In 2017, a man claiming to be a member of the ultra-wealthy Saudi royal family, named Prince Khalid Bin Al-Saud, entered into talks with real estate developers to make a $400 million investment in an iconic luxury hotel on Miami Beach.

He certainly looked the part of rich royalty. For starters, the "prince" lived in the penthouse condo of a luxury high-rise — he claimed to own the whole building — on Fisher Island, the exclusive private island neighborhood located just off the coast of Miami. (With celebrity residents that have included Oprah Winfrey and Andre Agassi, the island boasts the richest zip code in the U.S., with an average income of $2.5 million as of 2015.)

Khalid regularly drove around the luxury enclave in a 2016 Ferrari California (with a base price of roughly $200,000) sporting diplomatic license plates and a security detail. He was also known to ride around in other luxury vehicles, from a Bentley to a Rolls Royce, while traveling on yachts and private jets.

And Khalid made sure to document his fabulous lifestyle on social media, posting photos on Instagram showing off his luxury vehicles, diamond-encrusted jewelry, Rolex watches. His Instagram profile, under the screen-name "@princedubai_07", also showed the lengths to which Khalid would go to spoil his prized chihuahua, Foxy, whom he carried around in a nearly $2,700 Louis Vuitton dog carrier.

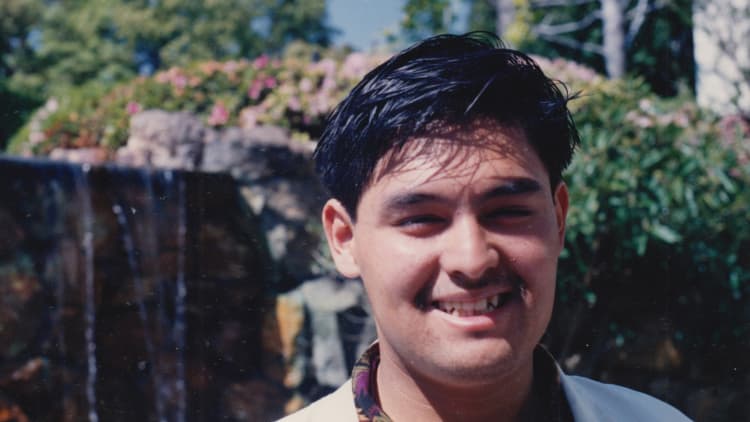

There was just one problem: The man calling himself Prince Khalid Bin Al-Saud — to his wealthy neighbors and business partners who had handed him millions of dollars in investments — was actually a con-man named Anthony Gignac. Far from being a member of the Saudi royal family (which has an estimated net worth of more than $1 trillion), Gignac was actually born in Colombia and moved to Michigan at age 6, when he and his brother were adopted by a middle-class couple.

But as federal prosecutors would later explain, Gignac did not have anywhere close to the hundreds of millions of dollars he claimed to hold in foreign bank accounts. He also didn't own the Fisher Island high-rise and all 54 of its luxury condos, but was in fact merely leasing the building's penthouse. Even the diplomatic license plates were fake, with Gignac's business partner having purchased them on eBay, according to Vanity Fair.

In March 2019, then 48-year-old Gignac pleaded guilty to charges of impersonating a foreign diplomat, aggravated identity theft, wire fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud. Two months later, he was sentenced to more than 18 years in federal prison.

Gignac's multimillion-dollar fraud scheme is the subject of the season premiere of CNBC's "American Greed," titled "The Fake Prince's Royal Scam," airing Monday, Jan. 6 at 10 pm ET.

How he duped investors

Rather than living off a vast royal fortune, Gignac had been funding his lavish lifestyle with money he bilked from investors, who believed he was an actual Saudi prince with a significant stake in Saudi Aramco, the oil giant controlled by the real Saudi royal family.

Gignac had managed to build a network of investors around the world with his royal ruse by offering to sell pieces of his fake Saudi Aramco stake at a discount ahead of the company's planned IPO, according to a criminal complaint filed against Gignac in 2017 by federal authorities. Gignac also offered opportunities to invest in other imaginary businesses, such as a platform for trading jet fuel, a casino in Malta and an Irish pharmaceutical company.

Saudi Aramco eventually did go public in December 2019 at a valuation over $1.8 trillion, making it the world's most valuable public company.

Had Gignac's investment offers been legitimate, his business partners might have stood to make a lot of money. In fact, Gignac told investors they could make "five times" their initial investments once the company went public. Instead, federal authorities said he collected nearly $8 million from those investors and used that money to maintain his flashy lifestyle and buy the very luxury goods that would help him pass as a member of one of the world's richest families.

"Those funds were not put into business opportunities, legitimate investments, or any interest-yielding source," the Department of Justice said in a statement in May 2019. "Instead, Gignac used the money to finance his lavish lifestyle, including Ferraris, Rolls-Royces, yachts, expensive jewelry, designer clothing, travel on private jets, and a two-bedroom property on Fisher Island. Investors were also tricked into giving Gignac extravagant gifts like paintings, jewelry, and memorabilia."

In order to sell his con to those investors, Gignac did more than just dress the part, wearing expensive jewelry such as diamond rings, Cartier bracelets and Rolex watches, as well as traditional Middle Eastern garments like a white thobe and a red-and-white ghutra headdress. According to court documents, he also bought the fake diplomatic license plates for his luxury cars and fabricated documents with names of law firms and banks associated with the real Saudi royal family in order to make his claims of wealth and status seem legitimate.

"The idea that you could buy a good portion of that company, which is valued at $2 trillion, at a discounted rate … An outstanding return of investment is something that lured a lot of people to Mr. Gignac," Diplomatic Secret Service special agent Ryan McSeveney told CNBC in an interview for "American Greed."

Who is Anthony Gignac?

To be fair, Gignac had also been honing his scheme for much of his life.

Starting in 1988, Gignac was arrested or convicted 11 times for schemes where he was impersonating a prince or other Middle Eastern royalty, according to the U.S. Justice Department.

After leaving his adoptive family in Michigan as a teenager, Gignac began using stolen credit cards to cruise around Detroit in limousines while trying to pass himself off as "Prince Adnan Khashoggi," using the name of a billionaire Saudi arms dealer, according to Vanity Fair.

Gignac eventually took his act to California, where in 1991 The Los Angeles Times dubbed him the "Prince of Fraud" after the then 21-year-old racked up nearly $3,500 in room and food bills at the Regent Beverly Wilshire Hotel, along with another $7,500 in limousine charges and more fraudulent purchases of Louis Vuitton luggage from Rodeo Drive shops. Gignac had promised that his wealthy family would pay off his debts — even convincing the tony hotel's employees to refer to him as "Your Highness" — but he was eventually arrested and sentenced to two years in prison.

"He was very audacious, he was very bold, and he was very aggressive," McSeveney tells "American Greed." Gignac often pulled off his cons by being loud and aggressive, angrily yelling at anyone who challenged his identity, asking: "Do you know who my parents are?"

"Nobody would really believe that if you were faking this that you would draw that much attention to yourself, and scream and yell," Trinity Jordan, a former Assistant U.S. Attorney in Florida's Southern District, tells CNBC. "Because it's so bold, and opposite what you normally would expect a con-man to do, it's probably why it worked."

Gignac continued pulling off relatively small-scale cons throughout the 1990s and 2000s, using forged documents to con credit card companies into giving him cards under the name Khalid Bin Al-Saud. He then maxed out those cards running up bills worth tens of thousands of dollars at hotels and upscale retailers across the country.

In 1993, Gignac traveled to Hawaii, where he pretended to be a prince and scammed tourists out of nearly $30,000 to cover his stay at a luxurious resort by falsely claiming he could offer them a stake in an oil field in Saudi Arabia, according to Vanity Fair, which cites court documents. He pulled similar frauds in Florida, running up tens of thousands of dollars in credit card debt at high-end resorts, such as the Walt Disney World Grand Floridian Beach Resort in Orlando, as well as more than $51,000 at a Florida Saks Fifth Avenue location.

Over the years, those sort of schemes landed Gignac in and out of prison for charges ranging from fraud and grand theft to impersonating a foreign diplomat. In some cases, Gignac even kept up the ruse while on parole or while out on bail, including one instance in the early 1990s when he was awaiting trial on fraud and grand theft charges in Florida, and Gignac convinced American Express to issue him a Platinum card with a $200 million line of credit. (The Miami Herald reports that Gignac secured the card by falsely claiming he'd lost an existing Platinum card and then screaming at skeptical American Express employees that his father, the king, would be furious if his card wasn't replaced.)

He booked a limousine and immediately went to a jeweler, where he spent over $22,000 on two Rolex watches and an emerald and diamond bracelet.

In 2003, Gignac was arrested again back in Michigan and charged with defrauding high-end department stores Neiman Marcus and Saks Fifth Avenue out of $29,000 in clothing, jewelry and perfume, including Chanel fragrances, Brioni shirts and Salvatore Ferragamo shoes. At the time, authorities said Gignac had told store employees that he was a Saudi prince worth nearly half a billion dollars. He faced up to four years in prison.

In that case, Gignac even allegedly charged thousands of dollars to a Neiman Marcus account owned by an actual Saudi prince, though authorities were unsure how Gignac actually managed to acquire the real prince's account number, former Oakland County, Michigan prosecutor Gerry Gleeson told CNBC's "American Greed."

Gignac told authorities at the time that he actually knew the Saudi royal family and that he was using the real prince's account with the family's permission. Gignac claimed he'd had an affair with the real Saudi prince and that the family was supporting him financially to keep him silent.

An assistant to the U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia told federal officials in 2003 that Gignac was "not a member of the Royal Family nor associated in any way with the Saudi Royal Family," and the actual Prince Khalid sent a letter to Neiman Marcus claiming he did not know Gignac, Vanity Fair reported in 2018.

Gignac pleaded guilty to attempted bank fraud and impersonating a foreign diplomat in 2006, receiving a sentence of 77 months in federal prison.

How he got caught (again)

But rather than pulling back from his fraudulent schemes as a result of being caught over and over again, Gignac would eventually ramp up his con to new extremes. Instead of scamming hotels and retailers out of tens of thousands of dollars, Gignac set his sights higher.

Again posing as a Saudi prince, he met a British asset manager named Carl Marden Williamson who helped Gignac establish connections with deep-pocketed investors around the world, with the "prince" offering at first to put up his own money for investments but ultimately seeking large investments for his own imaginary business opportunities. (According to federal authorities, Williamson was in on Gignac's scheme and he was named as Gignac's co-conspirator in the federal case. However, Williamson died following a reported suicide attempt shortly after being interrogated by federal agents in connection with the case.)

Through that ruse, Gignac reaped millions of dollars from unsuspecting investors. But the much larger scale of his new scheme also increased the risk of exposure.

In 2017, Gignac connected with real estate developers looking for a deep-pocketed investor to buy a significant stake in the Fontainebleau Miami Beach hotel. But over the course of those deal talks, the developers started engaging in due diligence that raised questions over the supposed Saudi prince's identity. When those developers reported their suspicions to the FBI, federal authorities quickly recognized Gignac's handiwork — and this time, they realized that his usual cons had grown to include massive financial fraud.

Upon his arrest in 2017, DSS agents seized jewelry from Gignac worth an estimated $450,000 in total, along with $80,000 dollars in cash and various pieces of artwork, such as an autographed photograph of boxing legend Muhammad Ali.

"The entire blame of this entire operation is on me, and I accept that," Gignac told a federal judge at his 2019 sentencing in Miami, according to The Miami Herald. But, he added, "I am not a monster."

Watch all new episodes of CNBC's "American Greed″ on Mondays at 10 p.m. ET/PT.

Don't Miss:

How an ex basketball coach tried to pull off the biggest college admissions scam ever

'Nigerian prince' email scams still rake in over $700,000 a year—here's how to protect yourself

Like this story? Subscribe to CNBC Make It on YouTube!