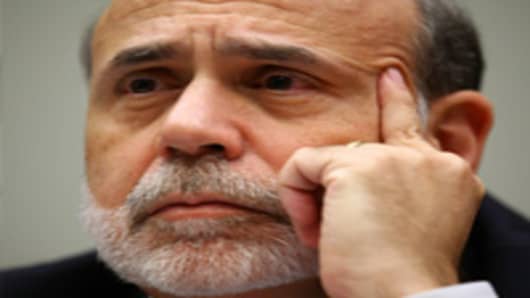

The announcement that the Federal Reserve is embarking on a renewed quantitative easing policy has prompted scolding from China, Russia and Germany. Which is perhaps the first thing I’ve heard in quite a while that makes me want to support Ben Bernanke.

Look, I understand the criticism of further easing—even if I think moralistic language about “debasing the currency” and an “unsustainable” monetary policy, or talk of “hyperinflation,” is usually evidence that the critics have doffed their economic analyst hats and started playing the role of grand inquisitors.

The most valid critique of quantitative easing is not that it will destroy the dollar. It’s that it probably will not work to improve the conditions of the domestic economy. We’re caught in a liquidity trap coupled with a post-boom economic reset. Releasing more dollars into the banking system will not spur more lending or economic growth as long as we’re still working out way out of the bad investments—which include financial positions keyed around mortgages, capital expenditures keyed around suburban sprawl, and worker skills built around the housing sector—from the boom.

There are lots of secondary effects of the likely failure of quantitative easing. First and foremost, it could undermine confidence in the Fed to manage the economy. But this strikes me as a feature disguised as a bug. If it leads, eventually, to a Fed less able or willing to intervene in the economy, we’ll all be better off in the long run.

The scolding from political leaders from around the nation, however, is not rooted in the potential ineffectiveness of the Fed’s policies. It is rooted in the opposite: a view that the Fed’s policies will successfully touch off inflation and dollar depreciation. This is what the German finance minister meant when he said that the Fed was manipulating the currency to “artificially lower the value of the dollar.”

What’s truly troublesome about the international complaints is that they turn on the planted axiom that the U.S. should be responsible for holding up its end of the bargain in some sort of implicit fixed-exchange rate deal. That is to say, the leaders of foreign countries seem to be demanding a return to Bretton Woods without any treaty or pact.

The only answer to this demand should be for Tim Geithner or Ben Bernanke to quietly and politely instruct the foreign critics to shut their gobs. The monetary policy of the United States should not be an arm of our foreign policy and certainly should not be run to satisfy the policy views of foreign governments. And when those governments have a history of their own currency manipulations and debt defaults—well, let’s just say that the critics don’t have clean hands here.

Let’s set this straight. There is no plausible evidence that the Fed is conducting its quantitative easing policy to manipulate exchange rates—if it were, it would be far easier to directly intervene in foreign exchange markets. The Fed seems genuinely convinced that it needs to undertake further easing to conquer consistent unemployment, ward off deflation, and stymie any chance the U.S. economy "double-dips" into a renewed recession. I might think Bernanke’s going about this all wrong, but I do not doubt his motivations.

Disturbingly, even some friends of sound money seem to be rejoicing in the drubbing of Ben Bernanke. So let’s get this straight, people. The only thing worse than fiat money open to the inflationary instincts of central bankers is an arrangement of fixed exchange rates by bureaucrats.

The instinct to fix exchange rates is perfectly normal. Under a gold standard, exchange rates were fixed against the price of gold. Once the world’s governments departed from the gold standard, we entered a world perpetually on the verge of economic chaos. Fluctuating currencies make international business planning far riskier and more complex. They perpetually undermine the economic policy goals of governments who cannot control what traders do with their money.

The hope behind fixed exchange rates is that we can restore the stability of the gold standard without gold. It’s a plan doomed to fail.

What the world has failed to grasp is that there is one thing much worse than fluctuating fiat moneys: and that is fiat money where governments try to fix the exchange rates. For, as in the case of any price control, governments will invariably fix their rates either above or below the free-market rate. Whichever route they take, government fixing will create undesirable consequences, will cause unnecessary monetary crises, and, in the long run, will end up in ignominious failure. One crucial point is that government fixing of exchange rates will inevitably set "Gresham's Law" to work: that is, the money artificially undervalued by the government (set at a price too low by the government) will tend to disappear from the market ("a shortage"), while money overvalued by government (price set too high) will tend to pour into circulation and constitute a "surplus."

We seem perpetually doomed to make one version or another of this error: the government intervenes in markets with wildly distorting results, and then we try to cure the “market failure” created by the intervention with further intervention. Bank deposit guarantees create more hazard, so we introduce reserve requirements. Reserve requirements crowd banks into trades favored by regulators so we wind up bailing out banks when it turns out the regulatory view of risk was wrong. Bailouts create moral hazard and scramble risk management, so we introduce compensation controls and so-called resolution authority.

The same with currencies. Viewing the chaos introducing by floating currencies pegged to nothing other than bureaucratic goals for various economies, many want another set of bureaucratic rules. It’s planning all the way down.

I’d like to express confidence that at some point the ideology of bureaucrats—that competent rule-making can replace market processes with something better—would crack under the pressure of such a long and grim history of failure. But I don’t have that confidence. If asked to bet on whether bureaucrats will wind up in the dustbin of history, or directing the trash collection for the ruins of once prosperous economies, I'd just decline to take a position because I find profiting from catastrophe unappetizing.

It is nice, however, to see that so far the competing domestic goals of policy makers seem to be producing gridlock on the road to international rules to “correct” so-called imbalances in trade. The word out of South Korea this morning is that policy makers agreed to someday agree about a policy to address trade imbalances, falling well short of the Obama administration's goals for bureaucratically arranged numerical goals for trade. So perhaps there is some room for hope, after all.

Perhaps Ben Bernanke deserves some credit for this. If quantitative easing helped undermine the authority of the U.S. to call for fixed trade balances, Bernanke deserves at least two cheers from enemies of central planning.

_____________________________________________________

Questions? Comments? Email us atNetNet@cnbc.com

Follow John on Twitter @ twitter.com/Carney

Follow NetNet on Twitter @ twitter.com/CNBCnetnet

Facebook us @ www.facebook.com/NetNetCNBC