When Roberto and Carol Fernandez brought their son, Alex, into the world, they never anticipated they'd also become experts in special needs planning and autism advocacy.

Alex, 23, has spent the last two years at Triform Camphill Community in Hudson, New York, a 500-acre farm and residential community for young adults with special needs.

There, he helps care for animals and nurtures friendships with other residents.

"He's a hard worker. He volunteers for things and he takes care of people," said Carol, 63, and a retired attorney who specialized in working with children. "I'm very proud of the young adult that he's become."

Alex's full life at Triform comes at a high price: The Fernandezes estimated it would take $3 million to ensure he receives proper care for the rest of his life.

That meant Roberto and Carol, who reside in Newton, Massachusetts, needed to sketch out a financial plan that will last for the next 60 years — and that won't saddle Alex's sisters Sarah, 38, and Julia, 25, with the cost of caring for him.

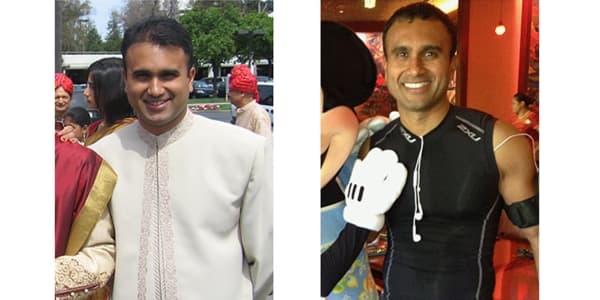

"That's a college tuition payment every year for the rest of his life," said Roberto, 61, and a professor of organization studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Sloan School of Management.

That's a college tuition payment every year for the rest of his life.Roberto Fernandezfather of Alex

"That led to the next step, which is to think about, 'what would be the way to do that?'" he said.

A crucial diagnosis

As an infant and toddler, Alex hit many of his physical development milestones right on time.

Then one day, when he was around 18 months old, Alex stopped responding to his name.

"I think for us it was the fact that he had a smattering of words and then he didn't say them anymore," said Carol. "He stopped talking."

Back in 1994, autism — a developmental disability that affects communication and social skills — wasn't in the public eye to the extent that it is today.

Doctors didn't immediately conclude that this was the condition affecting Alex, but after months of research, the Fernandez family took their son to an autism specialist for testing.

They received the diagnosis when he was 4 years old.

Today, as the medical community has honed its screening abilities, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that up to 1 in 68 children have been identified with autism spectrum disorder.

Fighting for their son

With a firm diagnosis of autism, Carol was able to seek the appropriate services, including speech and behavioral therapy for Alex.

"At the time, the services for developmental disorders weren't covered by insurance, so that was an out-of-pocket expense we had to go through," said Carol, noting her son had as much as 20 hours a week of therapy at a cost of up to $50 an hour.

Alex began attending public school when he was close to 5, receiving services through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

By then, the family had a sense of how much it would cost to care for Alex. They started stashing away at least $1,000 a month to prepare.

Then, they considered an even more frightening prospect. "What happens when we're gone?" asked Roberto.

Building trusts

Putting her legal know-how to work, Carol began researching special needs trusts.

This trust holds and manages assets for a beneficiary so that he or she may continue to receive Supplemental Security Income, Medicaid and other government benefits.

Once the Fernandezes realized it would take approximately $3 million to pay for Alex's care, they got in touch with Ralph J. Rotman, a financial advisor with the Atlantic Benefit Group in Boston, and their estate planning attorney.

The couple discovered they don't need to have the millions of dollars in hand right now to fund the trust; they needed to have the money when they die.

Because he's still working and generating income, Roberto has a $1 million insurance policy on his life. The couple also has a "second to die" policy valued at $2 million, which pays out upon the death of the second spouse.

These policies are known as whole life insurance, a policy in which a portion of the premiums the Fernandezes pay will accumulate in a cash value account.

This is different from term life insurance, which offers coverage for a limited period of time, say 20 or 30 years.

Once Roberto and Carol pass away, the death benefits will pay into the special needs trust, which is overseen by a trustee — and not pay out directly to Alex himself. This preserves any government benefits he receives.

"I'm very relieved to report that, yes, we have a plan in place that will not create havoc financially for his sisters," said Roberto.

Beyond life insurance

The special needs trust and the life insurance policies are just two pieces of the funding puzzle for the Fernandez family.

"A big part of our financial planning was knowing what government benefits you're entitled to," said Carol. For instance, Alex started collecting Supplemental Security Income at age 18.

Carol also discovered that though states offer benefits to help individuals with developmental disabilities, those programs and the degree to which they are funded will vary from one jurisdiction to the next.

Finally, the family had to ensure they have no constraints on their cash flow: They own their home and cars outright, and they pay off their credit card bills every month.

"We tried to make sure that whatever is happening — whatever the future brings — it's going to be made more secure if we can put away some assets," said Roberto.

Video by: Sophie Bearman, Qin Chen, Kyle Walsh