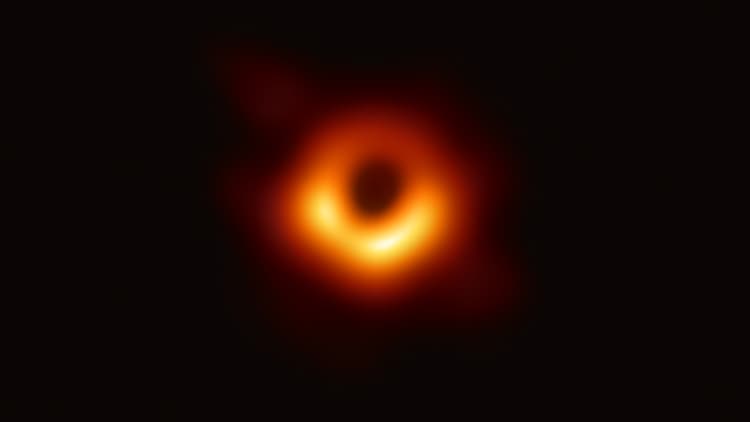

On Wednesday, after 10 years of planning and scientific investments totaling over $50 million, researchers released the first-ever image of a black hole. The image is a feat of modern science — experts say it's the equivalent of taking a photo of an orange on the moon with a smartphone — and international collaboration. Over 200 scientists across the globe contributed to the project.

One of those scientists is Katie Bouman, a 29-year-old computer scientist who began working on the project when she was a graduate student at the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) at MIT.

Bouman earned her bachelor's in electrical engineering from the University of Michigan and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Soon, she'll begin working as an assistant professor in the Computing and Mathematical Sciences Department at the California Institute of Technology.

But when she became involved in the project almost six years ago, she had no experience studying black holes.

"I go after problems that excite me. When I started this project, I didn't know anything about black holes and honestly, it was a risky project," Bouman tells CNBC Make It. "But my heart was in this project. I love this project, and I think that that's what makes it a success. When you get really smart people together, who are super motivated by the problem that they're working on, I think people will figure out the answers."

Bouman has gained recognition on social media from a number of public figures including Senator Kamala Harris, who wrote on Twitter, "Katie Bouman proved women in STEM don't just make the impossible, possible, but make history while doing it."

"So incredibly excited for Dr. Katie Bouman and her work to get the first picture of a black hole that was captured by the Event Horizon Telescope and rendered by HER algorithm," tweeted Reshma Saujani, founder and CEO of Girls Who Code.

But Bouman was just one of many scientists working on the project. Of the more than 200 researchers working on the project, roughly 40 were women, according to The New York Times. "There were lots of people on these teams," says Bouman. "I don't want to call out any person as the leader."

Nonetheless, Bouman's research led to the creation of a new algorithm that allowed scientists to bring the black hole image to life, a task with a level of difficulty that cannot be overstated.

"The black hole is really, really far away from us. The one we showed a picture of is 55 million light years away. That means that image is what the black hole was like 55 million years ago," explains Bouman. "The law of diffraction tells us that given the wavelength that we need in order to see that event horizon, which is about one millimeter, and the resolution we need to see a ring of that size, we would need to build an earth-sized telescope."

That is where computer scientists like Bouman came in.

"Obviously, we can't build an earth-sized telescope. So instead, what we did is we built a computational earth-sized telescope," she says. "We took telescopes that were already built around the world and were able to observe at the wavelength we needed, and we connected them together into a network that would work together."

That computational telescope is the Event Horizon Telescope, a constellation of telescopes in the South Pole, Chile, Spain, Mexico and the United States.

After researchers coordinated the super-powerful telescopes, scientists like Bouman were tasked with interpreting a massive amount of data.

"The team collected about five petabytes of data, and one petabyte is a thousand terabytes," explains Bouman. "Your typical computer has maybe one terabyte or so. So that would be like 5,000 typical laptops of data. It's just a huge. I mean, we basically had to freeze light onto these hard drives."

The data was so large that researchers had to transport the data by plane from around the world.

According to MIT, Bouman led one of four teams responsible for turning this mind-numbing amount of data into one verifiable image. If their team was going to claim to have produced the world's first-ever image of a black hole, they needed to be certain.

"We spent years developing methods, many different types of methods — I don't think any one method should be highlighted — because most of all, we were afraid of shared human bias," says Bouman. "If I made an image with my method and and it looks like a ring, I don't want someone to look at my picture and then subconsciously make their image look like a ring too."

For this reason, the computer scientists broke into four teams and did not communicate while they were analyzing the data. After months of the teams working independently, they all converged in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and ran their algorithms in the same room, at the same time.

The resulting image is one we now recognize as a black hole: a bright ring that's slightly brighter on the bottom.

The researchers spent the next several months trying to find flaws in their approach. When they were unable to "break" the image, they knew they had made a discovery.

This scientific necessity to eliminate bias and approach problems from several points of view is one reason experts stress that the sciences need a wide-range of diverse young people to enter the field, and Bouman agrees. She says she wishes that young people, especially girls and women, understood that pursuing a career in a field like computer science can lead to opportunities beyond sitting in front of a screen.

"If you study things like computer science and electrical engineering, it's not just building circuits in your lab," she says. "You can go out to a telescope at 15,000 feet above sea level, and you can use those skills to do something that no one's ever done before."

Like this story? Subscribe to CNBC Make It on YouTube!

Don't miss: