1991.

At the time, the price of $10 — $2.98, adjusted for stock splits — seemed a bargain.

But Prince Walid and several other investors from the Middle East and Asia, including the Abu Dhabi investment fund, are now suffering the public embarrassment of seeing their investments in Citigroup evaporate.

With their ties to the royal families of their respective countries — Prince Walid is the grandson of Saudi Arabia’s founding king, Abdul-Aziz Ibn Saud, and the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority invests the surplus cash of Abu Dhabi’s kingdom — these two investors are among the world’s most influential.

Now they must decide whether to lose their preferred investor status and join the investor rank and file as common equity holders alongside the United States government.

Prince Walid, like other large holders of preferred shares like the government of Singapore, has said he will exchange his preferred stock for common shares.

But the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority has not agreed to the deal and is looking to solicit a legal opinion to assess its options, people briefed on the fund’s thinking said.

A spokesman for the fund declined to comment.

That the investment authority finds itself in such a position is not without irony.

When Abu Dhabi invested in Citigroup, an uproar was raised that this stake represented the first stage of a creeping influence by government-owned investment funds over American financial companies.

Now, it is the United States government that is, in effect, taking over, leaving Abu Dhabi and other foreign investors in a lurch.

Indeed, if the Abu Dhabi fund were to convert its shares, it would forgo the 11 percent interest it is now paid quarterly and lose dependable cash flow at a time — with oil prices low and its neighboring emirate Dubai in a dire economic condition — when the demands for capital at home have never been higher.

For Prince Walid, the developments at Citigroup are a stinging embarrassment.

In November, he made a public splash by increasing his Citigroup stake, thus becoming its largest shareholder when the government carried out its second financial rescue.

Asked in an interview on CNBC if he could foresee Citigroup requiring additional government money, and if he would invest again, the prince responded with his typical flair.

“I believe this is a very far- fetched situation,” he said, saying that in his many conversations with “Mr. Vikram,” as he called Vikram S. Pandit, Citigroup’s chief executive, he had been assured that the bank would have enough capital for the next 12 to 18 months. “This is cherry on the cream and we will take it.”

Prince Walid could not be reached for additional comment.

As befitting his status as a Citibank savior, the prince has received special investor care. For many top Citigroup executives, a ritual pilgrimage to see him was expected.

Sanford I. Weill, who created today’s fallen colossus, was a frequent visitor to the prince’s tent in the desert. His successor, Charles O. Prince III, as well as his recently departed chairman, Robert E. Rubin, also met with the prince frequently.

Early this week, Mr. Pandit phoned Prince Walid to propose that he convert his preferred stock — which would no longer pay a dividend — to common.

After speaking for a few minutes, the two put their top lieutenants on to discuss the confidential details, people close to the situation said.

From Citigroup’s Park Avenue offices, Gary L. Crittenden, the chief financial officer, reviewed the transaction for about 20 minutes with the prince’s head of business affairs.

With Citigroup’s preferred stock trading at around 20 to 30 cents on the dollar, the bank held out the carrot that investors might be able to convert it at a premium to its current market price.

Soon thereafter, Citigroup received word that the prince would go along.

For the prince, whose net worth was most recently estimated by Forbes at $21 billion, the new government action is just his latest investment setback.

Early this year, his company, Kingdom Holdings, reported a $7.9 billion loss as some of his biggest portfolio investments, like the News Corporation, Time Warner and Songbird Estates, which manages the Canary Wharf office development in London, have plummeted.

He has suffered further indignity at home, where the share price of Kingdom has lost more than half its value since the company went public on the Saudi stock exchange in July 2007.

The Abu Dhabi authority, like all global investors, has also been hit by the world economic downturn, as well as lower oil prices — and it has tended to have a much larger position in equities, especially those in emerging markets, than other funds.

Brad W. Setser, an analyst at the Council of Foreign Relations, estimates that the Abu Dhabi fund lost more than 30 percent last year, bringing its size down to about $300 billion from a peak of $480 billion — a figure that is much lower than some of the larger public estimates and one that executives within the authority acknowledge is closer to the truth.