Maybe this is what happens when a central bank becomes too transparent.

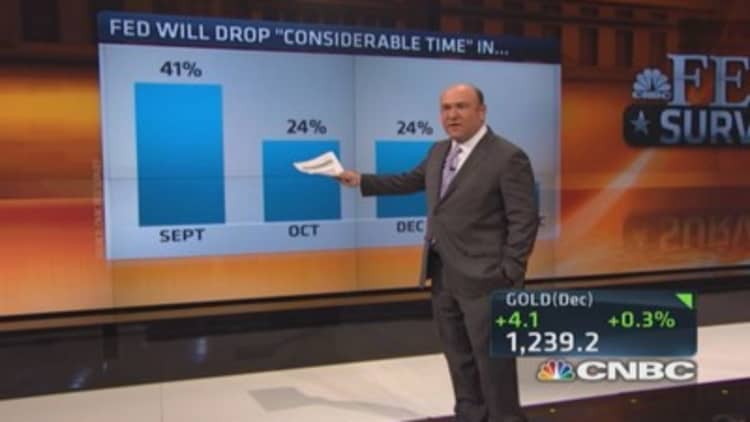

After years of nearly complete clarity regarding policy, the Federal Reserve suddenly has investors and economists scrambling to decipher whether just a few words will be removed or changed in a statement Wednesday that likely will run about 850 words in total.

Should those words—"a considerable time," in particular—go away, most market participants believe that will signal a hike in interest rates sooner than the market had expected. Should they stay, conversely, that will mean the U.S. central bank will stay on a path of near-zero short-term rates well into the future, and maybe even beyond current market expectations.

Consequently, Fed Chair Janet Yellen has fashioned quite a tightrope to walk when the Open Market Committee delivers its post-meeting statement, and when she follows with an afternoon news conference.

Investors have taken note of all the uncertainty, boosting interest rates and selling stocks until they get more monetary policy clarity.

Read MoreWall Street view on Fed rate hikes changing

"The way they change the language is going to be instrumental," Quincy Krosby, chief market strategist at Prudential Annuities, said Tuesday as the FOMC began its two-day meeting. "They're probably sitting there with a thesaurus making sure that if they dial it down just a little bit that they don't cause a major disturbance in the market."

Here is the critical paragraph many on Wall Street have in focus:

The Committee continues to anticipate, based on its assessment of these factors, that it likely will be appropriate to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends, especially if projected inflation continues to run below the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal, and provided that longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored.

What worries the market can be summed up in the punch bowl analogy: If the Fed indicates it will be refilling the punch bowl i.e., keeping the language intact even after the monthly bond purchases—quantitative easing—end in October, then the market may just go on its merry way and keep the 2014 rally intact, despite a rough September. (The is up 7.4 percent for the year, but down 0.9 percent in September.)

However, should it choose to remove the language or alter it, that could jolt the market into realizing that it's at least last call for the Fed punch bowl, even if the party will still continue a while. The dynamic was at play Tuesday, when the market rallied off a Wall Street Journal report indicating that there would be little change in the FOMC statement.

Yellen "knows the market wants an update," Krosby said. "She is going to give us an update, but I don't think it's something that's going to shock the market."

Read MorePimco exec: The Fed HAD to pump up the market

The trigger for all the speculation was a paper from two San Francisco Fed economists indicating that tightness in the labor market and improving economic data likely would push the FOMC to pare the "extended period" language from the statement. The paper asserted that market expectations for rates lagged Fed expectations.

But many Wall Street pros remain unconvinced. Economists Ethan Harris at Bank of America Merrill Lynch and Jan Hatzius at Goldman Sachs both issued notes in recent days strongly doubting the Fed is ready to change its language and thus accelerate the timeline for a rate increase.

Harris said those watching the Fed "dot plot"—essentially a graph indicating future rate expectations—are also placing too much emphasis on forecasts, and instead should listen to Yellen and the committee's words and heed their strongly dovish bias.

"Janet Yellen is a first among equals and hence her dot should get extra weight," Harris said. "It is understandable that two staff economists would want to ignore these inconvenient truths, and take the dot plot at face value, but putting differential weights on the dots is essential to forecasting Fed policy."

BofAML did bring forward its expectations for a rate increase from September 2015, but only to June. Should the Fed remove "extended period," that would suggest an increase as soon as March, based on earlier Yellen statements.

Read MoreWall Street sees Fed hike sooner: CNBC survey

Capital Economics is in the camp that sees a March increase, but for reasons outside the "dot plot" or "extended period" language. Rather, economist Julian Jessop sees wage and cost pressures as the biggest influences.

But there's even more to consider: Peter Boockvar, chief market analyst at The Lindsey Group, said the speculation over both issues is misplaced, and what the market really should watch is whether the Fed adjusts its assessment of the employment situation as involving "significant underutilization of labor resources." It's a new phrase for the FOMC and its inclusion indicates a dovish bent on the belief that there remains plenty of slack in the labor market that the Fed can help with low rates.

Another slightly out-of-consensus view comes from Deutsche Bank economist Joe LaVorgna, who expects the "considerable time" language to be removed, but only as a signal that the Fed will "replace calendar-based guidance with a more-data driven approach" for when it will raise rates, and not an accelerated schedule.

All of this speculation, of course, is exactly what the Fed doesn't want, but it is what it gets in a world where an entity known for its clarity suddenly finds itself in murky waters with investors trying to parse the meaning of phrases and dots.

Read MoreWhy investors may get a rude awakening: Siegel

"If 'significant underutilization' comes out it may say more about actual timing more so than the obsession of 'considerable time,'" Boockvar said in a note.

Taking the diverging speculation together, it's enough to make some pine for the days before Alan Greenspan, when the Fed didn't even release statements other than what it was doing with rates.

"The market will get over this. Ultimately we'll go back to regular news," Prudential's Krosby said. "The market doesn't get weighed down on anything. It gets upset, it gets volatile, and it moves on."

—By CNBC's Jeff Cox