In the best of all worlds, as the Fed moves to raise interest rates, short-term bond yields that impact things like consumer loans would rise gradually, and longer-term rates affecting mortgages would rise more slowly.

Markets got a little taste of that Wednesday when short-term rates rose with the dollar and stocks in response to the Fed. The bond market clearly heard a hawkish central bank Wednesday, expecting slightly more aggressive rate hikes next year and beyond.

But the Fed did not remove dovish language in its statement so stocks moved higher too, interpreting the central bank to be committed to easy policy for quite a while. Some strategists have been looking for a great rotation out of bonds, when the Fed finally signals rate hikes, driving investors to dump bonds en masse.

But BlackRock's Jeffrey Rosenberg says it's another type of rotation that could occur and the response to the Fed's meeting Wednesday was a glimpse of it. Investors may sell the short end, driving yields higher, and stay with the longer end, keeping a lid on long-term rates, which impact mortgages and other longer duration loans.

"I wouldn't say it's off to the races" for that trade, said Rosenberg, BlackRock's chief investment strategist for fixed income. He said investors will find they need fixed income in their portfolios to hedge risk assets, and rising rates won't make them abandon the bond market.

"The big move in the market (Wednesday) was five-year real rates that went up 15 basis points. This is the market reacting to normalization," he said. Yields continued to rise Thursday, with the five-year yielding 1.85 percent but the two-year retraced some of its move. The 10-year yield also moved slightly higher—to 2.62 percent.

Read MoreWhy stocks and bonds see the Fed differently

Rosenberg said the Fed helped pave the way for market perception Wednesday, but Fed Chair Janet Yellen added to it when she re-emphasized that the central bank will continue to replace the longer duration Treasurys on its balance sheet as they mature, at least until it hikes rates.

That should help keep down yields at the long end, and the 10-year is particularly key to the economy since it affects the rates on home mortgages. "The impact on the real economy at the front end of the curve can be small. This is why holding down the long end is key," he said.

The prospects of Fed tightening have been showing up in the market for a while, and evidence of that is the race to issue new corporate debt this month. "The month of September has already seen over $90 billion, just investment grade, which puts it on a pace to potentially be the largest month of corporate bond issuance in history," said Edward Marrinan, head of macro credit strategy at RBS.

Marrinan said he thinks the pace of issuance, however, could slow a bit now that the Fed meeting and the European Central Bank's new lending facility are out of the way.

Read More

The big fear in markets is that the Fed will not make it to liftoff smoothly, and its march toward high rates will jar markets. While Marrinan said he expects more volatility as the central bank gets closer to hiking rates, he said the slow-growing economy is giving the Fed more cover to manage the process than if the economy was growing by leaps and bounds.

"What the Fed is trying to do is minimize this five-year investment in ZIRP (zero interest rates) and QE (quantitative easing) for the benefit of the economy," he said. "And then undertake a very deliberate and well telegraphed process of not just withdrawing stimulus but undertaking tightening."

The fact that the bond market has been so skewed toward Fed dovishness—easy policy—makes the process even more difficult, he said.

Read MoreHere's what changed in new Fed statement

Bank of America Merrill Lynch credit strategists also weighed in on the Fed, saying it guided interest rates higher, but at the same time rate uncertainties lower.

"Such outcome is positive for risk assets—especially credit, and especially financials—in the short term. Rising interest rates reflecting an improving economy is great, as long as the process is gradual," they wrote.

So it's not that surprising that the Fed, while seeing higher rates, also sees a slower pace of growth out to 2017.

In its forecast, the Fed saw higher growth next year, but its outlook then trails off after that. The forecast had been for 2.5 to 3 percent for 2016. but that was reduced to 2.4 to 2.5 percent, and the central bank sees an even slower pace of growth in 2017—2 to 2.3 percent.

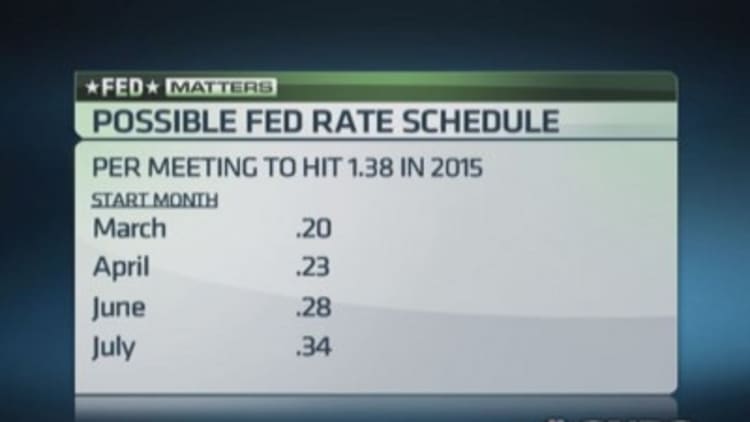

The central bank slightly changed its forecasts for rate hikes Wednesday. For the end of next year, the median projections of Fed officials for the fed funds rate was 1.375 percent compared with 1.125 percent in June, and the projection for the end of 2016 moved up to 2.875 percent from 2.50 percent.

"If the Fed continues to guide interest rates up and uncertainties down the process of monetary policy normalization can look like 2004, and see continued rallies in risk assets. However, as Chair Yellen also made very clear, the Fed is completely data dependent. In other words the economy—and less so the Fed—is going drive the future path of monetary policy. The coming tightening cycle is only going to be benign for risk assets if the economy proceeds like in 2004, i.e., a weak, jobless, recovery. If the economy is strong, and resumes the path of strong jobs creation, the situation would be much more disorderly in rates and for risk assets—like in 1994—and there will be little the Fed can do about it," the BofAML strategists wrote.

While some market players were confused, strategists said the move up in short-term yields, higher stocks, lower gold prices and a firmer dollar made sense.

"It shows that the market is taking the Fed's information on board as the thinking has evolved at the FOMC about the timing and pace of hikes, along with their guidance on the economic data," Marrinan said, While most economists don't expect liftoff, or the first rate hike until mid-2015, the market has been reacting to the idea rates could move higher, and positive economic reports reinforce the idea.

"There's probably more bear flattening to come," Marrinan said. "The front end rates will rise at a pace faster than the long end, and that will help flatten the Treasury curve from front end up." Flattening is when the shorter duration yields get closer to the longer duration yields, and it is a sign of higher rate environment."

But Ward McCarthy, chief financial economist at Jefferies, warns the first rate hike may still be a year away, and the economy and inflation may not cooperate with the Fed.

"I think we're going to be over a year from it yet," he said. "Inflation is going to determine when the Fed starts to raise rates, and the first barometer of when that's going to happen is the ability of commodities prices to sustain a firmer bid because that will signal global growth is strong enough."

One problem for the Fed could be the strengthening dollar, with the potential to hurt U.S. exports, overseas corporate profits and pressure commodities prices.

But Deutsche Bank's chief U.S. economist, Joseph LaVorgna, said relatively speaking, the dollar gains are modest, with the trade-weighted dollar up only 6 percent from its all-time low set in July 2011.

"Furthermore, over the past 12 months, the real broad trade-weighted dollar is up a scant 0.3 percent. At its current inflation-adjusted level, relative to the United States' major trading partners, the dollar remains historically weak, not strong. Consequently, we should not be concerned at this point that a strengthening dollar is going to adversely impact U.S. export performance, or that it is going to lead renewed downward pressure on core inflation," LaVorgna wrote.

McCarthy agrees the Fed is clearly walking the markets toward higher rates. "There's a lot of moving parts that came out yesterday, and the big picture is the Fed is a long way from starting to raise rates from a historical stand point, or a dual mandate stand point. Either way they want to avoid financial market excess," he said. So what the Fed is signalling—"they're indicating the cost of money is going up."

Marrinan said it's not clear when the Fed will raise rates, but it's pushing market expectations forward. "I think the outcome will be volatility," he said. "I think any transition to new policy regime will come with bumps. They recognize it's not going to be perfect, but they hope to get as close to that objective as they can get."

—By CNBC's Patti Domm