A new business plan has two Israeli doctors hoping for big changes when it comes to reducing joint pain. Their at-home system, Apos Therapy, is non-invasive and it's caught the attention of former pro athletes.

Tom "Satch" Sanders, now 76-years-old, played 13 seasons with the NBA's Boston Celtics in the 1960s and '70s, winning eight championships. He's one of a group of Professional Basketball Alumni Association players that are trying Apos Therapy.

Sanders suffers from sciatica, a condition that causes pain down the lower back and legs. After walking in Apos' boots last summer, Sanders says relief came almost immediately.

"I thought it was kind of unbelievable that the second time I wore them, I told my wife, I said, 'You know, something strange has occurred. I'm not feeling the kind of pain that I felt with the sciatica, and it's gotta be the shoes." Sanders said.

How it works

It's called Apos because it works during all-phases-of-the-step cycle, focusing specifically on the muscles and nervous system. Doctors Avi Elbaz and Amit Mor began working on the system back in the 1990s when they were students at an Israeli medical school.

Read MoreDNA vaccine hunters aim to cure cancer

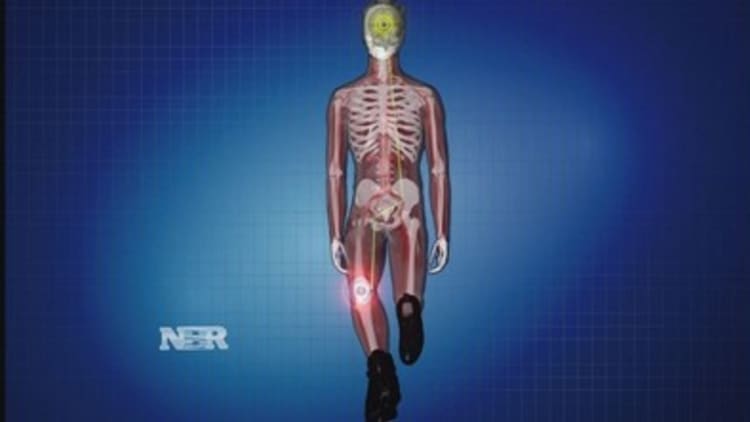

The boots have adjustable pods built into the soles that are calibrated to create a subtle imbalance when the patient walks in them, which puts their brains to work. The act of rebalancing trains the brain to re-position muscles, aiming to correct the patients' back, hip and knee alignment while walking. They say the treatment often reduces or eliminates the pain caused by arthritis and other joint issues (watch the animation below).

Walking in the boot for 30 minutes to a few hours a day can reduce the kind of pain that often leads to hip and knee replacement surgeries. It also helps post-op patients, accelerating rehabilitation. While most are skeptical at first, 50,000 patients in Israel, the U.K. and Singapore have used Apos.

Does it work? Of the 1,300 Apos patients surveyed In 2011 by Britain's largest leading health insurance provider, British United Provident Association, more than 80 percent reported some reduction in pain.

For 10 years, Apos has been opening its own clinics, but that idea proved daunting when Apos launched a couple of years ago in the United States. Instead, newly installed Global CEO Dr. David Levy is using a different business model. Now Apos is taking advantage of the existing infrastructure for physical therapy in the United States. They're training physical therapists, starting in the New York City area, to use the system.

Read MoreAfter years of research, where we stand on autism

Levy, a one-time primary care physician who led PricewaterhouseCoopers' global healthcare efforts, was among the skeptics when he first heard about Apos, but now he says the convenience of the treatment is what makes it unique, "People want things faster, better cheaper. They want choice control, customization, they want their thing when they want it and they don't want to go to a hospital, they want to be treated at home."

Currently, Apos is not covered by medical insurance in the United States and it can cost up to $6,000.

The price tag may seem hefty, but more than 1 million Americans have a hip or knee replaced each year, typically costing tens of thousands of dollars.

Apos will collect a fee from physical therapists for each patient that signs up.

David Lipetz, who has a physical therapy practice on Long Island, has been using the therapy and thinks the opportunity it presents to reduce the need for join replacement surgeries is revolutionary.

Read MoreObamacare: You (still) can't fix stupid

"It's a game changer. I mean, I think once everybody really understands it and gets past the skepticism, it's going to change the way we look at orthopedic conditions and conservative management," Lipetz says.

While the way the system works seems relatively simple, Lipetz explains that it's much more complex than meets the eye, "The misconception is that we're training, we're making the muscle stronger and that's really not what's happening. What's happening is that we're manipulating the central nervous system. That's something that up until now we were never really able to do well."

When Elbaz and Mor started, they were trying to reduce joint pain. What they are doing now is not just a prescription for pain relief, it might help solve some of what's ailing the health-care system.

"What we learned in med school was the medicine, OK? The arena that we play in is now much broader, it's health care," says Mor, "There is not enough money, not enough manpower, not enough beds to do procedures to all the people that are suffering. Things need to be changed, we need to take treatment out of the facilities."