It may seem a bit creepy at first blush, but when you take out a life insurance policy, you're actually placing a bet that you will die early.

You won't be around to collect your winnings of course, but your beneficiaries will, and the sooner you die, the more valuable the payout will be to them.

On the flipside, the insurance company is betting you will live a long and prosperous life. The longer you live, the more premiums you will pay, and the more money the company will take in.

Those life insurance bets have actually been around since ancient Rome. But much more recently, a system of side bets has sprung up, known as "life settlements" or "viaticals."

Let's say you've been paying your life insurance premiums for years. You're getting older, your health is declining, and you need money. A life settlement allows you to cash in your chips by selling your life insurance policy, receiving a settlement that is less than the benefit your beneficiaries would receive after you die.

You sell the policy to a middleman or broker who in turn sells it to an investor. The investor picks up your bet by taking over your premium payments. Then, when you die, the investor gets to pocket the difference between the money he has paid, and the death benefit paid by the insurance company.

Just like life insurance itself, life settlements can be beneficial, providing vital funds for people who are elderly or terminally ill, and tidy profits for investors. But life settlements are also the subject of a multiyear crackdown by federal and state regulators because of the enormous potential for abuse.

Stacking the Deck

In one of the most notorious cases, authorities said Mutual Benefits Corp. sold $1.2 billion worth of fraudulent life settlements to thousands of investors before the Securities and Exchange Commission shut the firm down in 2004. Thirteen people, including company founder Joel Steinger, have been convicted in the nationwide scam.

Mutual Benefits made its initial fortune in the 1990s at the height of the AIDS crisis, when HIV was considered a death sentence.

Among those who sold their life insurance policies to Mutual Benefits was Olympic diver Greg Louganis, who had been diagnosed as HIV-positive in 1988.

"I was 28 when I was diagnosed," he told CNBC's "American Greed." "I didn't think I'd see 30."

After Louganis publicly revealed his condition several years later, a Mutual Benefits subsidiary approached him to become a spokesman, and to buy his $500,000 life insurance policy.

"They gave me a great deal," he recalled. "I think they gave me maybe 50 or 60 percent of the policy. In my mind's eye I didn't know how long I had, so it was buying me some time."

But Louganis had also unwittingly become a tool for Mutual Benefits to recruit more victims in a growing fraud.

After medical advances allowed HIV patients including Louganis to not only survive but thrive, Mutual Benefits needed a new supply of life insurance policies to sell to investors.

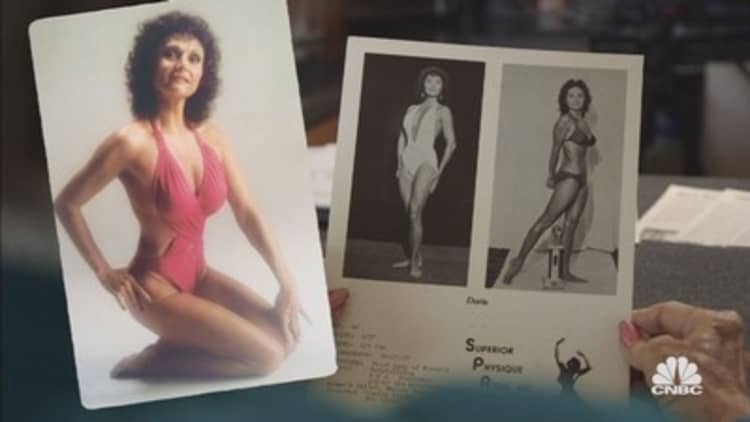

The company began to focus on buying and selling the policies of elderly people. But the demand from investors had grown so high that the company enlisted a crooked doctor — Clark Mitchell — to write fraudulent letters about the life expectancy of the policyholders, making the policies seem more valuable than they were. Mitchell is serving a 10-year prison sentence for fraud and conspiracy.

Ultimately, authorities say, Mutual Benefits became like a Ponzi scheme, selling artificially inflated policies to investors like Carol Tonzi, who says she has paid more than $100,000 — and counting — for the life insurance policy of a 95-year-old woman.

Tonzi says her accountant, who was also a Mutual Benefits sales agent, invested her in the policy without her knowledge. The problem? That 95-year-old woman just keeps refusing to die.

"I don't hope for her to die," Tonzi said. "But then when she does pass away, my nightmare will be over with. I will get my $102,000 and then hopefully retire."

Improving your odds

Still thinking of investing in a life settlement or cashing in your life insurance policy? Experts say be careful.

An entire industry has developed around persuading seniors to sell their life insurance policies rather than surrendering them or allowing them to lapse. It even has its own trade association, the Life Insurance Settlement Association (LISA), which notes that selling your policy can make good financial sense in many situations, including:

- Premiums are no longer affordable. A life settlement can provided needed cash—and eliminate a big expense—for people on fixed incomes.

- Insurance needs have changed. Family breadwinners often buy life insurance to provide income for their family in case the primary earner dies. But workers retire and children become independent, so a big life insurance policy may no longer be necessary.

- Term limits. A life settlement can provide a means to capture value from a term life insurance policy instead of just letting it lapse.

But even LISA acknowledges that life settlements are not for everyone. The transactions can have serious tax implications, for example, making it essential that you consult an impartial tax advisor. Depending on your particular insurance policy, there may be more cost-effective alternatives. Some policies allow you to collect a reduced death benefit while you are still alive. Others allow you to reduce your premiums in exchange for a lower death benefit. In other cases, you can borrow against the value of your policy. You may also be able to donate it to charity and claim a big tax deduction.

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners offers a list of additional tips if you are thinking of selling your policy. They include:

- Shop around. There are many life settlement providers. Make sure you are getting the best offer for your policy.

- Who gets the money? If you are on public assistance or are dealing with creditors, they may be able to claim some or all of your settlement. Make sure you understand all the implications.

- Guard your privacy. The life settlement provider is entitled to ask questions about your health from time to time in order to determine the value of your insurance policy. The provider is required to give you a written statement outlining who has access to your personal information. Read it carefully.

For investors, the Securities and Exchange Commission offers a long list of tips and warnings. They include:

- Seek unbiased advice. Make certain the financial professional you are dealing with won't receive a commission or other benefit from the transaction.

- Temper your expectations. The ultimate return on your investment is going to depend on how long the insured person lives. Remember the case of Carol Tonzi, who is still paying premiums for a 95-year-old woman? Life settlement brokers typically provide an estimate of the life expectancy of the insured; some even provide guarantees backed by bonds. But obviously no one can say for certain when a policyholder will die.

- Weigh privacy. Just as sellers may want to limit who can view their personal medical information, buyers understandably want to know as much as possible about the insurance policies they are investing in. Make certain you are comfortable with the information your broker provides.

For buyers and sellers, experts say be sure to check with regulators. Life settlement brokers typically must register with their state insurance commission or securities regulators. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners can connect you with the insurance regulator in your state. You can check out securities brokers through the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA)'s online Broker Check.

Life insurance — and life settlements — may be gambles, but that doesn't mean you can't improve your odds.

Watch "American Greed," Thursdays at 10p ET/PT on CNBC Prime.