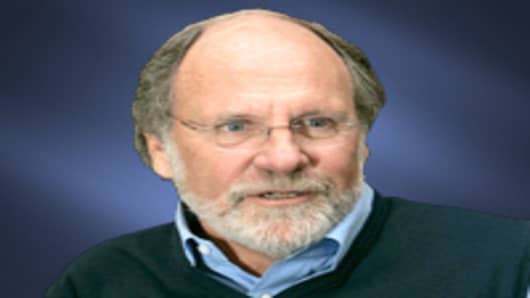

Jon Corzine may not be the wild risk taking trader that some media accounts portray, but the downfall of MF Global can be laid squarely upon his shoulders.

Corzine reshaped the trading operations of MF Global , hiring thousands of new employees while laying off long-termers. And he made the transformation in a short period of time. The model he was trying to impose, very clearly, was Goldman Sachs of the 1990 and early 2000s. And during that time traders often operated as if the firm was just a big hedge fund.

But Corzine’s weakness was not an undue appetite for risk. He wasn’t a guy who looked for the riskiest tranches of debt or got his thrill with long odds.

His weakness seems to be something more like overconfidence. In his head he holds something that is almost the opposite of the efficient capital market hypothesis. It’s what one former co-worker called the “efficient Corzine hypothesis.”

“At a very deep level, Jon believes that he can spot opportunities overlooked by markets—and make a fortune,” the person said.

In particular, Corzine believed—according to two sources familiar with the matter—that credit markets in Europe were suffering from “market dislocation.” Sovereign bonds backed by various rescue facilities were trading at levels that implied a swift default—even though it appeared that European regulators would act to prevent default.

Corzine hired a new trading chief at MF Global as he pushed for more proprietary positions. Meanwhile, Corzine himself pretty much personally oversaw the acquisition of European sovereign bonds, which he built up to a giant portfolio of over $6 billion.

One trader at the firm pointed out that this portfolio doesn’t contain much of the riskiest sovereign borrower in Europe—Greece. This, the trader said, demonstrates that the motivating urge behind the expansion wasn’t “risk appetite” but a belief that the market was over-pricing risk for safe sovereign bonds with short maturities backed by the European Financial Stability Facility.

Corzine didn’t have much in equity capital to deploy for this expansion. So it was built mostly by borrowing money in the short term market. At the end of September, MF Global had $1.23 billion in book equity—and $41.05 billion in assets.

At that level of leverage, even a small drop in the value of the assets can financially cripple a firm. What’s more, lenders understand that the firm is vulnerable to a drop in the value of assets and often begin to demand larger haircuts on the securities put up for loans—which quickly eats into existing equity capital. At some point, it becomes necessary to raise more equity or sell off assets—which can mean that the firm needs to realize even deeper losses.

Corzine thought that he was buying safe assets at discounted prices.

They were on sale, from his way of seeing things. This only became a problem because he borrowed so much money to buy the assets. The risk taking wasn’t so much what he bought—but the Lehman-like level at which MF Global funded the purchases. A non-leveraged firm buying the very same assets would have likely been able to survive.

Questions? Comments? Email us atNetNet@cnbc.com

Follow John on Twitter @ twitter.com/Carney

Follow NetNet on Twitter @ twitter.com/CNBCnetnet

Facebook us @ www.facebook.com/NetNetCNBC