The official commemoration of Hurricane Katrina's fifth anniversaryhas its own media center.

It is a complex of meeting rooms in the downtown Marriott hotel on Canal Street, where visiting journalists can receive story tips, Mardi Gras beads, even discounted hotel rooms.

The center is a stark contrast to five years ago, when National Guard troops—once they finally arrived—pointed loaded guns at members of the media, maybe because we were some of the only people left in town by then.

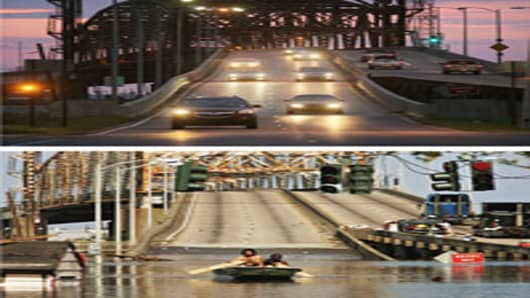

The anniversary is all about contrasts, as we found on our latest trip back to New Orleans this week. More than one resident has called it a tale of two cities and, as cliched as that phrase may be, it certainly applies here.

Unemployment is below the national average, but poverty is twice the national rate.

Aided by generous tax incentives, new businesses and entire industries are opening up in New Orleans. They include the Receivables Exchange, an electronic marketplace that allows businesses large and small to sell outstanding invoices to hedge funds rather than wait for payment. The exchange is booming, aided by a receptive business environment in post-Katrina New Orleans, said president and founder Nic Perkin.

Business is up 300 percent so far this year, said Perkin. "We're growing pretty close to as fast as we can."

And he believes it could not have happened, were it not for Katrina.

"Obviously, a human tragedy," added Perkin. But he believes it "permanently changed" Louisiana's business climate, by eliminating bureaucracies and spurring a plethora of tax credits.

But while new companies sprout here like wildflowers, many New Orleans area neighborhoods are overgrown with weeds, suspended in time—from August of 2005, to be exact.