There's some typical descriptors that restaurants might use to help sell a fish special: buttery, flaky, fresh. But there's one that you'd think might make it impossible: venomous.

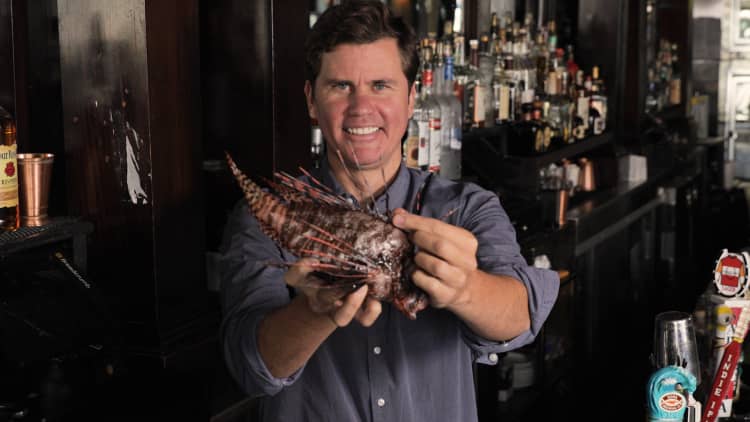

Yet somehow that hasn't stopped entrepreneur and restaurateur Ryan Chadwick, who is on a mission to bring lionfish, a venomous and invasive species wreaking havoc in the Atlantic ocean, to dinner plates across the country.

"The more you eat this fish, the better it is for the ecosystem," Chadwick tells CNBC Make It. Since lionfish were first released off the coast of Florida 30 years ago (most likely by aquarium owners), their numbers have swelled enough to harm reefs, native fish populations and ecosystems from Jamaica, to the Gulf, to the Bahamas.

It was in the Bahamas that Chadwick saw the impact firsthand, on one of his monthly diving trips to Hummingbird Cay in 2009. The fish he was used to seeing swim around the reef had dwindled and given way to lionfish, newcomers capable of eating 30 times their resting stomach volume, according to Lad Akins, Reef Environmental Education Foundation director of special projects.

"We know lionfish are gluttonous predators and they can do a lot of damage," he says. "When you affect one part of the ecosystem, it's felt throughout the entire system." For example, not only do other fish suffer (in some cases native fish populations dropped nearly 80 percent in just a few weeks), but algae is often left unchecked and can destroy coral reefs when herbivorous fish are depleted.

Efforts by locals and conservationists to eradicate lionfish proved painstaking. The species doesn't respond well to bait and usually lingers in hard to reach areas like deep reefs, meaning each fish has to be speared by hand. That's a dangerous proposition, since a stick from one of the fish's 18 venomous spines can inflict more pain than a jellyfish sting.

So they developed a unique solution: eat the lionfish. While in the Bahamas, Chadwick sampled what had increasingly become a common Caribbean meal, pan-fried lionfish. Once the venomous spines are cooked or removed, they become a non-issue, and it turns out lionfish are as tasty as any other white fish.

Chadwick had just opened a Caribbean-inspired restaurant, Norman's Cay, back in New York City, and saw an opportunity to add a dish with a cause to his menu and jumped on it.

"I wasn't really sure if it was going to work but it was something that I was willing to do to take that risk," he says.

There was just one problem.

"We couldn't source it from any fish retailers ... so I would go down to down to the Exumas with a big old Coleman cooler and shoot 30 or 40 fish, bring it back on a Monday [and] give it to our chef in the restaurant," Chadwick recalls. For about $26, diners had the option of pan-fried lionfish or a traditional lionfish "escoveitch," which is prepared with sautéed onions, peppers and carrots.

When customers responded positively to both the taste of the fish and its sustainability, Chadwick thought he was on to something. When other seafood restaurants began asking where he was sourcing his lionfish, he knew he was.

"I was like, 'If that happens for us, I wonder if we can get a few other restaurateurs hooked on this,' no pun intended," he recalls.

But having grown tired of carting lionfish in coolers through customs, Chadwick and his business partner, Charlie Gliwa, started recruiting local divers in Florida. What ensued was something of a weekend road show along the Panhandle.

"[We] spent time in each each port town and hung out with some divers to come out for beers and barbecue and ended up putting together a great team," Chadwick tells CNBC Make It. He paid a handful of divers about $5 for each fish they caught and launched his distribution company, Norman's Lionfish.

Instrumental to the success of somehow simultaneously building up both supply and demand for a venomous fish few customers had even heard of was the fact that Chadwick's own restaurants offered at least some stability in the beginning.

"If no one else wanted to buy this fish, I at least had someone to buy it which was myself," he explains.

Eventually the orders spread beyond just the seafood restaurants Chadwick operated in Aspen, Montauk and Nantucket. Chadwick and Gliwa even convinced a seafood trucking company to accept shipments of lionfish despite concerns about getting stuck by the fishes' spines and not meeting volume minimums. The move allowed Norman's to offer lionfish at a price that's in line with most popular seafood.

"They're willing to do this because of the mission — because of what we all want to do here," he says of the trucking company, adding that all seafood stands to benefit if controlling the lionfish scourge succeeds. Considering shipments have grown more than tenfold — from about 40 pounds per week when Norman's Lionfish launched a year and a half ago, to around 600 pounds per week today — Chadwick is hopeful he can continue to market lionfish as a mainstream option.

It's a hope that's shared even by conservationists like Adkins, who doesn't often find himself in the position of cheering for an increase in fishing rates. "This is a fish that we need to fish," he says, adding that he's seen improvement in ecosystems where people are hunting lionfish.

Chadwick closed Norman's Cay in 2017, but his current New York City restaurant, Grey Lady, serves the fish as a special. However, Chadwick's proudest bit of proof that lionfish is catching on is evident in his distribution company's largest customer: Whole Foods. The specialty grocer began offering the fish last year.

"My thinking was, if we can hit that massive grocery grocery store then we'll be able to kind of sell to the masses," Chadwick explains. "Like why would you not want to try it if they price it in the same line as a snapper, grouper, salmon?"

Considering that each fish has to be caught by hand, it might be surprising that lionfish retails for a reasonable price. Whole Foods initially offered lionfish in its stores at around $9.99 per pound, about the same as the store's farm-raised salmon.

"The fish should sell for $18 to $20, but again the idea is to sell more fish and get in more people's homes so they can try it," Chadwick explains.

And while the business is profitable and sold roughly $100,000 worth of lionfish in the past year, Chadwick is quick to clarify that making money is not what they set out to do with the company. The company regularly donates fish to sustainability events and chefs around the country.

"The mission is not make as much money as possible ... and don't ever own a restaurant if you want to do that either because that's not the idea," Chadwick says laughing. "It's more about a passion to do something you want to do ... and two years ago the idea was to start a lionfish distribution business from scratch and that's what we did."

Don't miss:

- How a 33-year-old turned $200 into $1 million in 92 days selling Kevlar pants online

- This 24-year-old made $345,000 in 2 months by beating Kickstarters to market

Video by CNBC's Richard Washington and Nate Skid.

Like this story? Like CNBC Make It on Facebook!

This story has been revised and updated.