When Jason Payne set out to find his girlfriend the perfect engagement ring, he was already facing more pressure than most men looking to take the plunge.

His girlfriend had ethical concerns and didn't want to risk sporting a "blood diamond," one mined in a conflict-riddled region of Africa where the sale of the stone helps fuel violence.

So instead, Payne proposed with a sapphire ring and felt good about his decision.

Then he read about something that promised to turn the diamond industry upside down — laboratories were successfully growing diamonds at equivalent quality to mined diamonds without the stigma, and they were being sold at a fraction of the price.

When his then-fiance, Lindsay Reinsmith, expressed an interest in adding the gemstones to the ring he picked out, the couple realized a gap in the market when they struggled to find anyone willing to work with them.

"People that actually grew laboratory-grown diamonds were not interested in selling them loose to a consumer," and none of the custom jewelers in San Francisco, where the couple lived, would work with laboratory grown diamonds, Payne tells CNBC Make It.

"So we founded Ada Diamonds to fix that problem — to create the company that we wish existed when we were going through our own personal journey to build a custom ring."

With less than $1 million raised from friends and family, the couple launched Ada Diamonds in 2015 to join the new, blossoming lab-grown diamond industry. Already in the industry was the likes of Diamond Foundry, backed by Leonardo DiCaprio (who starred in the 2006 film "Blood Diamond," which brought attention to the darker side of the diamond mining industry).

Sourcing lab-grown diamonds from growers around the world — from Tel Aviv to San Francisco — Ada Diamonds works to create custom engagement rings, necklaces and other jewelry pieces for clients. Everything is crafted by hand in the U.S. and generally comes in at about a 30 percent discount to mined diamond equivalents, the company says.

While lab-grown diamonds have recently gained in popularity — even the industry pioneers at DeBeers has announced it will sell them — the technology behind growing the gems has existed since 1953 when it was developed by General Electric. Then, the process was mostly used to produce cutting and polishing tools. As the technology improved, costs decreased and the idea of using diamonds grown in labs specifically for use in jewelry started steadily gaining traction over the last five years.

Rather than waiting millions of years for the pressure of the earth to crystalize carbon into a diamond, the laboratories from which Ada Diamonds sources its gems can simulate the same intense pressure and temperatures with heat and hydraulic presses and have a finished 1-carat stone in as little as a week.

"If you took the entire Eiffel Tower and you flipped it upside down and you put the point of the Eiffel Tower on top of that carbon, that's the pressure it takes to make a diamond," Payne explains. "They are the exact same crystal of carbon."

Generally, the growing process is negligibly cheaper than mining the gems, according to Morgan Stanley estimates. But in order to entice customers, lab-grown diamonds are typically priced at about a 30 percent discount to an equivalent mined diamond with similar specifications at the retail level.

But Reinsmith credits more than just a cheaper price for the growing popularity of lab-grown diamonds. Part of the reason she says Ada Diamond's sales have doubled for the past two years is because of changing consumer habits.

"These are the same consumers that demanded organic food … they care where everything comes from," she says. "On top of that they are really early adopters of technology and they appreciate sustainability."

What is, perhaps, most impressive is the quality of the gems themselves. Independent gemological societies like International Gemological Institute rate lab-grown diamonds much the same they would a mined diamond. Reports look mostly identical — with ratings for a diamond's clarity, color, carat size and cut — but include an indication if a diamond is lab-grown.

"It's something that a layperson cannot differentiate or distinguish nor could a gemologist with standard gemologist tools," Payne says, admitting that laboratories can use specialized lighting equipment and microscopes "to detect that the crystal structure is too perfect to have come out of the chaos of the earth."

How lab-grown diamonds actually compare

CNBC Make It took a $4,000 ring Ada Diamonds provided, featuring 18-karat white gold and a .95-carat lab-grown stone, to New York's famed diamond district. The same ring with a mined diamond would typically cost just over $5,000, according to diamond-pricing company Rapaport.

Without being provided context that the diamond was in fact lab-grown, one jeweler offered $3,800 and another $3,000 after inspecting it under magnification. While most jewelers matched the independent ratings for the diamond's clarity and color, not a single one was able to identify it as lab-grown. Once that fact was revealed, every offer to buy the ring was immediately revoked.

"So why did you have to bulls--- me?" one jeweler asks. Ironically, before we revealed it was a lab-grown stone, the jeweler jockeying to buy the ring for $3,800 even offered to replace the center stone in the ring we put in front of him with "a lab-grown diamond."

Dennis Dalton, a New York jeweler who says he's sold millions of dollars worth of diamonds over his 40-plus years in the industry, hasn't encountered any customers asking for lab-grown engagement rings. Offering both mined diamonds and lab-grown diamonds might raise suspicions in customers' minds as to which they are actually getting, he says. For that reason, Dalton has no plans to ever offer anything like the ring we brought in.

"The question is, it's a lab-grown diamond for $4,000. Why not use moissanite or cubic zirconia?" he asks, comparing lab-grown diamonds to lesser-quality synthetic gems that have been used as diamond substitutes. "If you're only getting [a] 20, 30 percent price difference, just pick the right [mined] diamond."

But in order to truly understand if it's worth buying a lab-grown diamond, it's helpful to first appreciate what spawned the tradition of buying diamond engagement rings in the first place.

Are lab-grown diamonds worth buying?

As investigative journalist Jay Epstein revealed in a 1982 story, the practice in America began in the 1930s after De Beers, then a monopolistic diamond company, launched a marketing campaign to stir up demand after discovering a supply-shattering cache of unmined diamonds in South Africa. Though there was a tradition of giving diamond rings going back centuries with European royalty, according to a De Beers spokesperson, in the U.S. at the time, a diamond ring was not a necessity, nor was it widely considered to be part of the engagement process. Yet after years of messaging to Americans, including the famous slogan "A Diamond is Forever," that all changed, wrote Epstein.

By 1979, De Beers wholesale diamond sales had increased to $2.1 billion (compared to just $23 million in 1939), thanks in large part to engagement ring sales, Epstein reported. A 1951 memo from N. W. Ayer, the marketing agency behind the campaign, explained, "for a number of years we have found evidence that the diamond engagement ring tradition is consistently growing stronger. Jewelers now tell us 'a girl is not engaged unless she has a diamond engagement ring.'"

But it wasn't just the idea of buying a diamond as a symbol of everlasting love that De Beers was selling. Eventually it began to tell the public exactly how to buy a diamond. In the 1980s, a new series of ads established a benchmark that people still believe today as the acceptable amount a man should spend on a ring by asking, "Isn't two months' salary a small price to pay for something that lasts forever?" According to a De Beers spokesperson, the amount was based on consumer research at the time.

The company also succeeded in propagating exactly what elements determined a diamond's worth. For a long time, a large emphasis had been placed on a diamond's size, until De Beers had a reason to change the notion that bigger was always better.

When the company's stranglehold on supply was threatened by a 1950s discovery by the Soviets of smaller diamonds in Siberia, De Beers partnered with its competition to avoid competing on price and promised to help market them. Ads explaining "how to buy a diamond" stressed the "importance of quality, color and cut," Epstein wrote, and drowned out a previous emphasis on carat size. According to a De Beers spokesperson, the practice of discerning how perfect a gemstone is by looking at its internal clarity was in place before the introduction of the the "four C's" (cut, clarity, color and carat size), as they are known, but the structure offered a more precise way of assessing value. The average size of diamonds sold fell from one carat in 1939 to about .28 of a carat in 1976, nearly mirroring the exact carat weight of the Siberian diamonds De Beers had been distributing, according to Epstein. In the diamond trade, the four C's remain the key characteristics people use to determine a diamond's worth.

In many ways, jeweler Dalton explains, those characteristics are now used by the diamond industry to unnecessarily squeeze more money out of unknowing consumers. For example, the difference between the highest clarity rating and the second highest is technically measurable, yet not visible to the naked eye.

"What they're not saying is it's outside the human vision range. Then the question is why are we measuring the invisible? To raise the price," he says. "It is in reality a ripoff by the industry not by [individual jewelers.]"

Instead, Dalton advises buyers work with a trusted jeweler to find the best fit for their budget. For example, even a lower-rated diamond with minor imperfections can look the same as a higher-rated diamond in a finished ring if the imperfection can be covered by a ring's setting. Doing so, Dalton says, could save thousands of dollars instead of unnecessarily jumping to a higher clarity rating.

And the idea of "unseen differences" very much sits at the heart of the debate between lab-grown and mined diamonds. To the naked eye, or even a jeweler's eye with a magnifying glass, they are exactly the same. They are both diamonds. But the simple fact that a diamond is a diamond wasn't the reason behind why generations of Americans bought into buying them. It has always been much more than that. More important than the diamond itself, N. W. Ayer noted, was the idea behind the diamond. The one constant message that appeared on every De Beers ad since 1948? "A diamond is forever."

"The only reason diamonds are the kind of money that they are, are historic reasons," Dalton says. "So when you grow them in a lab, the mystique is out of it because the natural stone goes back to the beginning of the earth. I mean there's a permanence, there's a meaning to that."

For now, lab-grown diamonds make up just 1 percent of annual diamond sales around the world, according to Morgan Stanley, but that share is expected to rise. Though it came as shock to many industry stalwarts that De Beers will begin to sell lab-grown diamonds through one of its portfolio brands, it's perhaps a sign the tide is turning. At least a little.

"They're not to celebrate life's greatest moments, but they're for fun and fashion," De Beers Chief Executive Officer Bruce Cleaver told Reuters in a telephone interview.

Whether or not people shopping for diamonds agree will hinge on exactly how a new generation of lovers chooses to symbolize just what "forever" truly means.

— Video by Zack Guzman and Richard Washington

Like this story? Like CNBC Make It on Facebook!

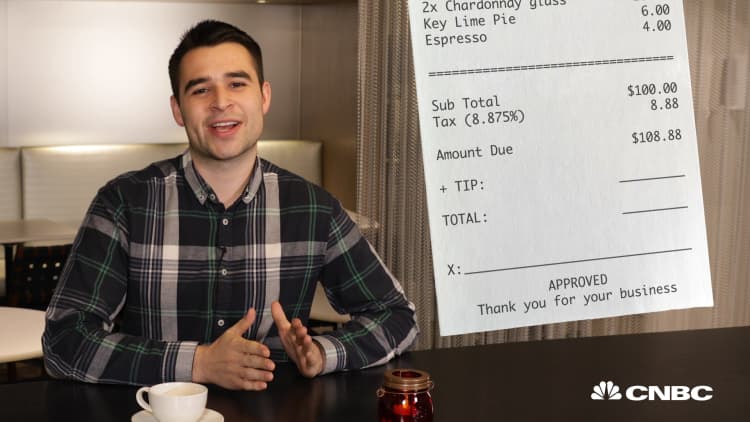

Don't miss: This simple tipping trick could save you over $400 a year