This week, the nation's eyes will turn to Tulsa, Oklahoma as the city commemorates the 100th anniversary of one of its most tragic and shameful events, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. In attendance will be President Joe Biden, as well as politician Stacey Abrams and musician John Legend.

A century ago, thousands of Black Tulsa residents had built a self-sustaining community that supported hundreds of Black-owned businesses. It was known as "Black Wall Street." This summer marks the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, a tragic event perpetrated on Black Wall Street that has been described as "the single worst incident of racial violence in American history."

The incident, which is estimated to have claimed the lives of as many as 300 people (the vast majority being Black), devastated a neighborhood that had grown over the previous 15 years to become one of the wealthiest enclaves for Black Americans in the country.

Still, for many Americans, the June 1, 1921 massacre and the history of Tulsa's "Black Wall Street" neighborhood represented a gap in their knowledge of American history, at least until recently.

In fact, when a depiction of the massacre appeared in the opening scenes of 2019's "Watchmen", a popular fictional HBO series that debuted in October and drew from the real-life events of 1921, many viewers reported that they initially believed they were witnessing fictional events. Another fictional HBO show, "Lovecraft Country," also drew from the real-life massacre for a 2020 episode, further stoking the national conversation about an event that had once been seemingly ignored by history.

Historians say the history of "Black Wall Street" and the massacre that occurred there (much like the Juneteenth holiday) have generally not been taught in U.S. schools over the past century, even in Oklahoma, where the racist incident was only added to statewide school curriculums in February 2020.

Here's a look at how Tulsa's Greenwood District grew to become a haven for Black entrepreneurs at the beginning of the 20th century — and how 24 hours of racist violence destroyed much of what thousands of Black residents had built there, only for that tragic event and the people it affected to be unjustly ignored by history, for the most part, for decades afterward.

Entrepreneur O.W. Gurley and the founding of 'Black Wall Street'

Tulsa, in general, began to flourish around the turn of the 20th Century, thanks to a huge oil boom in Oklahoma. The area also saw a major uptick in Black settlers around that time, and leading up to Oklahoma's 1907 statehood, as land was readily available.

In 1906, a wealthy African-American land-owner, named O.W. Gurley, moved to Tulsa and bought 40 acres of land that he opted to only sell to Black settlers. Gurley had been born in Arkansas to former slaves and was mostly self-educated. Believing he was unlikely to experience success in the Jim Crow-era South, Gurley left Arkansas in the 1890s to join thousands of other homesteaders claiming land (which previously belonged to Native Americans but was made available by the federal government to westward traveling settlers).

Gurley initially established himself roughly 80 miles west of Tulsa, where he claimed a plot of land, became principal of the local school and ran a successful general store for more than a decade, according to Forbes. With the state's oil boom bringing newfound wealth to Tulsa in the early 1900s, Gurley moved to the city and bought the 40-acre plot that he and other Black entrepreneurs named Greenwood.

Gurley "had a vision to create something for black people by black people," author and historian Hannibal Johnson wrote in his book, "Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa's Historic Greenwood District."

In an interview, Johnson told Forbes that "Greenwood was perceived as a place to escape oppression—economic, social, political oppression—in the Deep South. It was an economy born of necessity. It wouldn't have existed had it not been for Jim Crow segregation and the inability of Black folks to participate to a substantial degree in the larger white-dominated economy."

Gurley loaned money to other black entrepreneurs looking to start their own businesses. This was important in establishing the Greenwood District as a center of Black business and wealth, as Black entrepreneurs would have otherwise had little to no opportunity to borrow money from white-owned banks during the Jim Crow Era. And, as Johnson points out, Gurley's push for Black-owned businesses was also a necessity in an era in America where intense racial segregation meant that Black citizens were often barred from patronizing many white-owned establishments.

One of Gurley's early business partners was J.B. Stradford, another son of former slaves who grew up to graduate from Oberlin College and obtain a law degree from Indiana Law School. After running a string of businesses in St. Louis, Stradford moved to Tulsa and built rental properties as well as the Stradford Hotel, which became a fixture on Greenwood Avenue.

The 54-room hotel was reportedly the largest black-owned and -operated hotel in America, and it featured a dining hall, gambling hall, saloon and regular Jazz performances for the neighborhood's residents. Forbes notes that Stradford's hotel, boosted by Greenwood's rising success, would eventually be valued at roughly $75,000 (or over $1 million in today's dollars) before it was destroyed in the violence of 1921.

Gurley himself also built a rooming house, multiple rental properties and his own hotel. He also owned a Masonic Lodge and a successful grocery store, which he supplied with produce from his nearby 80-acre farm. According to Forbes, as Greenwood's population grew, Gurley's fortune was ultimately worth roughly $200,000, equivalent to about $2.7 million today.

Other prominent Black business-owners in the area included John and Loula Williams, who owned a candy shop and built the neighborhood's Dreamland Theater, a 750-seat movie theater. There was also Andrew Smitherman, a lawyer who also founded and ran the Tulsa Star, one of the area's most prominent Black-owned newspapers.

The community even featured its own hospital and public library. Greenwood was a "modern, majestic, sophisticated, and unapologetically black" community, author Josie Pickens wrote for Ebony in 2013, adding that the neighborhood even had "a remarkable school system that superiorly educated black children."

By 1921, Tulsa's Greenwood District was one of the wealthiest Black communities in the U.S. and a center of Black wealth. The community of roughly 10,000 residents was thriving and supported Black-owned banks, restaurants, hotels, grocery stores and luxury shops, along with offices for Black lawyers and doctors. Because Tulsa was still very much racially segregated at the time, the Black residents mostly patronized Black-owned businesses, which helped the community thrive.

In fact, the community was so self-sustaining that it's now estimated that every dollar spent in the Greenwood District circulated within the neighborhood and its businesses at least 36 times, according to historians.

The district's success actually inspired Black author and orator Booker T. Washington to coin its nickname, which he originally called "Negro Wall Street," but which later became known as "Black Wall Street," according to the Greenwood Cultural Center.

That being said, the Greenwood District was far from a utopia. Even though many Black residents owned successful businesses and lived in relative luxury, historian Scott Ellsworth has pointed out that many others were poor and lived in "shanties and shacks."

The Tulsa massacre

Historians note that many of the Greenwood District's Black residents had moved to the area to escape the virulent racism of the Deep South.

However, while Greenwood's "Black Wall Street" was a self-sustaining enclave for Tulsa's Black community, it was also only blocks away from predominantly white neighborhoods that remained unwelcoming to their Black neighbors. What's more, racist violence was on the rise in the U.S. at the time. Just two years before the Tulsa Massacre, the nation endured the Red Summer of 1919, when at least 25 riots and incidents of mob violence erupted in major cities across the U.S., killing hundreds of people, most of whom were Black.

Those pre-existing racial tensions set the stage for a bloody day of racist violence that erupted over a nearly 24-hour period, ending June 1, 1921, after an armed white mob descended on the Greenwood District.

The mob attacked black residents and businesses in the neighborhood, leaving 35 city blocks "in charred ruins," according to the Tulsa Historical Society. In the skirmishes, as many as 300 people (mostly Black) were killed and hundreds more were injured, while thousands of Tulsa's black residents lost their homes and businesses.

The violence had been sparked by an incident in the preceding days involving a young African-American shoe-shiner named Dick Rowland, who rode in an elevator operated by a young white woman named Sarah Page. While reports of exactly what happened in the elevator vary, it is widely believed that Rowland accidentally came into contact with Page (perhaps stepping on her foot, or tripping and falling into her, according to different reports), causing her to scream.

One witness who heard the scream called the police, who eventually arrested Rowland on May 31. Meanwhile, after a Tulsa Tribune newspaper article falsely claimed that Rowland had assaulted Page, rumors about the incident ran wildly and some accounts even falsely claimed he had raped the woman, according to The New York Times. (Local law enforcement later admonished the Tribune for publishing an "untrue account" that helped to incite the violence, according to the Tulsa World.)

Tulsa's Black residents, fearing that Rowland would be lynched by an angry mob (a horrifically regular occurrence that's estimated to have happened thousands of times in the U.S. during the Jim Crow Era) after he received threats on his life, gathered in front of the city's courthouse where he was being held. A confrontation broke out between black and white groups at the courthouse, both of which were armed, resulting in shots being fired.

After that initial skirmish, Black residents retreated to the Greenwood District, while groups of white vigilantes reportedly spread throughout Tulsa attacking any Black people they encountered, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society. On the morning of June 1, a mob of over a thousand white people overran the affluent Black neighborhood, attacking and shooting residents.

The white mob looted and burned most of the neighborhood, firing on residents who tried to defend themselves but were outgunned by the attackers, some of whom reportedly had machine guns, surviving eyewitnesses later reported. Some survivors even said that the attackers flew over the area in private airplanes, from which they shot at Black residents and dropped firebombs on buildings.

The Oklahoma Historical Society reports that the violence trailed off later in the morning, upon the arrival of troops from the National Guard, though much of the neighborhood was already in ruins by that point. However, other reports suggest that the National Guard and the Tulsa police arrested Black residents instead of their attackers, and that some troops even joined in the attack, according to The New York Times.

In the end, more than 1,200 homes were reportedly burned, leaving most of the Greenwood District's 10,000 residents homeless. Over 6,000 of them were rounded up into internment camps by the local government and forced to live in tents, in some cases for months after the massacre.

In 2019, archaeologists in Tulsa discovered what they believed to be one site likely used as a mass grave to bury many of those who died in the massacre.

Meanwhile, Rowland was eventually exonerated, but an all-white grand jury decided not to charge any white residents in the wake of the violence, which mostly blamed on Black residents, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

For many years after the massacre, there was some argument over whether the incident should be referred to as a massacre or a "riot." Early reports referred to the incident as the "Tulsa Race Riot," with the Tulsa Historical Society noting that such terminology may have been used for insurance purposes, as a riot would not have required insurance companies to pay out benefits to Black residents whose homes and businesses were burned.

The Greenwood District after the massacre

The Greenwood District was eventually rebuilt by Black residents who refused to leave the city, starting immediately after the massacre, with hundreds of structures rebuilt by the end of 1921. By 1925, Greenwood hosted the annual conference of Booker T. Washington's National Negro Business League and, by 1942, the neighborhood boasted more than 200 Black-owned businesses, according to a report from the state's 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Centennial Commission.

Still, many of the neighborhood's surviving Black residents never fully recovered the wealth that was lost amid the looting and destruction.

"For years, black women would see white women walking down the street in their jewelry and snatch it off," John W. Franklin of the National Museum of African American History and Culture said in 2016.

As for individual entrepreneurs, Gurley and Stradford reportedly lost their fortunes in the violence and destruction, and both left Tulsa. Stradford moved to Chicago, where he set up a successful law practice. Gurley moved to Los Angeles, where little is known of what he did before he died in 1935.

Smitherman's newspaper press, business and home were all destroyed in the massacre. He left Tulsa after, fleeing to Massachusetts while reportedly facing some blame from Tulsa authorities for inciting the violence because his newspaper advocated for Black Americans to arm themselves and stand up for their rights.

The Dreamland Theater was rebuilt by the community after the massacre, but the theater and many of the rebuilt neighborhood's businesses eventually shut down a few decades later. As Tulsa neared the mid-century mark, increasing integration across the country meant that Black residents no longer needed to only spend their money at Black-owned businesses, which sent money outside of the community. What's more, Tulsa (like many other U.S. cities) committed to "urban renewal" plans in the 1960s and '70s that razed much of the Greenwood District to make way for public works projects, including construction of a major highway in the 1960s that cut right through the neighborhood.

Today, the district's main thoroughfare, Greenwood Avenue, cuts through the Tulsa campus of Oklahoma State University.

In 2001, an Oklahoma state commission to study the 1921 massacre delivered a fact-finding report meant to officially recognize the tragic event after decades of it being ignored by the local government. The commission determined that some form of reparations should be made to the massacre's survivors and their descendants. However, a federal judge ruled against the commission's calls for reparations in a 2004 ruling, and groups of survivors, as well as the Human Rights Watch, are still calling on the government to offer some sort of reparations to the massacre's survivors.

In 2010, the city dedicated a park, called the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park after an African-American historian from Tulsa, in the memory of the victims of the 1921 Tulsa massacre. In 2020, the federal government recognized the park as an official member of the African American Civil Rights Network. This week, a walkway called the "Pathway to Hope," connecting the park to the Greenwood District, will be dedicated during a slate of events commemorating the massacre's centennial.

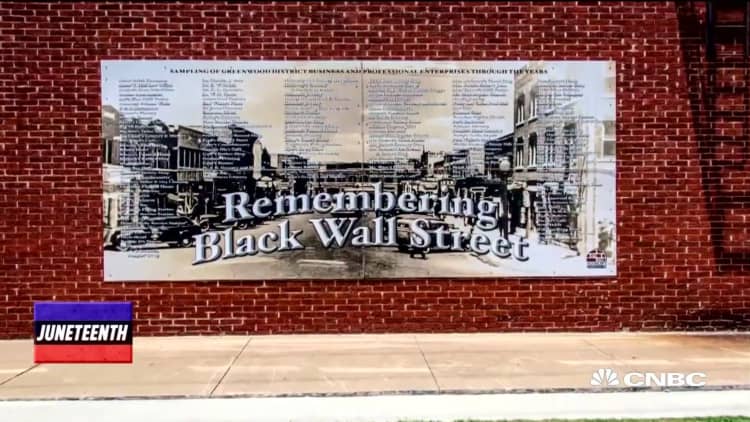

In 2018, local officials also dedicated a "Black Wall Street" mural painted on one side of the highway that now runs through the Greenwood District. And, local leaders worked to secure $25 million in funding for the Greenwood Rising History Center, a museum offering educational programs about the district's history, which will officially open this week, in time for the massacre's 100th anniversary.

Meanwhile, further efforts remain underway to restore the area once known as "Black Wall Street" today. Last year, multiple community organizations worked together to restore the Tulsa home of 105-year-old Lessie Benningfield Randle, who is one of the few remaining survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Massacre. And, the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce is actively seeking to raise up to $10 million to restore and rebuild the district through a campaign called Restore Black Wall Street.

Check out: The best credit cards of 2020 could earn you over $1,000 in 5 years

Don't miss:

Juneteenth: The 155-year-old holiday's history explained

5 ways to start being a better ally for your Black coworkers