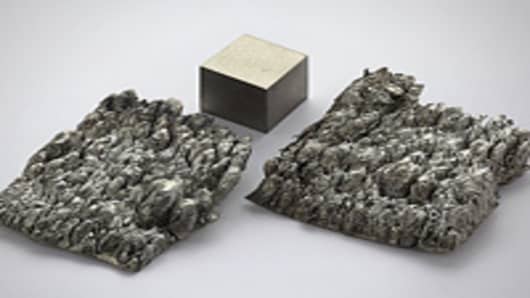

Rare earth metals are becoming dearer than gold. Yes, they sport tongue-twisting names like neodymium and samarium.

But these obscure metals, a market totally only $2.5 billion, are set to be 21st century stockmarket darlings.

Why? They’re essential guts in green technology—everything from electric car batteries to wind turbines to solar panels. They’re even embedded in cell phones and flat-screen TVs.

And the rare earth cache is getting squeezed. China supplies 97% of the world’s market and is cutting its exports more every year, leaving countries like Japan scrambling to stockpile the metals. The race is on to develop new mines outside China.

“We’re waking up the fact that new devices like smartphones and iPads require rare earth metals,” says Jim Puplava, chief executive officer of money management firm PFS in San Diego. “You’re looking at big demand, but only three major players.”

Only one of them—Molycorp Minerals—is based in the U.S. The other two are in Australia and Canada. They’re still getting up and running, but their stocks are soaring. Molycorp, for example, has doubled in price .

A slew of smaller players, mostly in Canada, are still exploring for the coveted metals.

Analysts gush at the prospects, though.

“We’re just on the cusp of what share prices can be,” says Kevin Kerr, president of Chicago-based Kerr Trading International, and who sees rare earth metals as the new oil. “It’s a bull market.”

That why these 17 metals—once ignored—are now coveted. Neodymium, the most prized metal of all, is used in high-strength magnets in motors and lanthanum in electric car batteries. A Toyota Prius alone uses 25 pounds of rare earth metals to power its hybrid engine.

“Demand is skyrocketing,” says Kerr. “And with a lot of these metals, there’s no replacement.”

Investors have missed the ground floor investment stage. But Kerr still sees significant upside in a “red hot market” by waiting for market corrections.

China holds the cards

China decided twenty years ago to dominate rare earth metals, says Puplava. The problem is that only a few companies are listed on the Hong Kong Exchange, making investing difficult.

“Investing in China is only for extreme risk takers,” says Jack Lifton, an independent consultant. “Getting your money in and out of China is the problem.”

But the power equation is starting to change. Since 2007, there’s interest in revving rare earth companies. Lifton adds that “all other rare earth mining was shut down by Chinese pricing.”

The U.S government is giving the niche a push. Recent legislation passed in the House called for more research into rare earth domestic production. The reason: the U.S. military is a big user of rare earth metals for weapons like smartbombs.

Cowboy capitalism ...?

Despite rapid movement, there’s no official price mechanism and investment options are limited. “It’s cowboy capitalism at its best,” says Lifton.

Kerr recommends investing in the top three players and a few junior producers. Holding the physical assets is next to impossible, he says, since the strategic ones are toxic.

Molycorp, once one of the world’s largest producer, is set to open shop again in 2012. “It already has the infrastructure to produce,” says Kerr. It’s set to mine about 20,000 tons of rare earth metals. It’s currently valued at over $3 billion, adds Lifton, more than the entire rare earth market.

Kerr also likes Lynas Corp., which trades in Australia under the ticker LYC, another major rare earth producer in Australia, and Great Western Minerals Group. It’s a Canadian company, trading in Toronto under GWG, that also owns rare earth mines in South Africa. “They’re all established, fully integrated and ready to go,” says Kerr.

Given the rapid rise in rare earth stocks, Kerr advises buying partial positions in these big three—set to dominate the Western market. Once the stocks drop 30% to 50%, he advises buying more shares.

Juniors are also appearing, Kerr adds. They include exploration companies like Avalon Rare Metals (AVL) and Stans Energy (RUU), both trading in Canada. “They have high quality deposits and infrastructure,” says Kerr. “As you move down the list, you move up the speculative scale.” (The CEO of Avalon recently appeared on CNBC).

Kerr also sees the juniors as possible takeover targets. “Many are under-funded,” he says. “And there will be more consolidation, since mining is so cost intensive.”

The Van Eck Rare Earth/Strategic Metals ETF launched in October, is another alternative. But only 32% of fund assets are invested in rare earth producers; the rest is in titanium and other metals. “The companies can be very volatile,” says Edward Lopez, a product manager at Van Eck. “Use it as a speculative growth opportunity.”

Jim Puplava agrees. “You’re investing in smaller players,” he says. “If you get a small correction, they get slaughtered.”