Bitcoins act like cash, but they are mined like gold. So how does someone get into the current bitcoin rush?

If properly done and willing to take the investment risk, you could wind up with a few bitcoins of your own—which currently have an average weekly price of $945 on the largest bitcoin exchange.

Here's how it's done.

How many bitcoins are there?

When the algorithm was created under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto—which in Japanese is as common a name as Steve Smith—the individual(s) set a finite limit on the number of bitcoins that will ever exist: 21 million. Currently, more than 12 million are in circulation. That means that a little less than 9 million bitcoins are waiting to be discovered.

Since 2009, the number of bitcoins mined has skyrocketed. That's the way the system was set up—easy to mine in the beginning, and harder as we approach that 21 millionth bitcoin. At the current rate of creation, the final bitcoin will be mined in the year 2140.

(Read more: What is bitcoin?)

What exactly is mining?

There are three primary ways to obtain bitcoins: buying on an exchange, accepting them for goods and services, and mining new ones. "Mining" is lingo for the discovery of new bitcoins—just like finding gold. In reality, it's simply the verification of bitcoin transactions.

For example, Eric buys a TV from Nicole with a bitcoin. In order to make sure his bitcoin is a genuine bitcoin, miners begin to verify the transaction.

It's not just one transaction individuals are trying to verify; it's many. All the transactions are gathered into boxes with a virtual padlock on them—called "block chains."

Miners run software to find the key that will open that padlock.

Once their computer finds it, the box pops open and the transactions are verified. For finding that "needle in a haystack" key, the miner gets a reward of 25 newly generated bitcoins.

The current number of attempts it takes to find the correct key is around 1,789,546,951.05, according to Blockchain.info—a top site for the latest real-time bitcoin transactions.

Despite that many attempts, the 25-bitcoin reward is given out about every 10 minutes. In 2017, the bitcoin reward for verifying transactions will halve to 12.5 new bitcoins and will continue to do so every four years.

(Read more: Why the Internet may never be the same again)

How do you mine on a budget?

Bitcoin mining can be done by a computer novice—requiring basic software and specialized hardware.

The software required to mine is straightforward to use and open source—meaning free to download and run.

A prospective miner needs a bitcoin wallet—an encrypted online bank account—to hold what is earned. The problem is, as in most bitcoin scenarios, wallets are unregulated and prone to attacks. Late last year, hackers staged a bitcoin heist in which they stole some $1.2 million worth of the currency from the site Inputs.io. When bitcoins are lost or stolen they are completely gone, just like cash. With no central bank backing your bitcoins, there is no possible way to recoup your loses.

The second piece of software needed is the mining software itself—the most popular is called GUIMiner. When launched, the program begins to mine on its own—looking for the magic combination that will open that padlock to the block of transactions. The program keeps running and the faster and more powerful a miner's PC is, the faster the miner will start generating bitcoins.

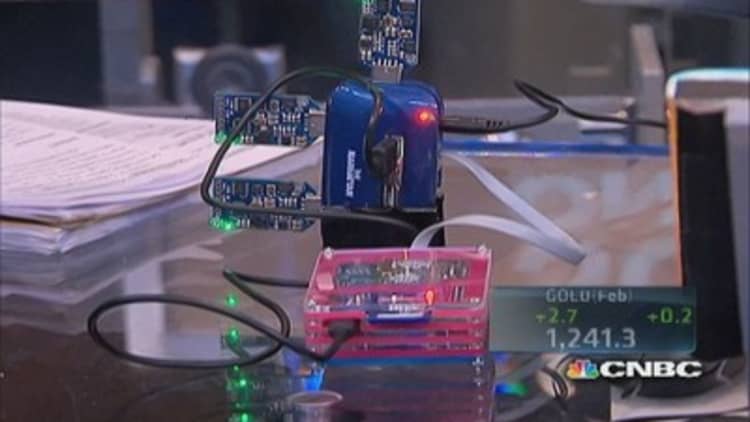

When mining began, regular off-the-shelf PCs were fast enough to generate bitcoins. That's the way the system was set up—easier to mine in the beginning, harder to mine as more bitcoins are generated. Over the last few years, miners have had to move on to faster hardware in order to keep generating new bitcoins. Today, application-specific integrated circuits (ASIC) are being used. Programmer language aside, all this means is that the hardware is designed for one specific task—in this case mining.

New faster hardware is being created by various mining start-ups at a rapid rate and the price tag for a full mining rig—capable of discovering new bitcoins on its own—currently costs in the ballpark of $12,000.

(Read more: How to make your email as stealth as Edward Snowden)

There is a way around such a hefty investment: joining mining pools. Pools are a collective group of bitcoin miners from around the globe who literally pool their computer power together to mine. Popular sites such as Slush's Pool allow small-time miners to receive percentages of bitcoins when they add their computer power to the group.

The faster your computer can mine and the more power it is contributing to the pool, the larger percentage of bitcoins received. Bitcoins can be broken down into eight decimal points. Like wallets, pool sites are unregulated and the operator of the pool—who receives all the coins mined—is under no legal obligation to give everyone their cut.

Joining a pool means you can also use cheaper hardware. USB ASIC miners—which plug into any standard USB port—cost as little as $20. "For a few hundred dollars you could make a couple of dollars a day," according to Brice Colbert, a North Carolina-based miner of cryptocurrencies and operator of the site cryptojunky.com. "You're not going to make a lot of money off of it and with low-grade ASICs you could lose money depending on the exchange rate."

The other way you could lose money when it comes to mining is power consumption. Currently, profits outweigh money spent on the energy needed to mine. Again, that could quickly change due to the volatile price of bitcoin.

"It's time sensitive, like a yo-yo", said Jeff Garzik, a Bitcoin developer for the payment processor BitPay. It's not mining or investors that are causing the radical highs and lows in the currency's value, it's the media, he said. "Bitcoin's price tends to follow media cycles, not hardware or mining. The difficulty in mining is not the highest correlation in bitcoin value."

—By Anthony Volastro, CNBC Segment Producer