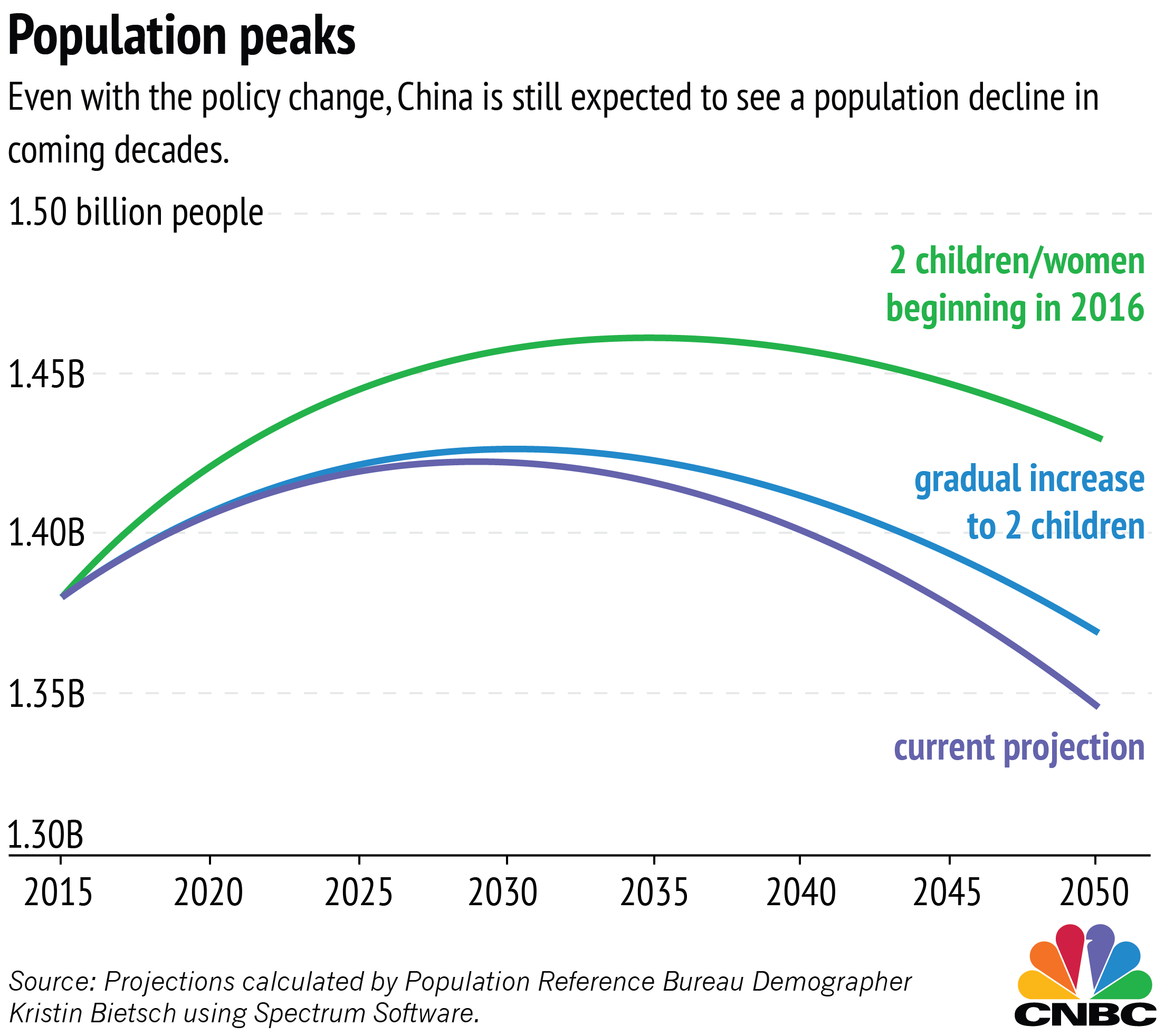

After more than 35 years of restricting many families to one child, China announced this week that citizens will be allowed to have two children.

Baby product companies like Biostime International and Goodbaby International saw their stocks shoot up Thursday. After all, there are 160 million women between the ages of 20 and 35 living in China — if they all went from the current average fertility of 1.7 children per woman to two children per woman over their lifetimes, that would be an additional 53 million children that wouldn't have existed before.

That may eventually help out diaper makers, but experts are skeptical that the move will produce a population boom or have much of an effect on the real problem: China's low fertility has created an imbalance between the generations, and working-age Chinese will soon be outnumbered by senior citizens.