The story, and the only story, is China. That can be summed up by looking at their outbound capital flows, which are hitting record levels.

China has been around for thousands of years but it is a teenager when it comes to capitalism and like any other teenager they don't yet have the judgment, experience or interest in asking for help. And it is a helluva a time for a case of first impression and on the job training.

The issue is not that China doesn't want to do the right thing – assume that they do. It is that they don't know how.

China doesn't want its currency to decline, a common mistake that everyone makes, including "China experts" because a declining currency leads to capital flows out of the country, since no one wants their buying power to be decimated — particularly in a declining economy. That's a double whammy.

And when capital flows leave, China's reserves take a hit. Even if the money stays in China but is converted into dollars (each individual is allowed to convert $50,000 per year out of the yuan, which is why we are seeing such a big hit to the yuan in December and for the new year, in January) it can no longer be counted as a reserve. This, of course, is evident in the massive selling of Treasurys by the Chinese, which has been more than offset by the safe haven trade of others.

But make no mistake: Treasurys are at risk as other reserve nations sell as well to shore up their own economies. Saudi Arabia is a notable example.

The solution, which won't be easy, has to be a coordinated effort to prop up the currency. That means the Chinese have to ask for help from the U.S. Federal Reserve and other central banks. Right now, they continue to act like an emerging-market economy – trying to keep rates high (still benchmarked at 4.35 percent plus deflation of 6.5 percent gets you to real rates of 11 percent).

Emerging economies do this to keep capital from flowing out with the thought that at least the buying power of their currency will be preserved or even appreciate. However, the size of China's economy dictates developed market treatment, where it is more important to maintain credibility in the currency rather than focus on interest rates alone.

The other question is: What is causing the massive outflows? Are circumstances actually much worse than the allegedly flawed data that China releases would indicate? Likely, yes.

So, it's a mess and won't improve. It can't improve unless there is a coordinated effort to shore up the currency and unless China asks the Fed for help in figuring out their mess. By the way, the U.S. participates in coordinated efforts all the time — it's what central banks do.

Adding to the issues facing China is that they have done a massive job of increasing their debt and recently have been lowering credit standards. At one point recently, the even allowed homes to be used as collateral in retail investor margin accounts. But with rates remaining so high, the defaults will continue to pile up.

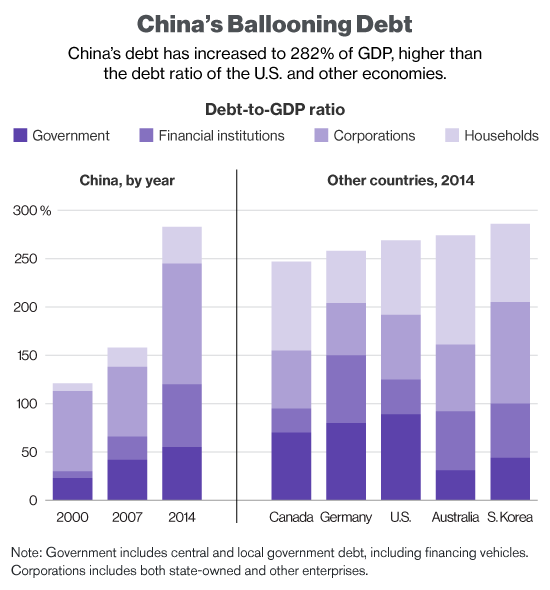

Put in proper perspective, China's state and local governments are on the hook for more than $4 trillion in funds — bigger than Germany's entire economy — that was borrowed for infrastructure, real estate, etc. In fact, China's debt buildup has been twice the size of the U.S. build leading up to 2008 and is almost three times their GDP. That's much larger than any other developed economy that actually has experience as capitalists.

Here is a chart from McKinsey:

So, with China continuing to atrophy and still piling on debt, the currency will decline — despite China's best intentions to support it. Then, oil will trade lower (inverse relationship to the U.S. dollar, leading to lower demand) and the U.S. markets may test the low end of the trading range, even though I believe that the true impact to the U.S. economy is de minimis; it's more a sentiment, global markets trade than a fundamental issue with domestic and European mid-market economic growth.

This sets up for a compelling buying opportunity at some point — and we see value.

Compounding the issue may be that U.S. profit margins have peaked as labor costs rise, making the upcoming earnings season very interesting. Still, I remain optimistic about both markets and the economy, focusing on the U.S. and Europe. The peaking of margins in the U.S. doesn't bother me as much as others because the reason is that employment and wage growth are the primary culprits, offset somewhat by declining input costs such as commodity deflation.

Corrections are a normal course for markets. The best that can come out of this right now is that I can think of a number of former traders I used to work with who would welcome a 29-minute workday! That's exactly what happened Thursday in China after circuit breakers kicked in and shut down the exchanges. In fact, some of the people I used to work with would excel under such circumstances – I have witnessed much greater capital loss than 7 percent in less time!

Commentary by Stephen Weiss, the chief investment officer and managing partner at Short Hills Capital Partners. A former tax attorney, Weiss has been in the investment industry for 28 years, virtually all of this time involved with hedge funds. He has held senior management positions at Salomon Brothers, SAC Capital, and Lehman Brothers. Additionally, Steve was co-founder and CIO of MSW Asset Management, a long/short equity fund. He is also the author of three books, including his latest, a novel titled: "Unhedged: A Killing in the Market." Follow him on Twitter@stephenLweiss.

For the latest commentary on markets in U.S. and around the world, follow @CNBCopinion on Twitter.