He lived awfully close to Langley, Virginia for nearly 20 years, was backed by the Central Intelligence Agency in the mid 1980s, and suddenly, less than two weeks ago, amassed an army and air force and seemed to be gaining the upper hand in war-torn Libya.

General Khalifa Haftar, once scorned in the North African country, is now the man to watch after starting a massive military offensive little more than a week ago with the apparent backing of the country's air force and a Twitter hash tag to boot.

"I am quite surprised. We assessed him to be a marginal person," said Frederic Wehrey, senior associate for the Middle East at the Carnegie Endowment.

"Everyone laughed at him. He was a running joke" after a failed coup attempt in February, leading to tweeters in Libya "making fun of him," Wehrey said.

"We thought he went into oblivion," said Karim Mezran of the Atlantic Council, "He surprised everyone."

Read More

On May 16, Haftar launched his assault in Benghazi, with the stated aim of wiping out Islamic extremist militias in control of parts of the city. Two days later, he claimed responsibility for an attack on the country's Parliament—which he, like many, calls illegitimate—in the capital of Tripoli. The Associated Press reported more than 50 died in the clashes, some of the heaviest since the fall of dictator Moammar Gadhafi in 2011.

Even before the assault, the continuing inter-militia, warlord-style conflict in the country has punished the country's once-prosperous oil industry. Production has plunged to less than 200,000 barrels per day, down from 1.4 million in 2011.

Haftar has labeled his offensive as "Operation Libyan Dignity" and late last week people claiming to be supporters of his staged rallies in Tripoli and Benghazi carrying signs saying "Yes to Dignity" and "Libya restores Dignity." The Twitter campaign is using #LibyaDignity.

"He has been a good marketer," Mezran said.

Haftar has described his battle in "a context of a good secularist against extreme Islamists."

Read More

Wehrey at the Carnegie Foundation said Haftar seems to be modeling himself on General Abdel Fatah al-Sisi of Egypt, portraying himself "as a strongman in uniform who claims to be ridding out terrorism."

Libya expert Omar Turbi said that within Libya "there is a great deal of support for what (Haftar) is doing," because he has "scared the heck out of the extremists." But Turbi doesn't believe Haftar can ultimately lead the county.

"He's tempted to do an al-Sisi situation, but he's not going to be accepted. They lived with a dictator for 40 years. You think they're going to accept that again? Not going to happen."

When it comes to the energy markets, the focus is on whether Haftar could stabilize the country enough in order for oil production to resume to its previous levels.

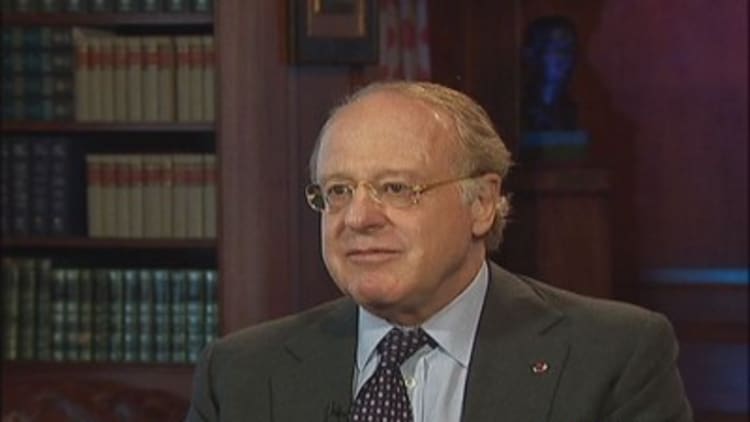

Paolo Scaroni, former CEO of Italian oil giant ENI, calls the situation in Libya "the last battle."

Of all the oil majors, ENI has the largest prescense in Libya. Scaroni, who traveled extensively to Libya while CEO, said that up until now the battles in Libya have been between regional factions and militias.

"Now the major battle is ideological and political" and the country may finally make a choice between parties like the Muslim brotherhood, or a more secular, less extremist, path, he said.

In October, Scaroni told CNBC (see video) that Libya has the potential to pump two million barrels of oil per day if it could finally achieve stability. Back then he noted "five million people and two million barrels of oil (per day), which means that this country can be a paradise, and I am doubtful that Libyans will not catch this opportunity of becoming the new Abu Dhabi, or the new Qatar or the new Kuwait."

But when?

There is great debate in Libya, Europe and Washington about whether Haftar has the support of the CIA.

Executives familiar with the Libyan oil industry say it is widely assumed the CIA is once again involved with Haftar. But neither Mezran, Wehrey or Turbi believe that to be the case.

Numerous accounts suggest he was spirited out of North Africa by the CIA after a failed attempt to overthrow Gadhafi in the 1980s. He lived in Virginia until 2011 when he returned to Libya to help lead the opposition against Gadhafi.

"I don't think the CIA is backing him now," Mezra said.