When the public sits up and notices the art market, it is usually when an anonymous buyer pays a mind-boggling sum to acquire a prized painting or sculpture.

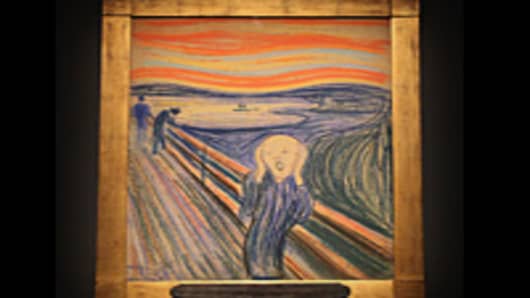

In 2012, Edvard Munch's "The Scream" fetched a record $120 million, a Mark Rothko abstract soared to $87 million and a Renaissance drawing by Raphael sold for $48 million - all in a year when making ends meet was most people's priority.

Yet Steven Murphy, the first American to head the auctioneer Christie's since its creation in 1766, is convinced the key to future success after another bumper year of sales lies not with the "one percent", but a much broader pool of art lovers.

The 58-year-old, who worked in publishing and music before his surprise appointment to the head of the world's largest auction house two years ago, wants to rid the art world of its stuffy image as a club exclusively for the rich.

"It's sexy and it's cool and it's news to talk about the most important work in a single sale on a single evening, but one has to be careful of the myopia as a business of focusing only on that very important activity," Murphy told Reuters.

"Twenty percent of our buyers this past year were brand new to Christie's, never bought here before," he said in an interview at the company's headquarters in central London, sitting beneath a small Picasso being sold next month.

He was referring to one of the encouraging statistics in the company's annual sales report, which on Thursday showed record revenues of 3.9 billion pounds ($6.3 billion) in 2012, a rise of 10 percent on 2011.

In 2009, when the art market contracted sharply due to the global financial crisis, sales were just 2.1 billion pounds.

Asia Down but Not Out

The overall increase in 2012 came despite a slump in Christie's auction sales of Asian art, which fell by a quarter to 415 million pounds after providing the engine for growth in recent years.

Competition from Chinese auctioneers and the end to a speculative bubble in some Asian art contributed to the decline, but Murphy said the region had the potential to grow again longer term.

"I think the opportunity in Asia is far bigger than any of us in the art business have truly tapped into," he said.

In contrast, Christie's saw private sales surge 26 percent to 631 million pounds, and Murphy expected deals behind closed doors to be key in maintaining growth in 2013 and beyond.

"Look for a big increase in our private sales activity," he said. "Our current clients want to do more of that."

Murphy, whose laid-back manner stands out in the London art scene, said he was convinced more private sales did not mean less business in the auction room, still the mainstay of Christie's income.

A key part of Murphy's strategy since arriving has been to build its online presence, both by attracting visitors to the website and encouraging them to bid over the internet.

From six online-only auctions in 2012, the company will hold more than 30 in 2013, and while digital sales tend to be for more modestly priced items, Edward Hopper's "October on Cape Cod" sold for $9.6 million to an internet bidder in November.

Explosion in Interest in Art

"One of the things that is driving the opportunity for a company like Christie's is cultural," he said.

"There is a huge cultural surge around the world toward the experience of art. Museum attendance is way up on the previous year and the year before that...People are accessing art on their iPads, on their laptops, on their iPhones."

By expanding its online presence, Christie's aims to capture more business in the mid- to lower-tier markets, away from the multi-million-dollar deals that grab the headlines.

Murphy pointed to a 20 percent rise in sales at Christie's South Kensington offices, which specialise in lower-end art and antiques.

For Christie's, that sector is key in terms of the bottom line because profits from it outstrip those from more high-profile post-war, contemporary, impressionist and old master art, Murphy said.

He believes that only a "tiny percentage" of clients are buying art purely as a "commodity", or alternative investment at a time when stocks and bonds have delivered modest returns while some artists' values soar.

"From the top end, no-one has bought a Rothko for more than $30 million who doesn't want the Rothko and at the middle and lower end the purchaser of the 20,000-pound Jasper Johns lithograph ... really wants that work," he argued.

"What is happening is that people of wealth are choosing not to invest in other areas, and therefore they have more available for the activity they already love, so it's not money management as much as personal choice."

And if equities start to pick up again?

"I am here to say that when the markets go up there is more money to spend so actually our sales go up, so we don't want to see the stock market do anything but go up."

Christie's, a private company owned by French billionaire Francois Pinault, does not report profit or loss, only sales.

Its main rival is Sotheby's, slightly smaller in terms of sales. Sotheby's, listed in New York, posted auction sales of $4.4 billion last year versus $5.3 billion at Christie's.

Murphy confirmed the company was in the black. When asked whether it was more profitable now than when he joined in late 2010, he replied: "I can say that we're very happy. There's wind in our sails."