President Obama has announced a new plan to levy a tax of $10 on every barrel of oil, to be paid by the oil companies.

The plan has plenty of problems, not least its viability. Even the president doesn't seem to know what he wants.

For example, is the tax expected to fall on production or consumption?

Ed Crooks, the energy editor of The Financial Times, said in a tweet that the amount mentioned, a tax of $32 billion per year, would be consistent with a production tax. Given that oil companies are losing money hand over fist at current prices, reducing net revenues by $10 per barrel would have the effect of destroying the domestic oil business.

Tweet

I can believe the White House is bad at math; I doubt they would conceive of a tax directly intended to undermine U.S. energy independence and gut a business already facing a historic recession. That would be insanity itself.

More likely, the president means a tax on every barrel oil companies sell to consumers, which implies a tax the equivalent of 25 cents on every gallon of gasoline, heating oil and pound of plastics produced. So, rather than the obfuscation, let's just call it a gasoline and petroleum products tax.

Is this a good idea?

First, let's discuss what it wouldn't do. A consumption tax would not materially influence the price of either WTI or Brent crude, or the differential between them. Oil consumption can prove quite sticky.

For example, despite the precipitous drop in oil prices in the new year, U.S. gasoline consumption appears to actually be down a bit. Consequently, were prices to increase by $10 per barrel — essentially back to early December levels — we would expect no measurable impact on U.S. oil consumption. Whether oil is just cheap or laughably cheap doesn't matter too much to the consumer.

In fact, our analysis suggests that an oil price up to $75 per barrel would have no material effect on either US mobility or the country's economy. The consumer is indifferent to oil at $30 per barrel without a tax or $40 per barrel with one. Thus, at current oil prices, a $10 per gallon tax hike would be nothing more than an effective sales tax hike, and a regressive one at that.

On the other hand, at high oil prices, an oil tax can make a material impact. If WTI stood at $115 per barrel, adding a $10 per barrel tax could be enough to push the economy into recession or, at a minimum, would certainly exacerbate any "secular stagnation." Put another way, the impact of an oil tax depends greatly on the prevailing price of oil at the time.

Today, a $10 tax would not influence oil consumption and would act as a simple tax increase to be borne disproportionately by lower to middle income consumers.

Taxes can beneficial, if they are spent the right way.

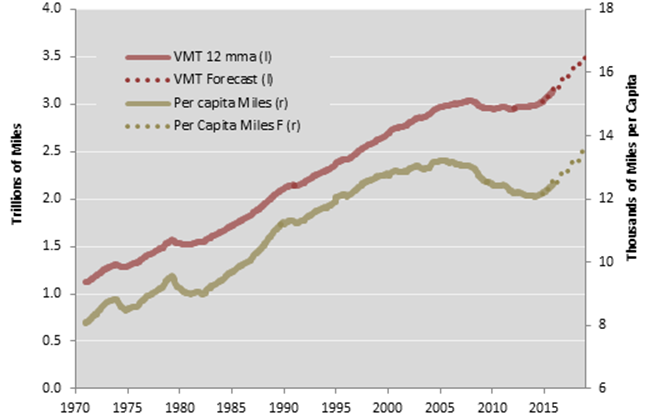

U.S. vehicle miles traveled (VMT) are rising rapidly, and if my hometown of Princeton is anything to go by, traffic is going to get a lot worse. Our forecast calls for U.S. vehicle miles traveled to recover to pre-recession levels by the end of 2018.

We will need new roads even as we maintain our incumbent road system, and we have to pay for that. A gasoline tax is a good solution.

US Total and Per Capita Vehicle Miles Traveled Source: US Department of Transportation

But no one likes the idea.

As a result, the government has tried to finesse the issue of highway funding by clutching at a grab bag of revenue sources, including selling oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Nevertheless, much as all of us would prefer to avoid a tax increase, directly linking road maintenance to gasoline consumption is the structurally sound approach.

Were it so simple.

To begin with, not all gasoline taxes are used for roads; a portion goes to mass transportation. We also pay plenty in tolls that have nothing to do with roads.

For example, crossing the George Washington Bridge to New York costs $15. Twenty miles upstream at the Tappan Zee Bridge, crossing the Hudson costs two-thirds less. The reason: The operator of the George Washington Bridge, the Port Authority of NY/NJ, uses tolls to subsidize all sorts of things, including a hefty contribution to the Freedom Tower.

Unfortunately, the comingling of user fees with unrelated subsidies leads to cynicism. The punishing toll at the George Washington Bridge has nothing to do with maintaining the structure; a large portion goes to insure Condé Nast has nice offices at the World Trade Center. Robbing the poor to give to the rich is no way to create enthusiasm for increased fuel taxes.

The president proposes to spend oil taxes on "clean" transportation infrastructure for high speed trains, mass transit and self-driving cars.

Now, here's the thing. We already have high speed rail. Indeed, we've had it for half a century.

Visit the Princeton Junction train station, and you will see a plaque which says that Amtrak's Metroliner was successfully tested on the Northeast Corridor track at 170 miles per hour — in 1969! Why then does it still take an hour to travel the 60 miles to New York? Because of speed limits on the tracks. We have high speed rail. We just don't have a ready place to use it, at least in the congested Northeast Corridor where train travel makes the most sense.

And then there's the price of tickets. Take Amtrak round trip from New York to Washington today, and you might pay $300. Take Bolt Bus, and you'll pay $60.

In what sense is Amtrak "public transportation," when it costs literally five times as much as a ticket on a private bus and three times as much as driving? How exactly is that in the public's interest? And is high speed rail going to be cheaper than Amtrak or Metro North? I doubt it.

"We don't need 21st century transportation. If we could return to the traffic congestion levels of 1970, that would be good enough."

Unfortunately, the president is suggesting that the government will suddenly develop competence where history shows it performs poorly.

Moreover, the president's plan ignores chronic, well-known problems which could be solved in some cases with much less money.

As an East Coast resident, I can tell you that the president would have gotten a lot more traction if he'd promised to speed up the tolls on the GW Bridge and double the capacity of I-95 north of New York. We don't need 21st century transportation. If we could return to the traffic congestion levels of 1970, that would be good enough.

Commentary by Steven Kopits, president and managing director of Princeton Energy Advisors, an oil and gas consulting firm that advises hedge funds and oil equities investors. He previously ran the New York office of Douglas Westwood, energy industry consultants, and earlier worked as an investment banker with Dahlman Rose & Co.

For the latest commentary on markets in the U.S. and around the world, follow @CNBCopinion on Twitter.